In order to talk about a book I am certain will make many of the “best” lists this year, and one I loved, I’m also going to need to talk about three things I really hate in novels–epigraphs, prefaces or prologues, and epilogues.

When I read an epigraph or a series of epigraphs in the front matter of a novel, or even worse, at the beginning of a short story or poem, I then spend an unfortunate amount of my reading time trying to make sense of the importance of that epigraph. Is the epigraph a commentary on the writing or the story to be told? Is the epigraph a commentary on the writer or the reader? For better or worse, the use of an epigraph shapes and informs how we read the story that follows. There is an implication by the epigraph’s very existence, that the story cannot exist without the imprimatur of the wise or witty words of someone else. I never find the relevance of an epigraph no matter how hard I try. Epigraphs seem to be an indulgence on the part of the writer. Sometimes I read epigraphs and think, “Well, now you’re just showing off how well read you are,” particularly when the epigraph comes from some obscure text perhaps three people have read. I am even more vexed by biblical epigraphs. It makes me wonder if there is some spiritual agenda to the book I’m about to read and if I don’t quite understand the biblical verse I begin to wonder about the disposition of my immortal soul. It is all very stressful.

I am equally troubled by prefaces. When I see the word “preface” or “prologue” my natural inclination is to assume that the writer feels there is a need to sit down and have a chat with me before I read their book. With a preface, the implication is that there are a set of rules you need to make sense of before you can fully appreciate the writing to follow. If I really want to read a book and I see that there’s a preface, I simply pretend that the preface is what it should be–Chapter 1. While there are many arguments that can be made in favor of a preface, I would like to argue, vehemently, against the use of prefaces. I do not understand why, after a writer has written an entire book, they feel the need to backpedal and tell the reader, “Wait, before you get started, there are some things I need you to know.” As a reader, I want those “things I need to know,” to be built into the narrative. Don’t tell me a story before you tell me your story. Simply tell me your story. I have a bit more tolerance for an epilogue because, in a really good book, I don’t want the story to end. I want to know what happens next. I want to know about the story beyond the story, but epilogues can be troubling too, because at times, they give the impression of a writer who is unable to bring a work to it’s right and proper conclusion.

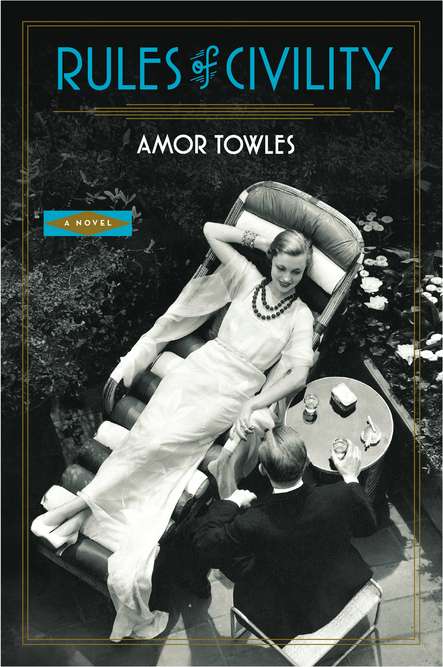

I share these strangely passionate opinions on epigraphs and prefaces/prologues/epilogues because Rules of Civility by Amor Towles, out in July from Viking, has a trifecta of elements I hate in books—an epigraph, a preface, and an epilogue. I was instantly concerned and predisposed to hating the book on principle. Upon finishing the book I am even more convinced I am right about epigraphs, prefaces, and epilogues, because this book did not need those elements to succeed.

The great news, though, is that despite these elements, Rules of Civility is a gorgeous, gorgeous must-read book that is an engaging story and a love letter to New York and writing about New York, just before the mid-century. The writing reflects the writer’s meticulous understanding of the tradition of writing preceding him, particularly the work of Fitzgerald and my beloved Edith Wharton. As I read the book I often thought, “This writer is a man who has read The Age of Innocence.” There is a dense, cinematic quality to the writing in Rules of Civility. No detail of life in New York City during the late 1930s is overlooked. From the first page, the reader is taken on a gin and champagne-soaked tour of Manhattan through the eyes of a Brighton Beach girl, Katey Kontent, who is making her way in the big city and reaching, reaching for something grander than New York society would otherwise allow her to have.

Katey Kontent is one of the most interesting female characters I’ve read in a long time and I give real credit to Towles for bringing this character to life in the way that he did. Kontent is smart, both pragmatic and somewhat of a dreamer, unabashed, witty, always able to come up with a clever retort. She never expresses any shame over her working class, immigrant upbringing in Brighton Beach, nor does she demonstrate any sort of mealy-mouthed deference to her social “betters.” That, ultimately, is the source of this character’s and the book’s immense charm.

