Where Art Belongs

Where Art Belongs

by Chris Kraus

Semiotexte, 2011

160 Pages / $13 Buy from MIT Press

&

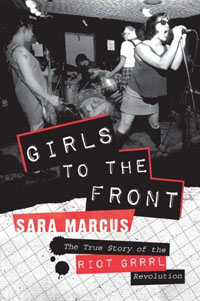

Girls to the Front

by Sara Marcus

Harper Perennial, 2010

384 Pages / $15 Buy from Amazon

If you’re invested in the lives and work of girls as cultural agents, then you’ll like Sara Marcus’ Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution and Chris Kraus’ Where Art Belongs. Like certain of my punk obsessed friends, my interest in bands like Bikini Kill and Bratmobile developed in high school during the late 90s. And by then the whole riot grrrl phenomenon in its original incarnation, with Kathleen Hanna front and center at the mic, was more or less dead. By the time I was introduced to Bikini Kill’s first album, the band had already released its final album Reject All American and played its final show in April 1997. Subsequent fans were left to speculate on both the political origins of the band and the interpersonal relationships that constituted riot grrrl as a living, breathing feminism.

After more than a decade of piecing together the fragmented narrative through punk-inspired zines and sporadic interviews given by devotees, I am happy to report that we finally have a proper history of riot grrrl that can more or less serve as a sourcebook for both curious outsiders and knowledgeable insiders. Of course, the problem with many texts on the history of punk music is the degree to which certain authors tend to overestimate the influence and importance of theory, both on the development of punk and its relation to other para-utopian currents. Academic texts like Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979) and Dave W.’s The End of Music (1978) have a tendency to highlight and play up the avant-garde connections that bands like The Sex Pistols had to situationist theory, while simultaneously downplaying or totally ignoring the belligerent and non-intellectual origins of punk. As the underground music historian Stewart Home points out it in his text The Assault on Culture:

When encountering any history on riot grrrl, perhaps my biggest apprehension is that the significant events and key players will invariably be disavowed and displaced by the solipsistic insertion of French theory via Deleuze & Guattari, Derrida, and Foucault. Initially, so the story goes, Kathleen Hanna started a band because her literary idol Kathy Acker told Kathleen that she should be in a band. After reading a copy of Blood and Guts in High School from one of her photo teachers, Hanna enrolled in a workshop in Seattle led by Kathy Acker. There Acker advised her to reconsider her artistic direction: “If you want people to hear what you’re doing, don’t do spoken word, because nobody likes spoken word, nobody goes to spoken word. There’s more of a community for musicians than for writers. You should be in a band.”

Given the fact that early in Kathy Acker’s writing career she was involved with mail art and partially subsidized by Sol Lewitt, it would be easy enough, for a Dick Hebdige, to construct a tradition running from Futurism and Dada, then via Surrealism into Lettrisme, Situationists, Fluxus, Mail Art, Punk, and Riot Grrrl. An unscrupulous intellectual might even be tempted to use the fact that Acker dated Sylvere Lotringer, the founder of Semiotexte who introduced French theory to the states, to weave a narrative of riot grrrl as the confirmation of the tenets of high theory. Thankfully Girls to the Front avoids such philosophical dead ends and deals primarily with significant riot grrrl events and principal players; from the do-it-yourself sensibility in Olympia’s Evergreen, an experimental state school, to the fall 1989 semester at the University of Oregon – Marcus does an admirable job of detailing the birth of a scene that prioritized the myriad possibilities of girls just beginning to find their sense of agency in the world.

A similar admiration for emergent cultural agents can be detected in Chris Kraus’ Where Art Belongs. A collection of essays divided into four parts (No More Utopias, Body Not Apart, Matrix, and Drift) Kraus does an ideal job of capturing the excitement during the early stages of Tiny Creatures, an alternative arts space at the edge of Echo Park near downtown Los Angeles. Similar to how a handful of girls in the Northwest were responsible for igniting a new music scene, when Tiny Creatures took off it was because of the resourcefulness of certain key individuals:

A similar admiration for emergent cultural agents can be detected in Chris Kraus’ Where Art Belongs. A collection of essays divided into four parts (No More Utopias, Body Not Apart, Matrix, and Drift) Kraus does an ideal job of capturing the excitement during the early stages of Tiny Creatures, an alternative arts space at the edge of Echo Park near downtown Los Angeles. Similar to how a handful of girls in the Northwest were responsible for igniting a new music scene, when Tiny Creatures took off it was because of the resourcefulness of certain key individuals:

Like Kathleen Hanna’s contribution to Bikini Kill, it is impossible to see how Tiny Creatures could’ve survived without the vision and commitment of Janet Kim. As Kraus points out, it was Janet who maxed out all of her credit cards. It was Janet and her partner who founded an indie label called Tiny Creatures to record the music of LA bands. It was Janet who organized the first gallery show of visual art by Ariel Pink and Andrew Arduini. And it was Janet who acted as the dutiful archivist with hundreds of photos of Tiny Creatures events stored away on her desktop. Given Kraus’ affinity for Dick Hebdige and Sylvere Lotringer, it would’ve been easy to excuse Kraus had she overlooked Janet Kim’s work in favor of a more theoretical approach to LA’s subculture. Luckily for us, Kraus sticks to the facts even when those facts seem to contradict the explicit aims of Tiny Creatures:

It was in this climate that Kim produced her first Manifesto. “Tiny Creatures is not a gallery . . . is not a venue . . . a label . . . Tiny Creatures is a community center . . . glorifies expression and communication, not the ego . . . Tiny Creatures is not to be used to commodify art or music, but . . . as an instrument of communication.”

