I.

I’ll let you fuck me

if you make it quick.

Like mechanized.

Like we both come

and that’s it.

No funny business

in between.

Those four sentences uttered by the narrator of Juliet Escoria’s new book, Witch Hunt, published recently by the critically acclaimed indie press Lazy Fascist, demonstrate the precise composition, emotional wreckage, and elegance of language on display in this powerful text.

The passive first line compared to the assertive lines directly following illustrate the text’s general ethos: deadpan checked-out ghosts of people bumping into one another’s atmosphere where desire forms and floats without anchor. Still, these ghost people transform drug addiction, mental illness, suicide, domestic abuse, political correctness, formal experimentation, epistolary, haiku, conceptual, confessional, visual expectations.

So many ghost people exist inside her sentences. So many performances. From the opening section of the ten-part long poem titled “True Romance,” where the above quote originates, the speaking subject comes into focus so quickly and so resonantly, readers sometimes mistakenly presume to understand Escoria’s speaker way too prematurely. It’s true we come to know a person in the pages of Witch Hunt, but through the course of the book the speaker remains unflinchingly unpredictable. What she does one moment doesn’t forecast what she’ll do in another. To assume to know the narrator, to expect to know what she will say or do or think at any moment proves preposterous. Since this passage appears late in the book, readers who start at the beginning and move forward in the standard reading fashion (as opposed to skipping around) already know they don’t know what’s coming next; what distinguishes this particular moment in the book is the role it plays in the overall structure of Escoria’s fragmented twenty-first century confessional romance narrative. It begins the descent to terminus.

Hopefully the following notes convincingly attest to the raw elegance of Witch Hunt, while nevertheless ultimately revealing my strong admiration for it. As we enter the darkness of 2017 — don’t forget, those Game of Thrones people kept warning us the winter was coming! — let us not forgot this powerful 2016 release. Escoria taps into something vital about our current cultural condition and engages with it in provocative ways. So here’re my thoughts on why I highly recommend it:

Ia.

But first, my preferred accompanying music to Witch Hunt: Montréal-based upside-down deconstructed sludge doom swing punk ambient drone chant riot metal trio Big Brave’s newest (perhaps third?) album, Au De La, which I’d describe as slowed down, punch-you-in-the-gut and stomp-on-your-foot-in-the-dark type of rock and roll, a grimy sound complicated by the viperlike punctuation of the female vocals which loop and linger and scratch and puncture all around from breathy huffs to snapping growling howling to cooing to conjuring metaphysical entities. A miraculous pairing with Witch Hunt. They totally hold hands.

II.

Ugliness shapes an important and valuable aspect of Witch Hunt. Abjection on view. For me, it brings to my mind the realist work Émile Zola conducted at the end of the 19th century. In particular I’m thinking about Zola’s important (if all but forgotten) essay The Experimental Novel where he discusses the work of French physiologist Claude Bernard. Zola quotes Bernard as saying, “The experimentalist is the examining magistrate of nature.”

If we buy that line, I’d say Escoria (as the experimentalist here) does a superlative job at the description of that title. Across the text we find evidence of her keen ability to examine the nature of her existence, especially in relation to others. In one section of “True Romance,” for example, she divulges a moment when she bathes in her lover’s feces, which registers as simultaneously sad, gross, and yet weirdly touching. In another section of the book, the narrator discusses her pimples and boogers and fingernail clippings. In another section the narrator offers the reader a drawing of a creampie: semen dripping out of her vagina. Granted, these indecorous subjects could easily succumb to melodrama by indulging solely in their shock value. Escoria, however, avoids this pitfall by establishing such a strong and compelling presence, by owning her position as a human animal full of ugliness and prettiness combined. Few writers possess the confidence and willingness to expose themselves in all their beauty and abjection so evocatively. To lay oneself bare before a live audience, as Escoria does in this book, requires a tremendous amount of vulnerability. And courage.