Rules of Civility tells the story of Katey and her best friend Eve who meet New York banker Tinker Grey, at a jazz club on New Years Eve (“How the WASPs loved to nickname their children after the workaday trades: Tinker. Cooper. Smithy. Maybe it was to hearken back to their seventeenth-century New England bootstraps–the manual trades that had made them stalwart and humble and virtuous in the eyes of their Lord. Or maybe it was just a way of politely understating their predestination to having it all.”). The three immediately hit it off, both Katey and Eve vying for Tinker’s attention and affection so that they might someday leave the boarding house where they share a room and their jobs as legal secretaries. There’s an accident and Eve is seriously injured. Wracked with guilt, Tinker invites Eve to move in with him even though it’s clear he holds the most affection for Katey. Before long Eve and Tinker are in a relationship, Katey has moved into an apartment on her own, and the novel follows the next year of their lives, mostly Katey’s as she makes friends with the upper class and begins to move in their circles, and eventually becomes an editorial assistant for a new magazine, Gotham, about to debut under the leadership of a demanding, engagingly tyrannical editor. In the end, Katey learns that Tinker both is and is not the man she thought him to be and along the way meets what is so often referred to as a “colorful cast of characters,” who teach her all manner of things about life and love, wealth and status.

The story being told in Rules of Civility is simple and one that has been told before but what really elevates this book is the manner in which the story is told. The writing is richly descriptive, almost lush, and Towles has crafted sentences that demonstrate genuine care for the building blocks of a great novel. The book never gives in unduly to emotion. There is plenty of drama but the story is never weakened by unnecessary dramatics. After Tinker and Katey share a kiss, just before he and Eve become a couple, there is this moment: “I freed my hands and put a palm on the smooth skin of his cheek, taking comfort in the well-counseled patience for that which bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, and most importantly endures them.” It is a quiet, lovely moment and the bittersweetness of it really comes through.There are many such moments throughout the novel.

Later in the novel, Katey runs into Anne Grandin, who has been introduced as Tinker’s godmother, a wealthy society woman, and when Katey asks if Grandin disapproves of Tinker and Eve’s relationship, Grandin says, “Certainly not in the Victorian sense. I have no illusions about the liberties of our times. In fact, if pressed I would celebrate most of them.” The sophistication and wit of these characters almost threatens to feel unbelievable but Towles manages to exercise nice control over the libertine natures of his characters and the unapologetic ways in which they indulge themselves and those around them.

Often times, Katey Kontent’s wry observations take on the quality of aphorisms. When discussing one of her co-workers, a Charlotte Sykes who can type 100 words a minute, Kate observes, “be careful when choosing what you’re proud of–because the world has every intention of using it against you.”

I could probably quote nearly every line in this book as one that is memorable or beautiful or smart. The only misstep (other than the unholy trifecta) was the three or four sections where the novel shifts from Katey as the protagonist to Tinker Grey as the protagonist. These sections are very brief, and if they were not included, they would not be missed which means they are not necessary. That said, as a debut novel, Rules of Civility is a real wonder and I’m excited to read it again, and again. Rules of Civility was a real surprise and I took great pleasure in seeing a modern novel do something fresh with a style of writing we often assume has fallen by the wayside. Edith Wharton would be proud.

But alas, we return to this matter of epigraphs, prefaces and epilogues. I remain baffled as to why these elements are included in this novel. The epigraph is a biblical verse that is, indeed, poetic but does it enrich the novel in any way? Does it really inform the novel in some way? Absolutely not. The narrative frame established in the preface, presents Katey as a much older woman, attending a photography exhibit with her husband where she sees two photos of Tinker Grey taken a year apart, and then, suddenly, we’re taken back in time. I cannot help but feel that this is a cheap, cheap introduction into the novel, and it is a real disservice to a novel this exceptionally good. At the end of the novel, the epilogue catches us up on everything that happened to the most significant people Katey encountered during the year of her life this novel details and then returns us to the present with Katey back in her apartment with her husband in bed as she stands on her balcony reflecting on her history. I did not mind learning what happened to the characters to whom I had grown attached but to be jarringly thrust back into the present and to cheapen the beauty of this novel by framing it as wistful nostalgia is a creative choice that’s going to trouble me for some time.

Tags: Amor Towles, Edith Wharton, Rules of Civility

high school book report

Grade school comment.

