Microscripts

Microscripts

by Robert Walser

New Directions, 2010

160 pages / $25 Buy from Amazon

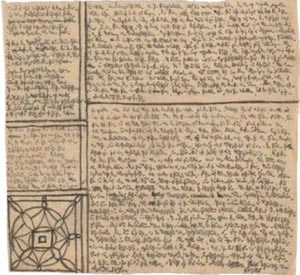

At their most definable, Robert Walser’s microscripts are meditations, essays, parables, and sometimes distillations of other authors’ works. Then there are more unclassifiable pieces; these are awkward journal entries, truncated portraits, and non-narrative stillnesses. In Microscripts, twenty-five of these handwritten miniatures appear in facsimile form with their English and German translations. Aside from their physical smallness, what the pieces have in common is a narrating voice that often pays self-conscious attention to its language. For Walser, words are a dangerous delight; they easily get away from him and can even embarrass him. Microscripts offers a tacit commentary on the author’s difficult relationship with language and writing, as well as an extension of his artistic project.

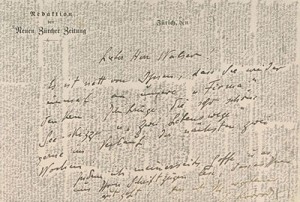

The microscripts are odd, and a reader ought to be curious about their origin. Walser wrote them in pencil using an outmoded German script called Kurrent, which was both esoteric and easily reduced to fit on small scraps of paper. Translator Susan Bernofsky’s introduction, “Secrets, Not Code,” offers several reasons for Walser’s turn to such an idiosyncratic technique. She says, “At first his literary executor, Carl Seelig, assumed that Walser had been writing secret code, a corollary of the schizophrenia with which he’d been diagnosed in 1929.” But a letter from Walser (quoted in Bernofsky’s introduction) discourages us from believing the microscripts are symptoms of his famous mental illness and institutionalization: In it he says plainly that he switched to his pencil-sketch method in order to “free himself from [a] pen malaise” that cramped his hand and stalled his creative activity. Bernofsky also tells us that Walser’s shift from calligraphic pen work to austere pencil roughs helped to ferry his ideas quickly from head to page. And finally, the method set up a protected writing environment: Kurrent in pencil was “unambitious, reassuringly safe,” because it precluded the scrutiny that Walser had once subjected his cursive to.

The microscripts are odd, and a reader ought to be curious about their origin. Walser wrote them in pencil using an outmoded German script called Kurrent, which was both esoteric and easily reduced to fit on small scraps of paper. Translator Susan Bernofsky’s introduction, “Secrets, Not Code,” offers several reasons for Walser’s turn to such an idiosyncratic technique. She says, “At first his literary executor, Carl Seelig, assumed that Walser had been writing secret code, a corollary of the schizophrenia with which he’d been diagnosed in 1929.” But a letter from Walser (quoted in Bernofsky’s introduction) discourages us from believing the microscripts are symptoms of his famous mental illness and institutionalization: In it he says plainly that he switched to his pencil-sketch method in order to “free himself from [a] pen malaise” that cramped his hand and stalled his creative activity. Bernofsky also tells us that Walser’s shift from calligraphic pen work to austere pencil roughs helped to ferry his ideas quickly from head to page. And finally, the method set up a protected writing environment: Kurrent in pencil was “unambitious, reassuringly safe,” because it precluded the scrutiny that Walser had once subjected his cursive to.

Regardless of Walser’s motivation for using the microscript tactic, what we have is a collection of material that may or may not have been meant for us to read. Bernofsky tells us that until their disinterment and translation, many of the microscript pages represented unsubmitted material and were:

Because the pieces are rough drafts, they beset us with the Will To Power question: Should they have been published? Rather than answer that question, Microscripts does us a realer favor, which is to leave it unacknowledged. The book doesn’t fully take for granted that the translations alone deserve our attention (to do so would be to rely only on our interest in Walser’s prose) but falls back on what the facsimiles lend to the story of Walser’s creative life. Indeed, Microscripts’ greatest performance is to make it impossible for the translations to have an existence independent of the original inscription surfaces and their biographical import.