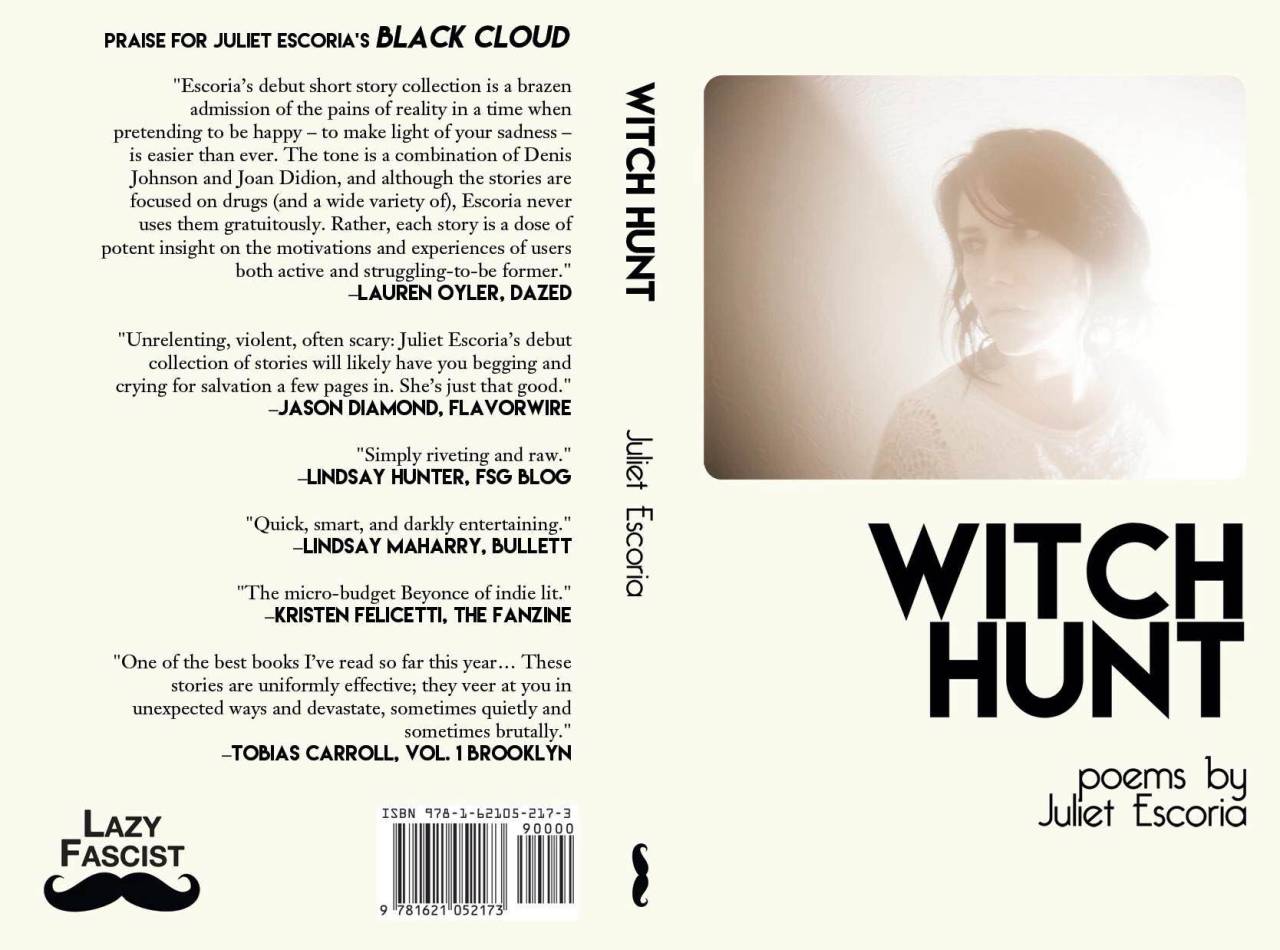

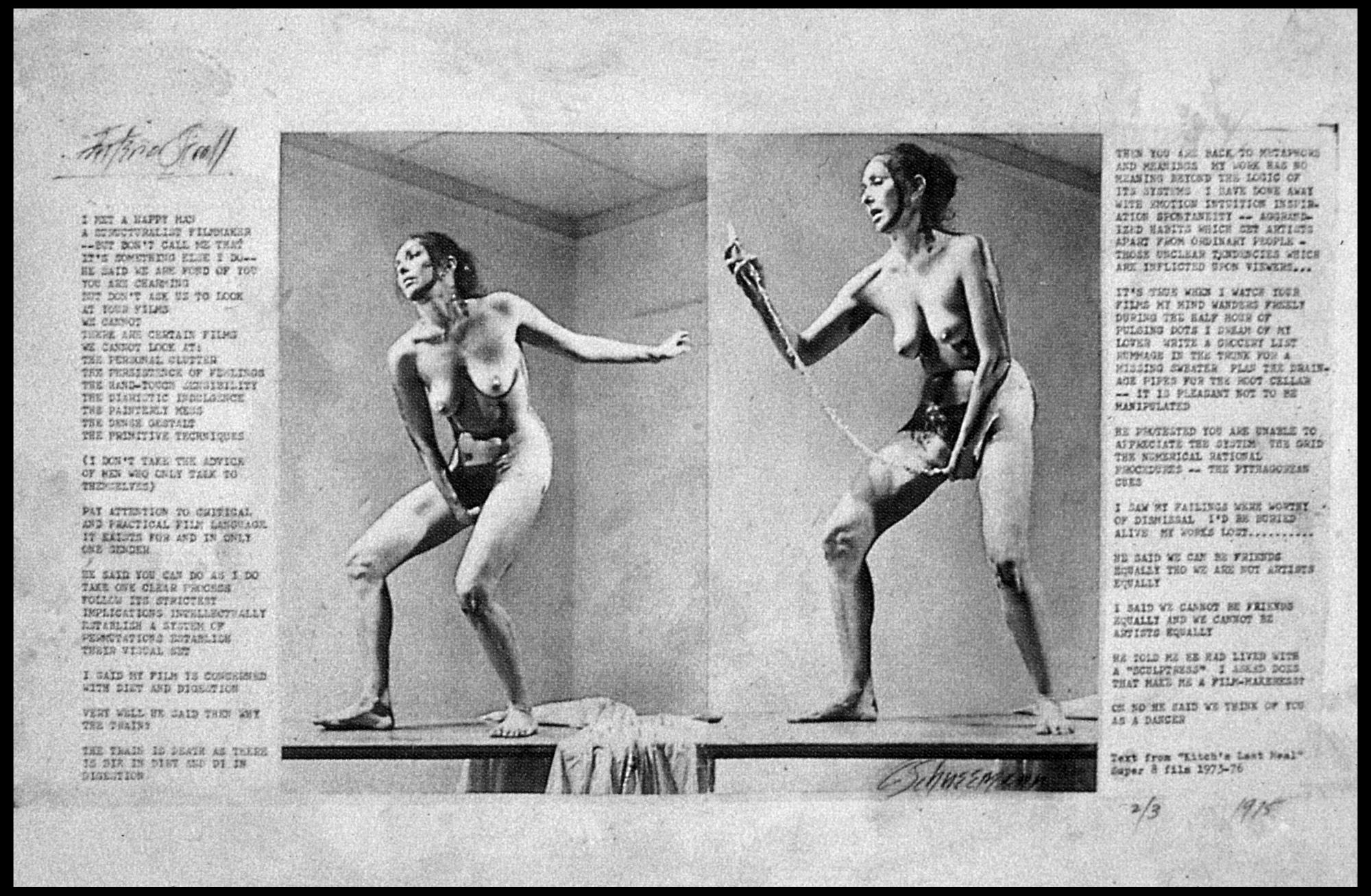

IIa.

Carolee Schneemann, “’Interior Scroll” (1975)

III.

From start to finish, Escoria’s presence on the page as a stylist remains for me the most exemplary feature of Witch Hunt. Both formally (in its architecture and construction) and in terms of content. Her sentences perform her strengths in convincing displays of details, of traits and backstory, of moments caught in a glimpse, so as to persuade even the most skeptical of readers to indulge in this particular look at heterosexual romance in the twenty-first century: not exactly the typical example of traditional values, but then again not wholly unalike. A flirtation with both convention and transgression. Always each sentence enriched by an attitude, a style, a swag, an element of Robbe-Grillet meets Kathy Acker meets Courtney Love meets Debbie Harry meets Barbara Kruger meets Betty Tompkins meets Aurel Schmidt meets Charles Bukowski meets Sylvia Plath meets Aubrey Plaza, with heavy echoes of early Hal Hartley.

IIIa.

William Blake’s The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy, often referred to as The Triple Hecate or simply Hecate (1795)

IV.

At the beginning of Witch Hunt we witness the birth of a romantic relationship before moving through its slog, its horrors, as well as its moments of resounding affection and reasons for redemption. In the end, it closes on a sentimental note unafraid to shy away from its sincerity. On the contrary, Escoria’s narrator pushes sincerity to a tipping point, as if she’s daring the reader to flinch. To be honest, some moments in this book hurt to look at. It brings to mind that thing filmmaker Michael Haneke once said: “The ideal scene should force the spectator to look away.” At various points Witch Hunt forced me to look away because of its intensely embarrassing honesty.

IVa.

V.

“Witch Hunts,” as Kent Russell points out in “They Burn Witches Here,” his amazing piece about contemporary witchcraft in Papua New Guinea, “are like earthquakes and mountain ranges. They pop up in times of seismic change.” We are amidst a moment of seismic change now. With her version of a Witch Hunt, Escoria touches a nerve close to the nucleus of one source of massive cultural intensity; it seems to throb or pulsate on that particular frequency, between the postmodern past, the twenty-first century present, and an imaginary future.

