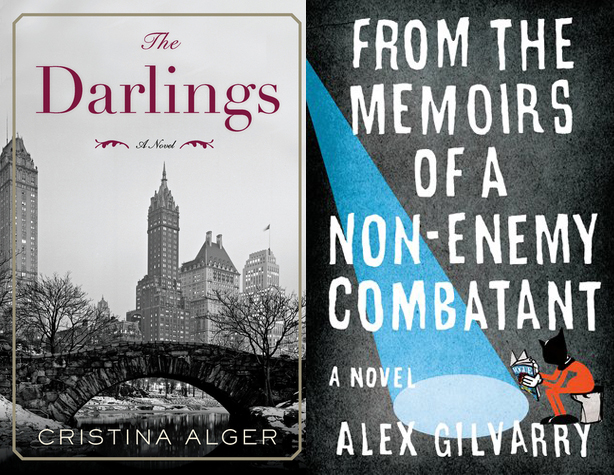

The Darlings

by Cristina Alger

Pamela Dorman Books, February 2012

352 pages / $26.95 Buy from Powell’s

From the Memoirs of a Non-Enemy Combatant

by Alex Gilvarry

Viking Adult, 2012

320 pages / $26.95 Buy from Powell’s

For the past couple months, Full Stop has invited writers like Justin Taylor, Alexander Chee, Danielle Evans, Maud Newton, and many others, to discuss the situation in American Writing. Most of the questions focus on the concerns contemporary writers face, particularly in terms of the responsibility, if any, writers have to respond to popular upheaval, social change, and the various crises our world is facing. It’s an important question–how do we write about the world we live in? The range of answers to these questions has been fascinating and they reveal the many differing opinions writers have about what we should be writing and what responsibility we have to document the world as it is changing.

I recently read two very different books, both responding to this world we live in, books that made me think about the different ways writers can approach the issues currently shaping our sociopolitical climate–The Darlings by Cristina Alger and From the Memoir of a Non-Enemy Combatant by Alex Gilvarry.

Cristina Alger’s The Darlings takes on the current economic crisis through the story of the Darling family—a wealthy clan of New Yorkers who find their lives irrevocably altered during a critical week when the family business is threatened by scandal. The Darlings, though largely enjoyable, is not a well written book. The overall narrative structure with chapters time and date stamped, is chaotic at best and hard to follow. The times don’t seem integral to the story and yet there they are as if this is the kind of novel where from one minute to the next important changes are taking place. The writing is more often florid than not, the descriptions overly ornate and clichéd, sometimes bordering on absurd–cheeks the color of peonies, raspberry lips, etc. Everyone is beautiful and thin. The women don’t eat and drink too much. The men work and philander. The Ivy Leagues and Eastern seaboard boarding schools are well represented. It’s all very Real Housewives: Bear Stearns and the Trust Fund Babies Who Love Them.

To remind us that this is a story about the follies of the 1%, there’s a lot of brand name dropping—Patek Philippe watches, Mercedes Benz cars, homes in the Hampton, glittery Park Avenue addresses. I am fairly certain this book was sponsored, in part, by Blackberry because the usage of the device is so prominent throughout the book, one can only assume there is a positive correlation between mentioning the device and financial remuneration. It’s certainly amusing to envision this rarefied world where money is or once was no object, and to consider how times are changing. At the beginning of the novel, for example, there is a charity event and alas, even on the charity circuit, they must take austerity measures, because, “no one wanted to see orchids at a five-hundred-dollar-a-plate charity event, not with the Dow hovering around 8,400.” Quelle tristesse.

Then there’s the plot. Carter Darling, the patriarch of the powerful Darling family, runs a hedge fund, Delphic. His sons-in-law Paul, married to Merrill Darling, the smart daughter, and Adrian, married to Lily, the socialte daughter, also work for the firm. When the head of investment firm that manages a significant portion of the fund’s assets allegedly commits suicide, it is quickly revealed that the firm was an elaborate Ponzi scheme. The sky is falling! There’s an SEC investigation, a son-in-law’s divided loyalties, an affair, an ex-girlfriend, a secretary who knows too much, a stoic matriarch, and all manner of subplots meant to keep us intrigued beyond the financial scandal. Once you get past the writing, The Darlings is a fun, gossipy read.

