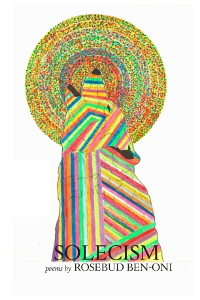

Solecism

Solecism

by Rosebud Ben-Oni

Virtual Artists Collective, 2013

80 pages / $15 Buy from Powell’s or Amazon

The phrase “identity poetics” has always struck me as strange. “Identity” comes from a Latin word that means most nearly “being the same,” and “poetics” from an Indo-Euro base for “one who collects, or assembles.” But “to be the same as one who assembles,” means every poet’s an identity poet, and from certain angles, dripping wax over thester scrolls in a dank hovel of some dentine tower, that’s probably true. But I’d wager most people interested enough in “identity” to consider it together with “poetics” consider the “id” (most literally just simply “it,” as in “id est”) in “identity,” and thus some other entity must assume that pesky pronoun. Hence, identity poetics qua the familiar orientations: sex, class, and the hyphenate ethnic camps (African-, Asian-, Latin-, et c.).

But when a poet’s got not just one, but two (or more), and wildly—let’s not say oppositional, but incommensurable—competing and/or complementary identities, the poetic stakes increase exponentially. So’s the case with Rosebud Ben-Oni (whose given name trumps any nom-de-plumes that arise to mind). Daughter of a Jewish father and a Mexican mother, Ben-Oni’s poems carry that heritage into the nonstandard impropriety of Solecism, a book of exodus and translation. These poems, rooted in autobiography, enact politics in ways that fail to strike one reluctant pedant as even remotely didactic.

Ben-Oni starts with the motherland and charts expanding circles with Israel, Mexico, and Manhattan at the respective center of each. The book’s scope expands to encompass the Middle East at large, all the borderlands’ length, and the greater metropolitan boroughs, winding up finally in Hong Kong (we’ll get there). Her course proves most interesting when these circles intersect, as with forgotten, historic Baghdad Beach of Matamoros, Mexico (which even seagulls, it seems, seek to flee) or Mt. Scopus, “an Israeli enclave in Arab East Jerusalem,” a territory likewise divided.

Ben-Oni’s poems don’t seek to bridge these divides or to reconcile a sympathetic speaker to this world defined by walls. Neither does she let the reader waffle in some non-space of dialectical nonsense. Instead, she collects words and phrases from across several languages and dialects to shape the collection’s texture, composed as much of Prospect Park and Flushing, Queens as it is tahini and achiote. Ben-Oni italicizes select words in Spanish (“colonia”), Hebrew (“dabar”), and Arabic (“wadi”), which she defines in footnotes, plus others in English, now chiefly North American (like “rawboned,” e.g.). The effect at first is like that old adage about Dick Branson tossing darts at a map: it may seem scattershot and haphazard, but the lexical globetrotting echoes always those sites I have to believe Ben-Oni’s speakers call home, strong as the drive for relocation may be.

The book opens with a series that invokes “Sal Si Puedes,” an imperative she translates as “Leave if you can,” with reference to barrios in the U.S. and Mexico. The last of these, “The Reply of Sal Si Puedes,” includes the most disseminated sample from Solecism:

Parvenu to be archaic.

Autistic to partake in restoration.

Novel but not like neon-plated

Tijuana, a peso who thinks herself a penny.Can’t be museumed.

History skips over my life.Confused that I speak intelligently?

Think the pinched aren’t polysyllabic?

Wordplay gives way to rhythm, as Tijuana emerges lit-up like Las Vegas. The speaker confronts detractors with blunt direct inquiry, plus of course the extra unstressed syllable in that great final line. Elsewhere, words unfamiliar to at least one whitebread Midwesterner introduce thematic threads. “Sabra” pops up, which denotes a thorny pear grown on cacti in Israel, but can also refer to native Israelis, the connotation born of the fight against discrimination suffered after mass immigration in the 1930s and ‘40s. Several pages later I had to look up “oud,” happy to find a picture of the pear-shaped instrument on Wikipedia. In other images, Ben-Oni contains language in equally emblematic objects. “Crossing in Brazier Fumes” offers an odd transliteration:

The sound of me

in Hebrew means “who”

& who is “he” & he is “she”

A second person shows up as the lines diverge from the left margin, jumping across the page into a kind of conversation:

the voice of a sheik buzzing behind you.

A casual scratch behind the hand;

Let’s go before the sun comes up.

You dress quickly, will fast like a martyr

for another day and ace the oral with a blank face

while silently cursing us in your own language.

Who is He is She?

This lingering question brings gender identity to ethnic and religious legacy in a way that dilates Solecism’s focus, but keeps incongruity and irregularity at its center. Likewise, “The Current Political Situation of the Roma,” arranged like a dialogue between an ideologue and critic (or artist and editor), explores corollaries between folks known colloquially—albeit non-PCly—as gypsies, and Jews and also migrant Mexicans. This is Ben-Oni at her best: where the “it” of identity arises and the cross-section of Mexican/American/Jew’s made explicit.

And here where we arrive, finally, at Hong Kong.

If Ben-Oni’s debut wants for anything, it’s fixity. The book’s all departures and contrails, seeming never to settle or rest. Between Chinatown, the Wailing Wall, and Texas border towns like Brownsville, it’s never more than a beat before we’ve jump-cut across the globe. This is part of the pleasure, of course, and the challenge, of reading Solecism, and we learn in an appendicular aside that the poet finished revising the book on a rooftop deck in Hong Kong, far removed from the cultures that occupy most of the poems. This detail surfaces, briefly, in verse, and I’m led to wonder whether this collection, so filled with the proper names of places, houses voices that must be, ultimately, placeless. Which I think makes sense for Ben-Oni, as she writes a territory that describes the Venn-like layering of wandering Jews, migrant Americans, and 7 Train straphangers. Yours Truly looks forward to her future work, to see it continue to navigate the twisting flux of her coexistent identities, to see which directions it takes her.

***

Diego Báez writes regularly for Booklist and Whole Beast Rag. Other work has appeared most recently in Kweli, Treehouse, and Hobart. He lives and teaches in Chicago.

Tags: Diego Báez, Rosebud Ben-Oni, Solecism

tinyurl.com/l3cselt