Sniffingly we are nearing the end of STARK WEEK, as we round the corner into the last book, Self Help Poems, with the fantastic Amy Lawless onboard to epically investigate. Don’t put your boots away yet because there is more to come, including prophecy, art talk, videos, and contests!

I have asked myself many times why actor Mickey Rourke is so appealing and attractive to me. Over time he has aged, yet he still manages to allow us, the consumers, access to another human place and plane. Sampson Starkweather doesn’t use the words “appealing” or “attractive,” but he writes on how Rourke’s “therapist told him he was in a hopeless situation, but he still had hope. All humans aspire to the condition of Mickey Rourke” (255). Here on the ninth page of Self Help Poems in The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather, hope emerges, which makes sense because man is a social animal—we are each other’s only chance of salvation.

I have asked myself many times why actor Mickey Rourke is so appealing and attractive to me. Over time he has aged, yet he still manages to allow us, the consumers, access to another human place and plane. Sampson Starkweather doesn’t use the words “appealing” or “attractive,” but he writes on how Rourke’s “therapist told him he was in a hopeless situation, but he still had hope. All humans aspire to the condition of Mickey Rourke” (255). Here on the ninth page of Self Help Poems in The First Four Books of Sampson Starkweather, hope emerges, which makes sense because man is a social animal—we are each other’s only chance of salvation.

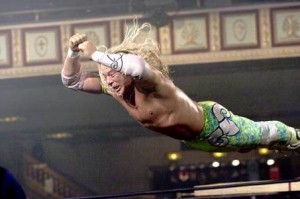

Mickey Rourke is not tricky; he is wise—body-wise. In the film The Wrestler, viewers followed him into an oblivion, a place we all go (some of us more quickly than others). Some of us are tiptoeing as slowly as possible toward death with our many fish oil supplements, mountain poses, punitive juice cleanses, hand sanitizers, Deepak Chopra books, or prayers. Some of us are in a speeding car wearing no sunscreen, driving as far away from prostate checks as possible, pumping the speedometer far right with a recklessness our mothers should never know exists. We are each Mickey Rourke jumping off the rope toward our own single finality.

These poems are driven by the idea of hope, but does hope help the self? Starkweather might agree with the idea that a poem has no obligation, can do anything. However, he writes “[t]he reason poetry works, ‘real’ poetry, is that it has no pretensions of being real, it doesn’t care if you believe, it doesn’t even believe in itself, it is, or rather, it is just…language, which, only on its own is perfect, believable….” (278). And yet, this is a poem with a clear, persuasive intention: by holding on to language, something greater, anything/something/magic can happen.

Once a boyfriend dumped me and one of my immediate reactions was to read a self-help book. The book did its job: it helped me by reading and focusing—to get over him. The book asked me to do things like kill my ego, consider he who hurt me as just an animal being with limited power and reach and problems of his own so that I should feel lucky to have unhooked from, that I have my own wingspan, and to just move on with my badass self. But that’s not what a Self Help Poems poem does.

The speaker may get as much out of these “epistolary” prose poems as the recipient whom he is writing to and “helping” (that is all an unquantifiable amount of help).

Starkweather writes:

Maybe if I threw up pints of blood and passed out on my porch in my work clothes waiting for someone to find me the way my dad did when he was a little older than I am now, and maybe if that person who found me was you, then I wouldn’t need to write to you anymore. (300)

That is a cry for help—needing help. Is writing this poem helping the self? Is reading the poem putting things into perspective? Does perspective imply the recipient doesn’t have things so bad? There’s no real answer because all answers are valid and possible and ambiguity is a good place to idle the mind. Please help me or help yourself.

The speaker’s own journey is one of hope, introspection, personal history, and legacy. The work utilizes poetry as self help, as definer of fear of something and fear itself, as diviner of chaos that includes responsibility, suicide, AIDS, the desert, impermanence, the death of an uncle, beauty, Mike Tyson, weird shit that you can’t explain but need to tell of again and again in different ways. I felt similarly after reading the work of Gary Lutz and Raymond Carver. That is to say, the chaos of the world we live in is underscored, not solved.