Even if the facsimiles weren’t a particle of Walser’s own narrative, they would still be worth viewing. Microscripts looks like an exhibition book you might buy at an art museum after having seen the pieces themselves on the walls. Most of the facsimiles are double-sided, so we get to see both the scrawl and the indicators of what the remnant pages used to belong to (e.g., a calendar, a magazine, an envelope). Like Walser’s prose, they’re alternately gorgeous and plain, incomplete and over-complete, airy and busy, artifactual and banal. They also share with his prose an evasive quality. For those who can’t read his miniaturized Kurrent—and that’s probably most of us—it is a code, despite the title of Bernofsky’s introduction. Between the words and us, there’s an unavoidable abyss where meaning cannot be. And the paradox is this: Deliberately and sometimes severely arranged, the lines seem distended with a meaning that we’re meant to recognize but not know. Though the translations would be less intriguing without the facsimiles, we can easily take the latter up as discrete pieces of art. They give themselves to us as abstract reminders of our naturally strange relationship with language. They tell us that words—whether pedestrian or lyrical—demand that we invest them with meaning and place them in patterns, and are useless without our efforts.

Even if the facsimiles weren’t a particle of Walser’s own narrative, they would still be worth viewing. Microscripts looks like an exhibition book you might buy at an art museum after having seen the pieces themselves on the walls. Most of the facsimiles are double-sided, so we get to see both the scrawl and the indicators of what the remnant pages used to belong to (e.g., a calendar, a magazine, an envelope). Like Walser’s prose, they’re alternately gorgeous and plain, incomplete and over-complete, airy and busy, artifactual and banal. They also share with his prose an evasive quality. For those who can’t read his miniaturized Kurrent—and that’s probably most of us—it is a code, despite the title of Bernofsky’s introduction. Between the words and us, there’s an unavoidable abyss where meaning cannot be. And the paradox is this: Deliberately and sometimes severely arranged, the lines seem distended with a meaning that we’re meant to recognize but not know. Though the translations would be less intriguing without the facsimiles, we can easily take the latter up as discrete pieces of art. They give themselves to us as abstract reminders of our naturally strange relationship with language. They tell us that words—whether pedestrian or lyrical—demand that we invest them with meaning and place them in patterns, and are useless without our efforts.

And this is a problem that challenges and vitalizes Walser himself. He seems to want his sentences to have a blank and stable life without the demands of a semantic system. When I read the translations of stories like “The Songstress” and “The Demanding Fellow,” I see sober allegiance to scene as well as uncommonly generous descriptions, but like many of Walser’s short works, other pieces in Microscripts follow the caprices of association, which make appraisal difficult and final meaning improbable. One of the collection’s jewels, “New Year’s Page,” begins with these lines:

Meaning slips away; the words lose grip on all but the power of their images. And though the passage might evoke the Surrealist aesthetic, Walser’s language is not Breton’s. Nor is it direct, one-dimensional language that’s folded in on itself. It is penciled space, an architecture of words that would rather not be there in front of us. It’s direct only insofar as it foregrounds itself to establish a mutual queasiness. Walter Benjamin rightly says in his afterword, “Scarcely has [Walser] taken up his pen than he is overwhelmed by a mood of desperation. Everything seems to be on the verge of disaster; a torrent of words pours from him in which the only point of every sentence is to make the reader forget the previous one.” Benjamin might be referring prose like that of “New Year’s Piece,” or to the moments when Walser’s narrators reflect uneasily on what they’re telling. The narrator of the microscript titled “Journey to a Small Town” abruptly stops himself to say, “Seeing as this prose piece of mine is looking likely to prove respectable, that is, mediocre, I shall entrust myself to it.” The narrative here must go on in order to undo itself and its narrator.

Though Walser’s words aren’t comfortable with him or with each other, they find a form close enough to stability in the facsimiles. There they are satisfied because their enciphered hand nearly empties them of semantic freight. By housing the facsimiles, Microscripts enriches Walser’s language experiment—and this is its most significant contribution to his biography.

***

Jared Woodland is a graduate of the CalArts MFA Writing program. He lives in Los Angeles and is at work on a novel.

Tags: jared woodland, Microscripts, Robert Walser

–Knocking

I think Walser writes “words” that would rather “us” be right there in front of them.

His closet exhibitionism is, to me, thrilling.