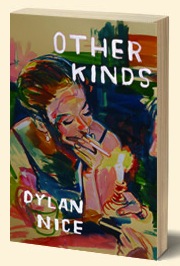

Other Kinds

Other Kinds

by Dylan Nice

Short Flight / Long Drive Books, Forthcoming October 2012

120 pages / $10.95 Buy from Short Flight/Long Drive

Dylan Nice’s first collection, Other Kinds, holds a particular resonance when placed alongside his recent essay over at The Rumpus [http://therumpus.net/2012/07/truth-in-nonfiction-a-testimonial/]. Each short story in this collection revolves around a young man who’s left his poor mountain home, but still doesn’t belong in the new land he has claimed. Most of the characters drove away from rural mining towns to the Midwest, or some other part of blank-faced suburbia. Now, the protagonist can’t return to where he came from—he’s too smart; he’s too quiet; his hands are too soft.

Nice writes in his Rumpus essay, “Truth in Nonfiction: A Testimonial,” about the Pennsylvania coal town that he came from: “I had spent much of my childhood in backwoods revival services, in evangelical youth groups, trips to praise and worship services in stadium-sized venues… I had come down out of the mountains with a wad of snuff in my lip and driving a high-mileage Ford.” This wonderful essay goes on to tell how books, in their slow and subtle way, brought to him an irrevocable change. “Other Kinds,” on the other hand, seems to tell of the price one pays for that kind of change.

The rural mountain landscape, a neighborhood where people “ate toast for supper and had no front door,” is the lonely background upon which these stories are set. The language it is written in—sparse, clean, clear as Appalachian spring water—is reflective of the no-nonsense, tobacco-chewing community that lays in the past. Again and again, we find that the main character simultaneously longs for and scorns the backwoods poverty that he was raised in. His failure to fit in in the new world—of universities and wealthy suburban towns—is often articulated in the context of women: women he wants, women who leave him disappointed. On the other hand, his rejection by the old world happens primarily in the context of men—the disappointed brother, the silent father. All of this loneliness is tempered with enough humor, though, that the reader never feels too weighed down.

For instance, in the excellent “Artifacts,” the narrator says, “I liked girls from money, but they wanted to dress me in polo shirts and take them to beaches with lifeguards on duty…I found things wrong though, things I couldn’t begin to address. She had a waterproof iPod player in her shower and plans to bear children by twenty-four.” The protagonists of these stories find themselves drawn to women who belong to a world that does not welcome them. In turn, the men in these stories are dismissive of the soft lives the women have been given. Compared with the poverty and harshness that they came from, nothing else seems quite real. This is articulated particularly well in the story “Wet Leaves,” which revolves around a man’s relationship with a young woman who goes to the Hallmark store just to look at the cards. Even though he’s left hardship back in the Alleghenies, the young man in the story still trusts hardship over sentiment: “She was soft and when I felt her I thought of words like ‘mild’ or ‘macaroni salad.’… My people were loggers and truck drivers—people who didn’t trust success as much as struggle.”

“Other Kinds” is separated into three sections, and each one is preceded by a very short epilogue. Epilogue I perhaps expresses the narrators’ attitude towards wealth best: “I did not like her house. I did not like its dry-wall. I did not like their hot tub, their dryer, their dishwasher. I did not like their lifestyle, their health. I did not like that I liked her…I wanted her to feel tired, cold, alone. I wanted her to be ashamed of everything she’d been given.” The tone never veers into a resentment of women in general, however—it’s just that confused anger of looking in on a party you weren’t invited to, but didn’t want to attend, anyway.

Only in the end of the last story, “Flat Land,” do we physically return to this homeland that has been constantly looming in the background. In a striking and beautiful turn, the narrator is expelled from his home in suburbia because of a housefire next door. He makes the long drive into the Alleghenies, to the company house of his brother Jason. Here, Nice masterfully shows the gut-deep affection that these characters still hold for the home they left, while simultaneously showing why they had to leave. It’s perfectly encapsulated in a lyrical passage about the character watching his baby nephew getting a bath in the kitchen sink:

“Her eyes moved slowly as her hands smoothed over the baby. A breeze blew over the house, sucking the curtain to the window screen and pulling trails of steam from the bath. I remembered winter baths as a boy: the open window, the uneven heat. I sat in the hot water in the old house with no other houses around it.”

But there is no place left for these characters in the world they’ve left. When the narrator in “Flat Land” goes to a neighbor’s house with Jason, Nice subtly renders the sense of expulsion that accompanies a coming of age—no violence, no anger, just a fumbling where things used to be easy. “Danny’s heavy wife came out and took their daughters into the house by the backs of their shirts. The blunt went around a few more times. There was nothing for me to be but a child. I didn’t know what to do with my face, where to look when I talked. They looked at me with hard fixed eyes. I was a thief. I was here because I could not pay for the things I needed.”

Above all, the thing that will make this collection carve a shelf for itself in your heart is Nice’s deft use of language. He has the rare and necessary gift of saying something that is simultaneously plain and expansive. He writes simple sentences with whole rooms behind them. The first passage that caught me in this way comes at the very beginning, in the story “Thin Enough to Break”: “We had gone to Our Lady of Grace that morning. I silenced myself before the silence. The kneelers hurt my knees. The Eucharist was blessed and families crawled over me through the pews on their way to receive it.” Much like the empty cornfield towns the characters frequently find themselves relocated to, it tells us something important and difficult to name, just by outlining a clear and lofty space.

This is a collection about the geography of home. How we leave it; how it does not leave us; how it becomes a space we can walk around in but never belong to again. It is imbued with a palpable longing to return to a place where we are no longer needed. It’s about the way we all want to return. We all want to be our parents’ children again, to walk in the front door, stamping our boots from the winter chill, and be embraced, be welcomed back. Above all, this book is about the dedication right there in the beginning of the book—it reads simply, “for home.”

***

Delaney Nolan’s fiction is forthcoming in Gargoyle, Guernica, Hobart, PANK, Post Road and elsewhere. Her chapbook “Louisiana Maps” (Ropewalk) will be published this winter. www.delaneynolan.com.

Tags: Delaney Nolan, Dylan Nice, Other Kinds

Is this book an example of “poorsploitation”?

I love how that cover jives with the cover of Big World. Sounds like a cool book, too.

it sounds great. can’t wait to check it out.

This is one of those books I’d buy just because I think the cover is really interesting. Now that I’ve read this I want to read it more.

I’m not familiar with that term, but I think I know what you mean, and the answer is no. The context of poverty is not used in a cheap or gimmicky way. It’s just the source; it’s where the speaker’s coming from, and it makes the stories all the more sincere. It’s a beautiful book. But don’t take my word for it! READING RAINBOWWW

We need more books and stories about working class people in rural America, since this demographic has fallen out of favor in publishing circles because of its association with the Republican party. I’ve noticed it myself: how stories set in rural America are often discriminated against by hip editors simply because the characters and region might conflict with the editors’ politics. I’ve kept track of the stats for my own stories set in the South, and the ones that use dialect, mention God or Jesus, and have characters who likely belong to the NRA are very difficult to place. Even if you disagree with those politics/beliefs, the point of fiction is tell the truth and be honest–to show the humanity in people you might not agree with in real life. The common rationalization to avoid stories about working class people in rural America, of course, is to call it “poorsploitation” (or other similar terms). I find that completely gutless.