Part 1

I recently finished Marcel Proust’s seven-volume novel In Search of Lost Time. As I read the last sentence, which appropriately ends with the word “Time,” (clever Proust, very clever) I felt a range of unexpected thoughts and emotions. I knew that I deserved the biggest cookie in the world. I also wanted a sign from the universe to acknowledge this labor of love, because I could be sure as shit that no one else in the world would really care about this personal accomplishment. I just wanted to brag and walk around the city, challenging people by saying, “Hey, I just finished the longest novel ever, what, do somethin!” though I realized that most people would laugh at my pretentiousness. So, instead, embracing the dorkiness of the endeavor, I write about my experience and will wait for the countless plaudits and emails to race my way. Here we go! (Disclaimer: If I sound a bit oh-look-at-me pretentious, please forgive me, I deserve something for this effort. LET ME HAVE THIS.)

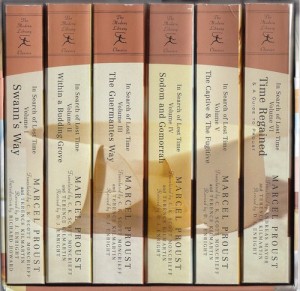

Some context/backdrop: Proust and his posthumous publishers split up his over 3,000 page novel into seven volumes. That comes out to over 1 million words, and if you’ve ever tried to read any of his volumes, you know the most prohibitive parts are the never ending sentences and paragraphs. You need to forget about that frequent reinforcement you get in reading that comes from the end of a sentence, paragraph or chapter. This in no way exists in Proust, and you need to give up any expectation of those consistent reinforcements that allow us to finish long literature. This takes time to get over, and I don’t know anyone who can say that the beginning of Proust was smooth or easy sailing. It takes time to learn how to read the book, though Proust will teach you the best way to read his writing, which is very nice of him.

I read this novel over a period of five months, from June to October, but I must mention that I attempted to read the first volume, Swann’s Way, at least twice before to little success. The first two times I made this endeavor, I actually grew to hate Proust. In my arrogance I thought that if I could not even get through one page, then the problem must lie in the author, not in me, the great reader. I soon realized that, attempting to read Proust, even at the age of 21, and then 23, I was neither mentally nor intellectually prepared. It requires some real high level discipline, patience, and even more patience. (If Proust gave me anything, and I would contend that he gave me a lot, he at least gave me a widened attention span. Now, I’ve moved on to reading all of Tolstoy and I find his large books breezy compared to Proust.)

For the first four volumes, I read the new Penguin translations, most famously Lydia Davis’s translation of Swann’s Way. Unfortunately, for whatever reason the last three volume’s of this translation effort only came out in Britain, and I did not feel like ordering them from England. Instead, I switched to the Modern Library translation. I didn’t notice any obvious differences in the translations, though a more perceptive reader might. The only difference between the versions arose in layout and aesthetics. The Penguin covers are gorgeous, and I love showcasing the first four in a set on my bookshelf. They just look great. However, the Modern Library’s layout, with less words on a page, made me feel considerably more accomplished. So choose your path if you choose to embark on this endeavor. I know this sounds petty, but when you find yourself in the world of Proust something as small as the beauty of the covers or the layout of page can matter immensely.

Before I try to describe some of my more serious thoughts and feelings about the book, let’s do some more direct and fun recap:

Best Title: In the Shadow of Young Girls in Bloom.

Best Line: “Must cancel plans, lies to follow.”

Best Book: Time Regained, Vol VII.

Favorite Character: Baron de Charlus.

Least Favorite Character Mlle. Verdurin

Least Favorite Book: The Fugitive.

Part 2

The experience of reading this book changed my conception of the novel. Proust cares little for the rules we learn in workshop. The book tells much more than it shows. Only about 10% of the book contains actual dialogue and the line between essay, fiction, meditations, philosophy, criticism on literature and art, and memoir blurs as to explode any definition of a novel. In these extreme conclusions I feel heartened by the sentiments of past greats. So many modernist authors described their awe, love and importantly, fear of reading or rereading Proust. Virginia Woolf worried that his influence would overshadow her own writing and would not read Proust while she wrote (“My great adventure is really Proust. Well — what remains to be written after that?”) Walter Benjamin expressed similar awe and concerns. I now understand this. Author after author worried that Proust all but made any further novelistic attempts obsolete.

The experience of reading this book changed my conception of the novel. Proust cares little for the rules we learn in workshop. The book tells much more than it shows. Only about 10% of the book contains actual dialogue and the line between essay, fiction, meditations, philosophy, criticism on literature and art, and memoir blurs as to explode any definition of a novel. In these extreme conclusions I feel heartened by the sentiments of past greats. So many modernist authors described their awe, love and importantly, fear of reading or rereading Proust. Virginia Woolf worried that his influence would overshadow her own writing and would not read Proust while she wrote (“My great adventure is really Proust. Well — what remains to be written after that?”) Walter Benjamin expressed similar awe and concerns. I now understand this. Author after author worried that Proust all but made any further novelistic attempts obsolete.