The speaker’s own journey is one of hope, introspection, personal history, and legacy. The work utilizes poetry as self help, as definer of fear of something and fear itself, as diviner of chaos that includes responsibility, suicide, AIDS, the desert, impermanence, the death of an uncle, beauty, Mike Tyson, weird shit that you can’t explain but need to tell of again and again in different ways. I felt similarly after reading the work of Gary Lutz and Raymond Carver. That is to say, the chaos of the world we live in is underscored, not solved.

The poem is also concerned with the disappearance and/or death of the speaker’s uncle Tony, who first appears in his absence:

Did I tell you how I Google my uncle at least once a week? Sometimes I add search words to his name like some kind of fucked up equation, Tony Newhall + drown + Phoenix + one wing. All I ever get is different douchebags’ LinkedIn profiles. It’s not like I expect to see a home video of him standing in front of a waterfall telling me how one leg is full of food and the other is hollow. I’m not naïve. One day he’ll come through, I just know it. (272)

Here the speaker is hopeful that he who is gone will return; the poem nearly ends on the daring claim of negating/rejecting naivety, and yet the content of the final sentence indicates a certain naivety. And yet, for the poet, the dead uncle is associated with resurrection:

Tony burst through the door like a kind of electricity and said, holy shit, one of the ducks had resurrected. One by one, the ducks, with trouble, as if coming out of a long sleep, slowly rose up, and in the bliss of remembering nothing, wobbled off into the yard. (290)

Starkweather wants his uncle to Lazarus back into his life. The uncle, described as “a kind of electricity,” went missing in a mysterious way, and left the door open for his own return. And now he’s gone. Ducks made it back, why can’t a human?

Well, why can’t he?

It is helpful to frame “The Case of the Missing Uncle” through a paradigm that one understands, and Starkweather could have chosen anything: his interests are broad. Starkweather’s narrator in part frames it through the language/setting/lens that began the poem: wrestlers on TV. Starkweather embroiders wrestlers with (whether on television or being interviewed on Charlie Rose or in person) his own (or a speaker’s own) mourning pain and frustration. Uncle Tony is not a wrestler. The speaker of the poem is. And he is using wrestlers to wrestle with feelings and pain and mourning and frustration. He wrestles. Here:

This is not a poem about ducks. This is about the night my uncle died. Randy Savage was fighting Honky Tonk Man—the Hart Foundation ganged up on Macho Man as Honky Tonk pushed Miss Elizabeth then smashed his guitar over Macho Man’s head while the Hart Foundation pinned down his arms. The night of no-longer-waiting. Sold-out Hershey Park Arena. The Saturday night Main Event. The crowd going wild. Deafeningly alone.

Who is alone? Not Miss Elizabeth, not Macho Man, not Honky Tonk Man—they’re all having a fine time. The narrator is alone. Alone because Uncle Tony was gone—or simply that the adults were freaking out, making phone calls, alone because everyone was crying, alone because: how can one express the attendant pain of losing an uncle who can raise the dead, a father figure? How does one put that feeling into words? And once those feelings are IN WORDS, does that make one ever, ever feel much better? There’s no answer. But deafeningly alone is a good way to begin to describe it. Alone without one of the given five senses in the loudest place imaginable.

Mike Tyson isn’t a wrestler; he’s a boxer, and I know, I know—those are two different sports. Both sports use human bodies to inflict violence in a ring situation. Starkweather writes how, one night on the Charlie Rose television show, Mike Tyson “…just blurted ‘malice’ out of nowhere, as if it was something he had been thinking of for years and just remembered. Everyone at the table looked as if they thought their life was at stake. Mike leaned back and smiled. There is such a thing as genius of experience, the genius of victimhood, the genius of shame. Then again, a man ain’t nothing but a man” (265). Though chiefly body-wise, Tyson here uses language to threaten those around him.