I don’t begrudge escapism, and there were mildly intriguing subplots that kept me turning the pages as fast as I could. (Who is the mistress? What will happen to the family? Who killed Laura Palmer?) At times, the breathless cataloging of the trappings of extreme wealth is a bit much. At one point, a mother, reflecting on her young disabled son, thinks, “the worst thing in the world for him, she knew, would be for his mother to act as if he were a cripple,” which, I assure you stands out uncomfortably because the term cripple has, for the most part, been banished from our vernacular. I certainly don’t believe in privileging political correction over art, but the word’s casual usage in a story set in the past couple years, makes you wonder how it got past an editor.

Alex Gilvarry’s From the Memoirs of a Non-Enemy Combatant takes on a different, but equally pressing issue—the erosion of civil liberties after 9/11 as part of the unchecked “war on terrorism.” Gilvarry uses the world we live in as a foundation but builds an imaginative story that goes beyond the headlines. Until I read this book, I could have never imagined that a novel about a fashion designer could offer an incisive look at the complex issues of civil liberties and government detainees. That’s the balance we have to find in using fiction as a vehicle for social commentary—negotiating the issue at hand and writing an entertaining, well-crafted story. Trying to achieve that balance is the struggle clearly at work in The Darlings. Gilvarry, in trying to balance social commentary and fiction, is much more successful.

Boyet Hernandez is a fledgling fashion designer from Manila. When he arrives in New York in 2002, the towers have fallen but Boyet, who goes by Boy, is all immigrant optimism, eager to find fame and fortune in the big city—”Sure, the financial skyscrapers, the sprawling bridges, the underground love tunnels, the people in their park-side penthouses—these were physical proof of the impossible. Manhattan was a testament to everything being out of God’s hands and within Man’s.” The novel is told as Boy’s memoir, written while he is held indefinitely and without charge at Guantanamo. The narrative goes back and forth between Boy’s incarceration and his years in New York. He is being held as a non-enemy combatant because his label was funded by Ahmed Qureshi, a suspected terrorist, and the federal government wants to know what Boy knows, which is little.

Throughout Boy’s memoir, we learn about the rise and fall of his fledgling fashion label, his personal entanglements, his appreciation for America and then his disillusion that is not strong enough to overcome his love for his adopted country. There are footnotes, throughout, by reporter Gil Johannesen, footnotes that often reveal Boy’s unreliability as a narrator and add a layer of complexity to an already complex story. As the novel unfolds, we see how Boy’s faith in the United States erodes, how he begins to lose hope he will ever be free—“Now that I approach the end of my confession, I find that I am beginning to lose hold of my character. I have become removed from the hero of my own story, you see. To lose hold of your own character must be park of the natural order of things in No Man’s Land.”

The novel is meticulously researched, both in terms of depicting Boy’s incarceration and in authenticity of the depiction of New York’s fashion scene. The writing is witty and fast-paced. Gilvarry is very adept at creating a well-developed protagonist who is charming in all his imperfections and his wide-eyed adoration of everything he is trying to achieve. The story has an interesting satirical bent that Gilvarry certainly could have pushed further, but overall, the novel is really compelling. Gilvarry’s works very successfully from his original premise. Even though this is fiction, the novel is also very affecting in how it portrays the injustice of unchecked judicial authority, affecting in ways that might not be possible in journalism. Sometimes, the best way to tell a story is by actually telling a story.

Toward the end of From the Memoirs of a Non-Enemy Combatant, Boy laments the play his ex-girlfriend Michelle has mounted about their relationship while he languishes in prison.

“My greatest fear to come of this recent development is that Michelle might actually have the influence to sway public opinion. That is the power of entertainment. Sure, when the government spins a story like mine, you will always have your believers, those dumb enough disciples who follow their leader no matter how much of a stuttering fool he is; but you can also count on a good many doubters, those citizens who question what is being force fed to them through the media test tube. And it is this group that I am worried about. For no one is immune to the force of good art when it is disseminated through the mass media. I know this better than anyone, for it is this foundational essence of the human condition to which I owe all my own success.”

When we try to use writing to respond to the world we live in. We are trying to use the power of good art in entertaining, engaging ways to create change or to create awareness or to make sure we do not forget the way the world is and was at its best and worst. We’re trying to write toward this foundational essence of the human condition to surrender to the force of good art. Sometimes we succeed; sometimes we do not.

Tags: Alex Gilvarry, Cristina Alger, The Situation in American Writing

im not leaving these comments till my vague demands are met and/or my bonus package goes through the finance dept.