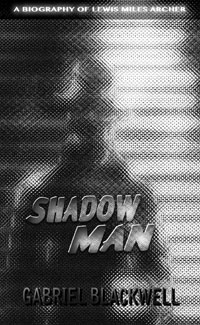

Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer

Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer

Edited by Gabriel Blackwell

Civil Coping Mechanisms, October 2012

286 pages / $13.95 Buy from Civil Coping Mechanisms or Amazon

Is there a form called smart noir? There should be. In Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer, published by Civil Coping Mechanisms, Gabriel Blackwell both conducts and writes the story. As the meta-writer and the meta-detective, he’s inside what happens, and outside, all at the same time. Blackwell claims, rather coyly, to be the “editor” of Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer, and he is listed as such on the cover. But like a savvy gumshoe, Blackwell is too humble—and too sneaky—to list his skills upfront. His project is to blur lines between fiction and nonfiction; genre and form; noir and innovation.

We should consider ourselves forewarned meta-readers because Blackwell, as editor of this book, as author and researcher, is the ultimate shadow man. Blackwell disappears into the story and lets us know that he will be seen—and not seen:

We read to name that “pink elephant” in the room and, in the manner of noir, to find that missing femme fatale in the bar. The reader’s suspicious impulse might be to sit with the book and with Google, to search what is fiction, nonfiction, or imagination. We are inside the story as it unravels and outside the story as it is revealed. The story becomes confounding, like “a maze”:

I soon gave up the inter-textual Google approach to reading Blackwell and let myself be drawn into the cheeky editor’s devilish and impish fun. Those who are unseen and unknown are often the characters of literature that might reveal the most, were we to bother to ask. Blackwell bothers. He uses this knowledge, his questions, to great effect, illuminating a man who existed and didn’t exist, someone who disappeared with nary a backward glance.

Shadow Man takes as its cue Dashiell Hammett’s fictional detective Miles Archer, and jazz riffs off of Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald, too. Nevertheless, before you think you must be familiar with works by those three, consider that I’m not all that familiar with noir, and I found myself thoroughly, willfully engaged. Submerged.

The reader’s project might be similar to investigators who uncover eyewitnesses. The reader uncovers characters and characterizations. The book shadows (that word again!) the character Archer through different appearances. If we are all dicks (detectives, I mean), then our tracking is perpetual: Our reading goes on, detective-like, tracking femme fatales, missing falcons, and Archer.

Dashiell Hammett used a fictional detective, “Miles Archer,” but Blackwell illuminates the fictional with the real dick behind the story, Lewis Miles Archer, who was Hammett’s partner and a real detective. I’m a fan of union history, so the references to Pinkertons thrilled me (and seemed prescient to our times with the recent union-busting laws in Wisconsin and Michigan). Archer writes in his detective’s notebook, which is included in Shadow Man, and thus gives us more reading clues: “It’s all up front. Everything’s a front.”

Blackwell’s exhaustive noir knowledge of “no-name Joes, guys with names that mean bunk” means that we are in the hands of a gleeful guy. Blackwell is our leading private eye:

Which leaves Archer out in the cold, on Union Square in mid-December with no hearth to go home to. Hammett’s account of the events after Archer’s murder in The Maltese Falcon doesn’t exactly paint Hammett in the stained glass as the White Knight, so there’s probably some truth to it. In the novel, Hammett gets wrapped around Iva Archer’s little finger, turns the bird over to the police, and lets Wonderley flap in the breeze.

The girl stays out of the picture—that’s for sure. Daddy’s money takes care of that.

Again, one feels the impulse to fit the pieces together to follow this detective author, but even that impulse—to make sense of literature or to make literature make sense—is rightly questioned in Blackwell’s astute hands. To create Lewis Miles Archer, Blackwell borrows from Hammett. The momentum behind The Maltese Falcon forms the genesis of Shadow Man. Then Blackwell creates. He conflates. Blackwell borrows from Raymond Chandler, from Ross Macdonald.

Blackwell challenges our desire to build character through illumination, filling in the animus not by erasing the past but by including the past and adding to it. Recall one of the Latin quotes at the start of Shadow Man that tells us that “although changed, [he] shall arise again.” The story here, although changed, rises again. Built on narrative history, it’s also built on its own beginnings:

While creation arises from imagination, the source of imagination might be uncannily familiar. We are literary cannibals, all. The mystery forms the wicked fun of this meta-critical project—but Shadow Man stands on its own, aside from its meta-critical inquiry. After all, as Blackwell writes:

It’s noir, it’s your shadow, it’s Borges’s interweaving maze-like blindness. Let narrative loose under klieg lights and watch narrative lose its mystery. Keep narrative shrouded in a dusky haze, and let narrative reclaim its mystery—of form, of story, of meaning.

***

Renée E. D’Aoust’s first book Body of a Dancer (Etruscan Press) was a Finalist for Foreword Reviews 2011 “Book of the Year.” She teaches online, lives in Switzerland and Idaho, and helps her dog Tootsie write a blog [http://bicontinental-dachshund.blogspot.com]. For more information, please visit www.reneedaoust.com.

Tags: civil coping mechanisms, Gabriel Blackwell, Renée E. D’Aoust, Shadow Man

I’ve been wanting to read this but have also wanted to read its most direct references first. Thanks for reminding me to do those things.

Hmm. I’m not a noir fan, unless there’s an element of fantasy or super hero involved, but this sounds interesting. Thank you.

I’ll have to tell my Mum about this book, she’s always looking for new things to read!! :)

I hope you’re having a fun day,

Your pal Snoopy :)

I need to explore noir literature as I’m just beginning to enjoy the film genre. Thanks for the cool, provocative review to motivate me!