Mike Tyson isn’t a wrestler; he’s a boxer, and I know, I know—those are two different sports. Both sports use human bodies to inflict violence in a ring situation. Starkweather writes how, one night on the Charlie Rose television show, Mike Tyson “…just blurted ‘malice’ out of nowhere, as if it was something he had been thinking of for years and just remembered. Everyone at the table looked as if they thought their life was at stake. Mike leaned back and smiled. There is such a thing as genius of experience, the genius of victimhood, the genius of shame. Then again, a man ain’t nothing but a man” (265). Though chiefly body-wise, Tyson here uses language to threaten those around him.

Later, after getting staples gunned to his head after a sports injury, Starkweather writes: “I felt like Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler. But not in the Hamletesque depth-of-the-soul sort of way, just in the middle-aged-dude-shot-full-of-metal-staples sort of way” (267). Through these two frames, the speaker is able to connect himself, his outward physical manifestation and masculinity to a moment, a traumatic event. Blurting a word violently, a word that means to threaten evil, a need to see others suffer allows a true human to manifest into something greater—an altering of reality with a single word. The near apotheosis of Tyson? Wrestlers and boxers are people whose bodies are destruction personified. If Tyson, the body-wise, can make something happen with a single word, changing one’s environment, then bringing a man back to life might just be one Google search away…

Wrestling and boxing are violent sports. They are primarily engaged in by men (though not exclusively). While or shortly after the speaker heard of an uncle’s death, he connected to a television screen and surely not intentionally, sucked the images down into the thirsty heart/mind. Oh! I just want to cry because I am picturing the eleven year-old Sampson Starkweather, at an impressionable age, with his biblical character and serial killer’s name, needing a connection, an anything-else to prop his humanity against.

Wrestling was on TV that night while the void’s door was ajar.

Another example of wrestling occurs when the narrator’s grandmother watched her adopted grandson, Louis, wrestle while wearing a Mexican Wrestling Mask in west Phoenix. She said “’mi,’ tears welling in her eyes, at this, the happiest moment of her life” (292). Was it her happiest because two days after her husband died she was watching a boy, a grandson, take to the ring and engage in a struggle all-too-human, violent, for life, dramatic? Was this struggle made more complicated by her recent grief? Was it enough, just this once, to see a young man on the stage, fighting with his body, with the poetry of his human form, slouching and fighting messily against the that which we don’t know is next? Were the grandmother still alive, I’d point her to Self Help Poems, a book made only of her grandson’s words. The book is fighting back at what’s coming at it pretty hard, and in it we all have a chance to cheer on, for our struggle is no different: we hope and we hope for things. It’s beautiful like Mickey Rourke because the struggle exists. We hope and we hope for, and we fight on. Each breath is a swing in the ring. A word is a swing saying yes to living.

Another example of wrestling occurs when the narrator’s grandmother watched her adopted grandson, Louis, wrestle while wearing a Mexican Wrestling Mask in west Phoenix. She said “’mi,’ tears welling in her eyes, at this, the happiest moment of her life” (292). Was it her happiest because two days after her husband died she was watching a boy, a grandson, take to the ring and engage in a struggle all-too-human, violent, for life, dramatic? Was this struggle made more complicated by her recent grief? Was it enough, just this once, to see a young man on the stage, fighting with his body, with the poetry of his human form, slouching and fighting messily against the that which we don’t know is next? Were the grandmother still alive, I’d point her to Self Help Poems, a book made only of her grandson’s words. The book is fighting back at what’s coming at it pretty hard, and in it we all have a chance to cheer on, for our struggle is no different: we hope and we hope for things. It’s beautiful like Mickey Rourke because the struggle exists. We hope and we hope for, and we fight on. Each breath is a swing in the ring. A word is a swing saying yes to living.

Amy Lawless is the author of My Dead (Octopus Books, 2013). She lives in Manhattan.

Tags: Amy Lawless, charlie rose, El Carcelero!, genius of experience, mickey rourke, mike tyson, stark week, the genius of shame, the genius of victimhood, uncles

FUCK YEAH AMY!!

Best Starkweek post yet? Probably.