I know of little precedence for this innovative book. Even if we can find precursors in terms of his style and content, you will find nobody in his realm of ambition. More importantly, I can think of few precedents in their ability to succeed, to thrive, to create perhaps the greatest novel ever. I say that knowing full well that other people say that all the time, and knowing that this is not my favorite novel. I can think of many novels that speak to me on a more personal level. As much as I grew to love and understand 19th and 20th century snobbery and the intricacies of aristocratic life, I could only love it from a distance. As hard as I tried, I could not overcome the apparently unbridgeable chasm between our worlds. Of course we still live in a world of snobbery, of class, of money, of jealousy and love, but Proust’s world so differs from my own as if to feel at times alien. (Lionel Trilling, in his The Liberal Imagination, discusses these foundational differences). I accept that, but that creates a disconnect, and inability to fully connect unlike more contemporary novels like Infinite Jest or a myriad of other writers. Proust towers over everything now, but he does not obviate the need or urgency for the novel and writers, as other critics might have thought.

While I believe these small quibbles matter, they hardly can take away my unending awe, love, and respect for his accomplishment. It’s very hard to explain the level of excellency that he attains both on a sentence to sentence level, consistently throughout 3000+ pages, but also, and perhaps as impressive, how his vision coheres. He sets himself the goal of writing the book of life and succeeds. Nothing escapes his gaze, nothing escapes his pen. I cannot think of any other work of art, in any medium, that so captures the whole of life in as meaningful a way. More than other book I’ve read, you cannot separate the construction and creation of the book from the book itself. How Proust came to write this book matters, not only because he discusses that in the book itself. The novel is not only the story of his life, the story of French high culture, the story of sexuality in those times, but also the story of the creation of one of the best novels of all time. If this sounds meta, it is only in retelling. In the book itself it fits in seamlessly, and when, at the end, you arrive at the point in which the narrator finally decides to write his book, when desire and reality finally converge, this moment hits you exactly like one of the narrator’s involuntary memories (the madeleine episode signifying the most famous, though not most important of these instances.) At this instance, at this transcendence of time lost, you as the reader want to go back to the beginning to start again, as you rethink, reimagine, regain everything that came before.

On all writerly levels he will make you feel the way I tend to feel with Nabokov, as if, relative to them, I can only write with fat, broken crayons on construction paper. But, I believe, that this pervasive anxiety of influence also speaks to the unique power of Proust to overtake my life and thought. Once you adapt yourself to his world, it can take on immediacy and urgency, and even overtake the immediacy and urgency of your own world. He creates a world so shimmering with beauty as to make our own world feel stale, tired, and hackneyed. This isn’t simply a matter of his writing prowess, but the imaginative immediacy encapsulates the purpose of his whole artistic vision.

As he epiphanized in the last volume, Time Regained, Proust comes to understand that true life and beauty lie in our minds and imagination. The line between imagination and reality signifies a false binary opposition belies the fact that these realms bleed into each other at every second. In a sense reality only exists in our imagination and our imagination only takes form through reality. The truest form of reality is not what we experience, but in our malleable reactions our experiences. We all sense this on some intuitive level. We know that the both the anticipation to an event, and our exaggeration of its immensity afterwards, carry greater weight than the event itself. Reality, or what we call reality, let us down time and time again, but no such limitations exist in our minds. We tend to think that we work to ground ourselves in reality, but Proust sees this as a sort of resignation to inevitable sadness. Stay in your imagination to experience true beauty. Art is the only true consolation of life. Art, literature becomes less about reflection, about insight, and more of a chance for the redemptive actualization of our most lofty imaginative impulses:

Indeed the whole art of living is to make use of the individuals through whom we suffer as a step enabling us to draw nearer to the divine form which they reflect and thus joyously to people our life with divinities.

His ability to make, sustain, and concretize this counterintuitive argument speaks to his singular genius.

That Proust spent the last years of his life in a cork-lined room finishing his book not only represented the exigencies of his sickness, but signified heaven on earth to Proust. As much as he loved society life, he came to realize he could unchain himself from the horrors of physicality, the evilness of time through his unfettered imagination. That he consistently engenders this feeling in his readers speaks to both his insight and the power of his ambition.

Perhaps his greatest success, his greatest accomplishment and gift to literature is his ability to sustain the consciousness of one individual, himself, throughout the whole of life through the consciousness of one singular human being.

