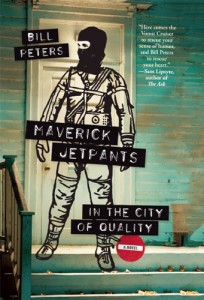

Maverick Jetpants in the City of Quality

Maverick Jetpants in the City of Quality

by Bill Peters

Black Balloon Publishing, October 2012

280 pages / $14 Buy from Amazon or Indiebound

Rebecca Solnit identified two disparate meanings of the word “lost” in her book A Field Guide to Getting Lost: “Losing things is about the familiar falling away, getting lost is about the unfamiliar appearing.” Bill Peters’ first novel, Maverick Jetpants in the City of Quality, does a tremendous job of exploring these two meanings with characters who think and speak with an idiomatic style made up of in-jokes (“Colonel Hellstache,” “Pinning Bow Ties on the Dead,” “Jaeger Cowpunch”) shared between characters that, over the course of the book, competes with the generic language of the Real World.

Peters’ characters ably resist the realities of adult life (until they can’t) and its pre-existing modes of expression, which one character claims have been “made stale or co-opted into oblivion by government agencies,” forcing man to be “incarcerated by his own linguistic detritus.” This helps to explain why, at an earlier point in the novel, that same character makes the following pronouncement: “Your dad was a gelding and your mother was a whale, and they gave birth to a suitcase with a flesh mask inside.”

The arc of Maverick Jetpants’ story will be familiar to readers of contemporary coming-of-age novels: Nate, the book’s narrator, chronicles the unraveling of his best friendship with Necro, an artist caught up in a “business opportunity venture” for “capital – you know – expenditure or whatever” with a dangerous group of neo-Nazis; the differences between his oddball stepdad (Fake Dad No. 3) and biological father (Real Dad); the banal thrill of cruising through a place (Rochester, New York, 1999) you simultaneously curse and celebrate; and the demands and dialect of adulthood.

Peters’ singular style is so good, though, his character’s sentence-shapes and sounds so far from bored or boring, that plot summary seems somewhat beside the point. Nate suffers from what you could call VDD (Vocational Deficit Disorder), and Peters’ voice sometimes resembles what Joshua Cohen recently referred to as E.S.L.: “Ennui as a Second Language, or Emulating Sam Lipsyte, a style that entertains through mortification, and mortifies through . . . you get it.” Even directionally challenged characters with bit parts have voices that want to sing on the page. A character introduced near the end of the book has the following first words: “So let’s go get that drink already […] Pitcher of Get-the-Hell-Outta-Here-Juice.”

As the novel progresses the constituent parts of Nate’s narration mutate from fast-and-furious slang to more serious units of straight-talk. Compare, for example, the following two passages. The first is from a scene early in the book, immediately after an explosion that has injured Nate and Necro’s friend Wicked College John; the second from a scene late in the book, involving their friend Toby:

“Because, I come out here and try to talk to Necro about a Plan. And, now? Necro knee-slides on the pavement to perform CPR on Wicked College John? Like he’s trying to be Tadahito Murakami: Ninja Surgeon and save the world?”

—

“Since I’m calling this evening over, I twirl my keys around my index finger. But suddenly I feel a scrape on my knuckle and my keys are gone, because Toby just yanked my key ring off my finger, hooked the girl’s body with one arm, and opened the driver’s side rear door and slammed it shut. He slaps down all the locks on the windowsills and immediately grabs the girl by her hair and facebombs her on the lips. I hear her gag and try to say something, and Toby’s suctioning her whole face practically, and something creaks in the car, and a handprint smears on the window, and I see Toby’s fist under the back of her shirt, and the girl’s hair mats up against the glass, and Toby almost rolls into the seat well, and the car shakes when he palms the floor….”

Notice the lowercase force of a word like “facebomb.” The idioglossia at the novel’s beginning seems to obfuscate as much as it reveals – Nate distances himself from the bewildering seriousness of Wicked College John’s pain by imagining Necro as Tadahito Murakami: Ninja Surgeon. But in the scene with Toby, Nate narrates each literal detail, creating in claustrophobic clauses the scene’s suspense.

Peters thanks Noy Holland and Sam Michel on his Acknowledgments page, noting that they “righted his brain, fiction-wise.” Holland and Michel both studied under Gordon Lish, whose righteous faith in the importance of sentence-level intensity seems an inspiration here. Also on his Acknowledgements page, Peters thanks Stanley Elkin, “whose story ‘A Poetics for Bullies’ I’ve been trying to write for years.” Elkin once stated in an interview that he always “begins with a vocation, because the vocation ultimately becomes a metaphor for whatever it is I find out I’m trying to say.” Conversely, but with similar syntactical pyrotechnics, Nate’s VDD – his lostness – fuels the metaphors Peters makes.

“A Poetics for Bullies” was referenced by Christine Schutt – another School of Lish alumna – in her “Books We Teach” interview at the Ploughshares blog: “In a long-ago class of mine at Nightingale-Bamford, the writer Amina Gautier first read Stanley Elkin’s ‘Poetics for Bullies.’ And as writers sometimes do, Gautier has since written a response to the Elkin story, which she read last summer at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference.” Maverick Jetpants in the City of Quality is Peters’ energetic novelistic response to not only Elkin’s story and style, but also the universal passage from adolescence to adulthood, the impermanence of friendship and familiar landscapes.

Rebecca Solnit’s new book, The Faraway Nearby, received a well-written review of the “not-enough-people-are-reading-this” variety. This sentiment seems especially true of Maverick Jetpants, which was published last year by the small press Black Balloon Publishing. The window of opportunity to escape a life unwanted, or, as one character puts it, find “somewhere where there’s maybe more of a demographic for us” is given vivid expression in Peters’ hands. Thrilling, too, is the narrator’s subtle transformation from someone who thinks of people as “walking bags of pain who have one or two chances ever to speak truthfully,” to a person who can imagine himself one day being “someone with taste for once, with a way of walking under banquet archways without smiling too much.” Readers looking for a story about the slippery transition from silliness to sincerity will find in Maverick Jetpants a style to savor and get lost in.

***

John Francisconi graduated from Emerson College in May with a BA in Film Production. He lives in New London, Connecticut. He wants to live in New York City.

Tags: Bill Peters, John Francisconi, Maverick Jetpants in the City of Quality

here, here! Read this in June. Fantastic book, and great review.