I like epigraphs. I like them because they prepare me to accept mystery. Which is something I like in fiction; in fact, art in general. The epigraph reminds me that a book is part of the larger universe of words, of literature. I read an epigraph, and then proceed. Yet I don’t keep it beside me like a map a I move forward into a fictional world. I certainly never allow my reading pleasure to be distracted by an epigraph.

(The prevalence of Biblical quotes in books written in English should surprise no one.)

I believe people who find epigraphs distracting simply pay them too much attention. Surely, an epigraph is easily ignored. On the other hand, might it not just as easily be enjoyed? The obscurer the epigraph the better, in my view. Why quote what everyone has read before? The epigraph has often struck me as akin to a fanfare, a reminder that solemnity or attentiveness is now required as something is about to happen, a revelation, an unfolding fiction. Of course, not all works of fiction warrant an epigraph.

The absent epigraph isn’t anything at all, to some books, not even a ghostly remnant

of an abandoned form.

I like epigraphs too, but short ones. The Book of Daniel (Doctorow), for instance, doesn’t need that whole page of them. William Gay’s are good. The short ones in Butler’s new book work pretty well before the chapters, I think. If you are intimately familiar with what is being quoted they will put you in a state of mind that the author would prefer you be in before entering the work proper. That’s how I see them, I guess. A sort of overture that tenderizes the meat a bit. But, as I said, without familiarity with what is being quoted, they are useless, until you have finished the book and gone back to them.

I’ve never thought of epigraphs like that, as a reminder of the book belonging to something greater than itself. I suppose I might overthink epigraphs but as an editor, I see them all the time, and when there’s an epigraph, for example, that’s longer than a poem, I find it frustrating. Any epigraph preceding short fiction or poetry drives me crazy. In novels, I suppose an argument can be made for them. I don’t know. They just bother me. It’s a silly thing and yet it isn’t.

I like epigraphs in books but don’t like them for individual works. A novel has a lot of influences, and often one or two of those might have been the starting point, or could clarify, the novel. I want to avoid the argument that the book should already be clear enough, or the influences should already be or are already visible within, because I think there are many ways to tell a story, and sometimes the epigraphs are a well-used tool and sometimes they are not. Just like everything.

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

tinyurl.com/24n4nqb

All books should be rectangular.

From “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”:

“Persons attempting to find a motive in thisnarrative will be prosecuted; personsattempting to find a moral in it will bebanished; persons attempting to find a plot in itwill be shot.””IN this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods Southwestern dialect; the ordinary “Pike County” dialect; and four modified varieties of this last. The shadings have not been done in a hap- hazard fashion, or by guesswork; but painstakingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech.I make this explanation for the reason that without it many readers would suppose that all these characters were trying to talk alike and not succeeding.”I can understand, Roxane, your annoyance with prefaces, author’s notes, epigraphs, and so on, but I have to say that both of these, in their own way, enrich Huckleberry Finn. Would TAoHF be a ‘lesser’ book without them? It would still be great, but surely nothing is lost. And the disclaimer concerning dialect is a tongue-in-cheek and particularly wise expression of the principles necessary to rendering dialect on the written page– that is to say, that the point is not absolute accuracy, but given experience and familiarity, the semblance of ‘authenticity’.Perhaps you can suspend your annoyance for that minor American novelist, Mark Twain, in his most minor of books?

I am unilateral in my dislike of prefatory material, from writers as great as Twain to writers yet unknown.

tinyurl.com/24n4nqb

. . . . . . the Confession of a White Widowed Male,” . . . their author . . . died in legal captivity . . . a few days before his trial was scheduled to start . .

. . . For the benefit of old-fashioned readers who wish to follow the destinies of the “real” people beyond the “true” story . . . “Mrs. Richard F. Schiller” died in childbed, giving birth to a stillborn girl, on Christmas Day 1952, in Gray Star, a settlement in the remotest Northwest . . .

. . . had our demented diarist gone, in the fatal summer of 1947, to a competent psychopathologist, there would have been no disaster; but then, neither would there have been this book . . .

. . . should make all of us – parents, social workers, educators – apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world.

The part about epigram, epilogue, prologue, was fun to read. Thanks.

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

I am unilateral in my dislike of people who make their unilateral dislike of prefatory material public knowledge. IT DOESN’T MATTER WHAT YOU THINK!

irrational hatred of prologues and epilogues used prologuely and epiloguely as a frame for a review. i’m not sure if i’m supposed to be reading this as a kind of genius and ironic rhetoric since i am personally frustrated at having to read through all the hatred of prologues and epilogues (which dont really bother me in fiction) just to get to the actual review, but in doing so can’t deny that I now share the same frustration with the review that roxane shares with novels.