Part 3

The categorization of a book as a masterpiece creates a protective armor that defends against criticisms and pushes away prospective readers. We do well to not only laud but to criticize classics for their felt flaws, for their abiding humanity. Proust provides the reader endless material for frustration. So much of the book entails conversations and obsession over petty facts of society life, over who snubbed whom at which party while wearing what dress, with those shoes? That Proust speaks so much about this, page after page, forces the reader to begin to question where the adoration ends and satire begins. ( Imagine reading 20 dense pages about the minutiae of etiquette at a boring Parisian society party, or spending 30 pages on the shoe fashion of the day. Not a delightful task.)

There is also on display an abiding snark and meanness. The narrator will not flinch at cutting a person down to their most pathetic core, flaying their defenses, revealing them and all of us as the bottom feeders we are. There is a bit of grim playfulness in the extent to which the narrator loves to wrest back power or to burst any sort of self delusion in his cast of characters. This begins to display a sort of the whine of the powerless who sees the rich, beautiful, and famous around themselves with no ability to fight back but with biting insights. In this vein, Proust never flinches at passing judgment, superficial judgment, on large swathes of humanity. I still don’t understand Proust’s awkward treatment of his own homosexuality, or his apparent prejudice against homosexuality, against women, and his own clear snobbishness. That he will endlessly categorize and provide insight into people entails part of his appeal, but the manner in which he does so often sounds arrogant. His style verges on the didactic, even pedantic. He will often write about human nature, without qualifications, as if passing down received truths for the whole of humanity from his divine perch. Despite the literary tradition for this style, Proust’s use of it strikes me as particularly pretentious and short sighted.

The inverse of his frustration bordering on hatred for actual people is his lionization of beauty, of imagination. The downside of viewing art as the only true purpose and consolation to life is that a person begins to see all people as for aesthetic satisfaction. (At one point, the narrator laments WW1 solely because of the lack of beauty it provides to parisian culture. It’s utterly drab and boring for someone so obsessed with the pleasure of the beautiful.)

These frustrations and complaints, I believe, speak more to my personal predilections in novels. I tend to care more about ideas than about details. However, one of these frustrations blossomed into an opportunity to explore my own personal biases about life and living. Proust explains that “In reality every reader is, while he is reading, the reader of his own self. The writer’s work is merely a kind of optical instrument which he offers to the reader to enable him to discern what, without this book, he would perhaps never have perceived in himself.” While true, it is also true in negation, in what we find annoying and thereby exploring why we find this so annoying.

For me, I could not tolerate the narrator’s desire to give ceaseless time to air mundane grievances, reinforcing the general tone of narcissistic self-importance in all the characters. I could not tolerate 600 dense and knotty pages of one person delving to the depths of their jealousy. Why obsess over these utterly petty and stupid parts of the human experience. I know that we tend to say that these parts of the human experience make the grist for our novels, but read over 600 pages, almost in a row, about jealousy for one person, and you will begin to feel a bit weary, tired, emptied out of your concern on this matter.

This all changed when I began to think of my own relationships. I realized that the discomfort stemmed from my inability or lack of a desire to accept, comfortably, the shittier parts of my self. But what Proust argues for, both in content and style, both explicitly and implicitly, both in showing and telling is the importance of accepting, confronting, and loving the overwhelming power of our own involuntary memory, memories that do not distinguish between the moral or immoral, but sad or happy and between lofty of petty. I came to love the 600 pages devoted to jealousy when I experienced something all too similar. I realized that my annoyance stemmed from a desire not to accept this basic human vulnerability, from an insecurity about this type of obsessive and irrational jealousy thriving in each of us. I found myself more aware of my stupid jealousy and insane and incommensurate feelings towards a women. When I realized how adeptly Proust captured the range of my feelings, I dropped my judgmentalness and laughed. I laughed at my pretenses, at all of our pretenses in thinking we somehow can transcend this human pettiness. I wanted to thank Proust for this gift because the laugh that he gave me, in that moment, the laughter at myself freed me from emotional pain.

Part 4

Elaine Scarry, in her book, On Beauty, explains that when we encounter beauty we not only want to take hold of it, to keep it, but we instinctively desire to respond in kind. In this manner, his work demands at least a book-length response, but as with most masterpieces, the work itself serves as its own best commentary. Instead, a book about Proust would read much more as a sort of diary, a journal for reflection that uses Proust as a guide, an inspiration, a prod, and a source of beauty to explore your own world, your own reclamation of time. I do know that in the afterglow of his novels I see, think, and feel differently. I feel more mature even if this does not translate into action, and I laugh much more at that which I used to take seriously and take seriously that what I used to belittle. If books can change us then I feel changed, as to how, that remain uncertain. Time will tell me, I trust.