Not unlike many para-utopian collectives born out of youthful optimism and idealism, the concatenation of art and activism has a tendency to attract its share of jerks and assholes. For both Kraus and Marcus, the degree of intellectual honesty with which they write about their subject matters from a warts-and-all position is instructive, especially for those of us who may be toying around with the act of documenting and writing about our own local fringe. Throughout Where Art Belongs and Girls to the Front both authors generously assumes that the reader understands that while the cultural projects they are writing about situated themselves in opposition to America’s celebrity culture and consumer capitalism, they also emerged out of consumer societies based on such modes of ideology and thus do not entirely escape the logic of celebrity.

This is obvious in Chris Kraus’ account of how certain Tiny Creatures’ artists, like Jason Yates, began to expect professionalism and more monetary rewards from Janet Kim as the group received more and more outside Artforum-adjacent attention. This is particularly obvious in Sara Marcus’ portrayal of the writer and musician Jessica Hopper. Prior to reading Marcus’ book, my primary impression of Hopper came from the now-defunct Punk Planet Magazine. In her monthly columns Jessica always came off as entirely committed to the cause, emphatically considerate of her peers. However, after reading Marcus’ account, one gets a totally different picture of Jessica during her pre-Punk Planet days:

[When] Bikini Kill came through Minneapolis . . . [t]he members of Bikini Kill now struck Jessica as curt and selfish: eating all the food in the house, making a lengthy long-distance phone call and not offering to reimburse her friend, . . . presumptuously demanding extra freebies. “They were my teenage icons – I didn’t think about them as being human people,” Jessica said. “I was totally put off. . . . I let go of some of the idea of Riot Grrrl right then. I thought, these people are just as fake as anybody.”

This leads us back to the starting point of the antagonistic relationship between the belligerent non-intellectual origins of art activist practices and the pseudo-intellectual academic texts that obfuscates and mystifies creative social transformations. The lesson here is not that Bikini Kill and Tiny Creatures failed in their emancipatory pursuits, nor that they failed to live up to the radical concatenation of art and revolution. As Chris Kraus points out in her epilogue, “There’s no such thing as a failed utopian community; or, if the collective is an experiment in shared time, how can time fail? A great sense of failure couches every success.” This is Kraus at her Beckettian best, echoing the line from Worstward Ho: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” The fact that Tiny Creatures participants were imperfect and flawed is no excuse not to begin from the beginning once more; nor does the fact that Bikini Kill wasn’t able to sow the seeds of a punk feminist nation-state run exclusively by women an excuse to abandon the cause. As Sara Marcus reminds us in her epilogue, “People grew out of Riot Grrrl, but that doesn’t diminish the movement’s value, . . . Riot Grrrl, by encouraging girls to turn their anger outward, taught a crucial lesson: Always ask, Is there something wrong not with me but with the world at large? It also forced us to confront a second question: Once we’ve found our rage, where do we go from there?”

Today, perhaps more than ever, these dual questions about the world at large and its transgression appear to be effectively disavowed, or at the very least marginalized, by our institutions of higher learning. Marcus, who received her master’s from Columbia University, and Kraus, who teaches at various art schools, are two of the few para-academics who have looked at riot grrrl and LA’s beaubourgs without resorting to scholarly pyrotechnics. Bring up Bikini Kill or Tiny Creatures to your on-campus Marxist and you’re bound to be greeted with a yawn and called naïve. I recently made the mistake of introducing the twin topic to a self-described “dialectical thinker” and his reaction was unsurprisingly lazy: When we disobey the Law, we do so as part of a desperate strategy to affirm the Law; so the more rigorously we disobey the Law, the more we bear witness to the fact that, deep within ourselves, we feel the desire to indulge the Law. Following this well-rehearsed line of superego dialectics, I am to conclude that the cultural activities of Kathleen Hanna and Janet Kim are futile, self-defeating, and ultimately without worth or significant value. If by chance you find yourself seduced by such rhetorical special effects, or perhaps in the past you bought into a similar Baudrillard-inspired nihilism, I implore you to take a look at Where Art Belongs and Girls to the Front. Afterwards you might just find yourself starting your own scene with your friends, rooted in the particulars of your own life and what gets you fired up.

***

Maxi Kim is a co-founder of Beaubourg 268.

Tags: chris kraus, Maxi Kim, riot grrrl, Sara Marcus, Semiotext(e), where art belongs

Dead on.

tinyurl.com/4skyaqr

[…] Kim has written a fantastic review of Chris Kraus’s Where Art Belongs over at HTMLGIANT. Maxi’s double-review (which also […]