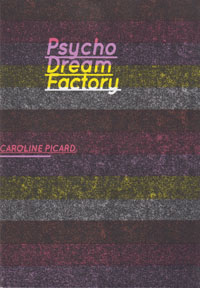

Psycho Dream Factory

Psycho Dream Factory

by Caroline Picard

holon press, 2011

111 pgs / $20 Buy from The Paper Cave

In line at the grocery store Shiloh perches in Angelina’s arms and Whitney Houston is dead. Celebrity eyelids: collated rainbows. All the flesh slick, like paper money.

Celebrity

millions upon millions upon millions of images of Marilyn

Monroe:

her absence.

Psycho Dream Factory sat in a prominent area of my home for most of winter so I could see it because it’s beautiful.

One page is a glossy, hot pink. On it, Mark Fisher, author of Capitalist Realism:

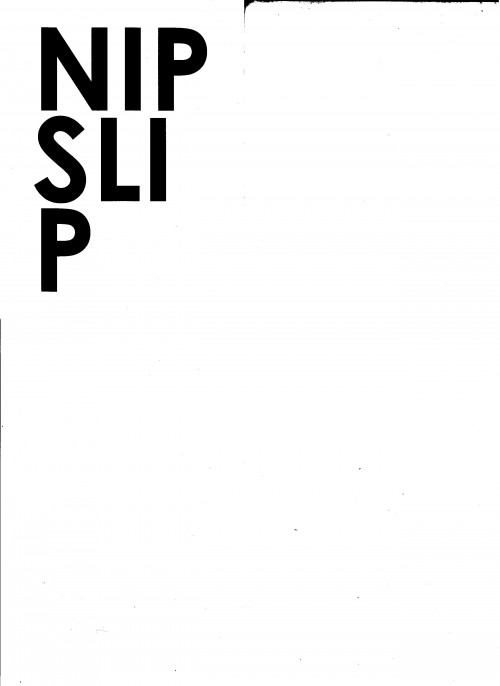

One morning in December I took the book off the table and brought it down to the floor. On my knees I opened it. A slip of paper tumbled out: white postcard bleating sleek, black, hyper-large:

I placed the notecard back in the book and returned it to its place on the table. January, February. I continued passing the book as I passed through my home, thinking about the notecard and the cover. In late March, I carried the book to my kitchen table, opened it:

I closed the book, turned to a page at random, saw:

Before the post-modern man could write the rape scene, he wrote about Penelope’s unweaving. He had to let himself undo himself before submitting to violence.

He sat at a desk in a train car apartment with a collared shirt. His sleeves rolled up. He wrote looking back. His hands shook with effort.

Penelope watched him from where she sat, in the past.

Psycho Dream Factory is a special size, larger than a standard paperback and smaller than a magazine. Static between expectations.

_____________

In celluloid there is always mourning, Lily Robert-Foley writes in her introduction to Caroline Picard’s 2011 release from Holon Press, an artist run imprint of Chicago-based Green Lantern Press. Picard and other artists founded the non-profit press, focused on bridging contemporary experience with historical form.

The first piece in Psycho Dream Factory, “P/oar : An Origin Story,” begins with Odysseus wandering the Mediterranean, placing women “in respect to himself”:

So long as he can marry Penelope, Odysseus agrees to assist in the finding of Helen a husband.

Odysseus awards Helen to Agamemnon; everyone claps.

Odysseus slits the belly of a horse, entrails “later, a prophet would examine.”

Odysseus watches the organs spill to the ground, a sign of the suitors’ virtue.

“P/oar” then cuts to the famous patient, “HD, (formerly Hilda Dolittle),” stomach-cramped before a silent Freud, speaking unrelated phrases from the examining couch.

Later, a post-modern man appears. Tacked beside his desk is a photograph of Marilyn Monroe. Her waxy eyes watch him write a novel he will never finish:

The Spartans never lost a war some say because they were a democracy some say because they were warriors some say because they had nothing to steal—

they preferred to eat dry bread and drink water and go shoeless and wear burlap—some say they never lost a war because they never thought of anything as anyone’s own some say—

They got something with Helen.