I leave Proust feeling lifted and lost, tired but invigorated, proud of myself for a five month achievement but knowing I barely skimmed the surface of this brilliant, frustrating, intolerable, endearing and pretty much every dialectic description possible. People tend to ask me if I recommend the book, as if you could give an easy answer to that question. In a sense, I could. No, I do not recommend this book. The book requires patience and devotion which normal people with real jobs cannot afford in their day. For those who want to devote this time to Proust, I feel certain that you too will sense some of his wizardry, and if you do, then let me know because I would love to discuss the book with you, with anyone really. I’ve gladly entered a small and dwindling world of people stupid enough to read this whole book and I don’t want to leave.

***

Tags: in search of lost time, Joe Winkler, Lydia Davis, proust, swann's way

wow, it took you only 5 months? way to go! like you, like so many others, i’ve tried swann’s way a bunch of times, only to become bored with page after page of parties and fashionable bitches. but you’re right–that boredom can teach you something. your review got me excited to try it again (prolly more like 5 years for me), and i appreciated your confession that it’s not the ‘greatest’ novel ever written. i’m down. i can’t wait. thanks for the motivation.

really nice treatment

No. I don’t care sir. I will not give you props for finishing a long ass book. I know you want it, but, no. I read a book because it will either help me understand things better, or assist in forming new creative sensibilities, or it’s just fucking good. Not out of some social obligation or for anything else that will, in the end, leave me with a feeling of needing to be congratulated on finishing a book. I don’t give a shit if the comment sounds negative or whatever the fuck. You finished a long ass book. Now go volunteer at a homeless shelter or something.

tell us how you really feel…

Wow, that was really good. I’ve only ever stumbled through the first few pages of Swann’s Way before giving up, but you’ve inspired me to try again – ideally on some kind of 5 month beach holiday.

I’ve read the first 2 and the last 3. I feel like I missed one. The Fugitive and Time Regained were my favorites. Feel like viewing Seeking Lost Time as a ‘novel’ is to misuse language. Seems more like a giant philosophical treatise. I think that Proust also isn’t inside ‘literature’ completely because he wasn’t well read in the classics. He was like Selby Jr., he was this person who read a lot of ‘normal books’ and for whatever reason wrote some weird shit.

I read Jean Santeuil also: that book was really boring. And it kind of shows that he wasn’t really into literature but like ‘drama.’

I feel like Seeking Lost Time is a giant Korean drama/soap opera.

Congrats on reading it :

Congratulations. My dad finished last year, and I hope to begin in the next year or two.

Nabokov wrote that the seven parts were “about a month’s reading, if you read four hours per day.” That’s two minutes per page, but hmmmmmmmmm

Also, are the Penguin translations much shorter? Amazon lists the complete Modern Library as 4211 pages.

[…] Joe Winkler tries to put Proust behind him. […]

It is interesting to ponder Tolstoy and Proust in relation to each other. War and Peace and In Search of Lost Time are the two novels which most consistently (and to this day simultaneously) earn the praise ‘greatest of all novels’. They are, as someone points out above, narrative arguments about history. Proust calls it time, with the aesthete’s emphasis on the personal, and this is the principal difference between them. Tolstoy was the great champion, or sentinel, of reality, and spent his whole life trying to disabuse people like Proust of their notions about style and ‘imagination’. His goal was to reconcile us to it, and to help us understand it. Proust’s message and Tolstoy’s message both have the funny and deeply earned implication that those who cannot transcend reality, or those who cannot approach reality, are cowardly and deserve what comes to them. The notion of a glory which accrued outside of an actual reality was not only offensive but deeply nonsensical to Tolstoy, whose understanding of human subjectivity was of such potency that it is either surprising or completely to be expected that he ultimately mistrusted its importance. Proust’s potency and understanding redirect from events and spaces any relevance they may or may not have. However, the ultimate arguments about history and time made by each of them require that they admit, in certain places, and in certain ways, that the other one is, after all, completely right.

NABOKOV WAS KIND OF A SHOWOFF BROOKS

LOVE THE GUY BUT YOU’RE RIGHT TO HMMMM

Great discussion. I made it through The Guermantes Way a few years ago then lost focus. This makes me want to pick it back up.

I think the reason the latter new translations aren’t in the U.S. is something to do with copyright. They will be available soon because the copyright is expiring, or something.

Seems like it did form new sensibilities for the reader

this is a terrible essay

so apparently not only am i too lazy to read ROTP, i’m also too lazy to read a review of it. i liked your first few paragraphs.

congratulations on the read – better you than me, bro

“Proust cares little for the rules we learn in workshop” might be the most absurd sentence ever written in English.