Presumed air of authority.

I am expressing my opinions so yes, there would (and should) be an air of authority about them since they are mine. I should hope you would have authority over your own opinions.

Junior high school comment

MFA comment

MFA comment

i think what the review is saying is fine, except I wouldn’t mention all the prologue/epilogue because it comes off as petty. but it feels like the writing needs a lot of tightening up. there are moments like these that make me cringe…

That said, as a debut novel, Rules of Civility is a real wonder and I’m excited to read it again, and again. Rules of Civility was

a real surprise and I took great pleasure in seeing a modern novel do

something fresh with a style of writing we often assume has fallen by

the wayside.

It’s the double use of the title that nails it here, like a student trying to edge in a word count minimum.

and this…

The story being told in Rules of Civility is simple and one that has been told before but what really elevates this book is the manner in which the story is told.

One too many “tolds” perhaps? or maybe “manner” should be italicized because im reading it in my head as very monotone and the tolds in the beginning middle and end just stick out as too repetitive.

I mean a lot of what’s being said in the review i think is fine, but it doesn’t feel like any editorial effort went into it at all, like it just needs a lot of tightening.

GET THIS PERSON A REFUND ASAP!

refund for what? the review was useful, i just thought it needed tightening.

John Ray (Gen Re)

Bah: D‘Invilliers. Apologies, Thomas.

Roxane,

When you hold such an inflexible view and one you apply “unilaterally,” isn’t it time to examine it? I guess this review is such an examination. But isn’t every thing situational? What might be dumb or pretentious in one piece might be brilliant in another. I love the epigraph. And, of course, some works don’t need them, but they can do a good job of “teaching” the reader how to approach a work. It can also be an acknowledgement that your ideas, themes, characters, etc. are “connected” to ideas from other works.

I would estimate that about 80 percent of the epigraphs I have used in my fiction are made up out of whole cloth. The works and their authors don’t really exist. Then that can add another layer.

As for the prologue….I wouldn’t want to live in a world in which the prologue of Invisible Man was never written. Straight brilliance. One of the best things I have ever read and the book would suffer without it. If the prologue was all the existed of that book then that would be enough. Then the epilogue….beautiful. The best prologues and epilogues are integral to the structures of the books and should be judged on their own merits. It’s not fair to reflexively reject them.

This post needs an epigraph.

epitaph

This post needs a eulogy.

Rion, certainly all beliefs should be examined from time to time. There are exceptions to everything. Within the context of this review, I felt as if the preface and epigraph were not necessary and I feel like I clearly explained why. My overall view on epigraphs/prologues/epilogues is not actually as inflexible as it seems. As I noted in an earlier comment, someone made a good point about epigraphs serving as a marker that the text it precedes is part of a larger body of work. I am well aware that there are books where prologues work quite well though I believe this to be a rarity. Invisible Man is, indeed, one of these exceptions, where the prologue and epilogue are examples of beautiful craftsmanship. For every Invisible Man, though, there are hundreds of novels that do not use prologues and epilogues in ways that are integral to the structures of the books. This is merely my opinion.

tinyurl.com/24n4nqb

tinyurl.com/24n4nqb

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

University of Phoenix exchange of comments

night school (with discount coupons)

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

ta.gg/532

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

alturl.com/dvxpf

I constantly fail to get why any particular epigraph was attached to any particular work, but I pretty much always like that they’re there. The idea of picking epigraphs to put at the beginning of things makes me want to write more things.

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

[…] Roxane Gay looks at Amor Towles’s Rules of Civility: “The writing reflects the writer’s meticulous understanding of the tradition of writing preceding him, particularly the work of Fitzgerald and my beloved Edith Wharton.” […]

alturl.com/dvxpf

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

[…] at HTMLGIANT, I reviewed one of the best books I’ve read this year, Rules of Civility by Amor Towles. I’m quite […]

alturl.com/dvxpf

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

tinyurl.com/2df4ccp

alturl.com/dvxpf

On epigraphs, etc., I tend to agree..

I understand that it’s exciting to buttress one’s views with others, and to provide links to things to embellish one’s own tastes, and that we are all part of a contextual conversation by virtue of being alive, but I think it can be braver, more exciting, and ultimately truer to just say something without mediation.

why are you reading her review I wonder?

I just finished reading this and I think your review is spot on, especially about the chapters from Tinker’s POV – they didn’t seem to gel with the narrative or reveal enough for my liking. But what a delicious, memorable novel.

Thanks for the handy epigraph. :-)