Return to HD and Freud, on the way to Greece in a passenger boat, where she tells him:

And then:

_____._____.______.

Helen drugged the man as she’d beaten the goat.

Repossessed after the way, she had returned a quiet woman with sleeping potions.

Next, the story’s last paragraph, where letters go missing:

Words crack the page and spill spatial, grammatical yolk. Penelope, in her linguistic incoherence, wanders her own eccentric route at last, absent of husband Odysseus. Emptying of letters, the words on the page go gap, fissure, dysjunct.

Psycho Dream Factory opens into eleven more stories. About Woody Allen, Soon-Yi. Charles Darwin‟s turtle, Harriet. Yoko Ono. The e-bay woman who sells serums of her DNA. Dre. James Franco. More mythology. Bolkonsky and Russian soldiers of 1812.

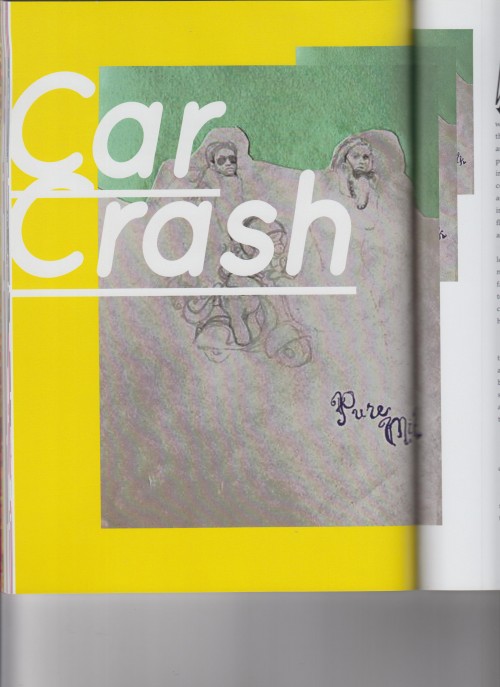

In “Car Crash,” “time occurred out of synch.” A young boy’s last smells are both bodily and consumer: merge of earth-shit with leather-air freshener.

Art and life bleed in these stories in the way celebrity culture reflects contemporary art.

Picard invokes this mirroring at the end of Psycho Dream Factory, in a Coda. It is here that a story like “P/oar” gongs beside a piece like “Human Furniture,” where celebrity icon Bruno, unemployed “in the aftermath of his film,” is compared to “American Apparel starlets who submit to the photographic gaze of The Boss.”

Picard calls for a new way of contextualizing the current celebrity system:

Picard invokes Maya Deren’s The Divine Horsemen, a film in which “the action of addition indelibly transforms the original units.”

Picard knows our participation in contemporary culture is inevitable. We can all relate to the celebrity desire for success and recognition, and their provocative promises of permanence and stability.

Deren’s additive principle provides a strategy to satiate the narcissistic playground of celebrity in which we are all entrenched, beside our tabloid headlines and candy bars and humming fridges of Vitamin Water.

Like the historically transcendent pieces in Psycho Dream Factory, we might live in this “veneer of cultural product and dissemination” in a way that deprives it of its consumptive power by performing our own work of flattening. By perceiving the cracked-ing surface of celebrity, the constant flux becomes static-transcendent.

Perhaps then the key lies in focusing our attention elsewhere: studying the blurred, interstitiary matter between categorical selves.

Picard concludes with a call for a “robust and generally uncelebrated life—not the wizened fool sitting by the river, but a modest cousin who bakes bread for family and friends.”

And so we might glean a fissure in the pervasive cloak of the image factory haunting us in grocery lines and on billboards, this “illusion that something, or someone, can be simplified and projected onto a surface.” In recognizing these dangerous illusions, Picard calls for an interstitial transcendence. Surfaces without depth, empty of consequence or complexity, we might see a partial self. A self to be supplemented. “A new means to measure success.”

***

Tags: August Evans, caroline picard, Psycho Dream Factory

August! Caroline!

this is great, thanx

AD!

[…] can read the rest of the review by going here Posted in Art, Caroline Picard, Fiction, Holon | Tagged August Evans, caroline picard, Holon […]