VI.

woodcut from the Malleus Maleficarum (1487)

On May 9th, 1487—three months and five years before Columbus set sail from Palos to “discover” America—two priests, Jacob Sprenger and Heinrich Kramer, submitted a manuscript they penned in Latin titled Malleus Maleficarum to the University of Cologne. While historians disagree about the roles these men played in the creation of the document, it nevertheless quickly became the cornerstone for all witch-hunting manuals across Western Europe. According to the Introduction of Montague Summers’s 1928 translation:

The Malleus was used as a judicial case-book for the detection and persecution of witches, specifying rules of evidence and the canonical procedures by which suspected witches were tortured and put to death. Thousands of people (primarily women) were judicially murdered as a result of the procedures described in this book, for no reason than a strange birthmark, living alone, mental illness, cultivation of medicinal herbs, or simply because they were falsely accused (often for financial gain by the accuser).

Summers goes on to say, “The Malleus serves as a horrible warning about what happens when intolerance takes over a society.” A relevant warning today from nearly 100 years ago.

With the unquestionable and infallible position of the all-powerful pulpit, what a tremendous amount of damage the Malleus Maleficarum (or in German “Hexenhammer” or in English “Hammering the Witch”) caused. Overnight, Men gained the legal means to formally subjugate women. To be fair, the Church ultimately banned the Malleus Maleficarum formally three years later in 1490. But even then, the list of accused or admitted witches continued to grow, according to Margaret Alice Murray’s monumental 1921 text The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. Not to mention the present day examples of women being tortured and executed for accusations of witchcraft and the practice of black magic, as The Washington Post has reported.

VIa.

“Witches’ Sabbath” (Goya, 1798)

VII.

Considering and then ultimately rejecting the term “Witch Theorists,” distinguished historian Brian A. Pavlac coined the term “Strixology” to define the critical study of witchcraft, “a genre moving beyond general demonology to focus explicitly on witches,” in his recent scholarly text, Witch Hunts in the Western World: Persecution and Punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem Trials. One of the key tasks of the Strixologist, according to Pavlac, involves determining the validity and truthfulness of witchcraft. Are magical powers real? Can women harness metaphysical powers? Are women possessed by evil or do they invite evil? Does god want us to punish them?

If all history is the history of patriarchy, to play off of Marx, then Independent Scholar Steve A. Wiggins makes an interesting point in his review of Pavlic’s book. He quotes Pavlac as writing, “A history of the Middle Ages shows the intensifying entanglement of magical thinking with political power, which produced the European witch hunts.” And then Wiggins writes, “Substitute ‘Modern Day’ for ‘Middle Ages’ and ‘Planned Parenthood’ for ‘European’ and see if you can’t find a pattern.”

VIIa.

“Examination of a Witch” by Thompkins H. Matteson, 1853.

detail of Matteson’s “Examination of a Witch”

VIII.

Witch Hunt invites confusing mixtures of embarrassing, empowering, and vulnerable emotions, all while playing with persona, playing poetically with fiction and nonfiction while calling itself poetry, playing with form, playing with patience, spotlighting moments of beautiful and ugly simplicity, foregrounding sex of various types and relationships and violence and tragedy and romance and feminism and fandom and idolatry and the everyday, like a glitchy mix, a genuine assemblage in the sense that each seemingly disparate section actually adds another dimension to the body of the collection, deterritorializing reader expectations as well as narrative convention. And again I find myself drawn toward Escoria’s narratives, wondering why these get classified as poems. What does that genre category do? What does it allow? How does it shape reader expectation?

Each section opens different doors, chases different pleasures, and allows the reader a different angle on the narrative tapestry. Each proceeding part makes the picture of Witch Hunt larger than before, sometimes speeding up the reading process, other times slowing it down, sometimes chopping a single word into multiple lines while other times filling the entire page with words in a thick prose block. The only consistency appears to be its inconsistency. Constantly defamiliarizing.

VIIIa.

Cody’s Coop, “Burn Witch Burn”

IX.

I’m watching Robert Eggers’s The Witch. It opens with an overture of cello music playing overtop the black screen. Escoria’s Witch Hunt begins with the deadpan, pathos-driven, female narrator simultaneously kissing a man and wishing to disappear. Shortly thereafter, Witch Hunt changes direction. A few poems center on Guns N’ Roses front man Axl Rose. On page 36 we get a piece titled “Flame War” where she writes:

Everyone is talking about witch hunts

like they’re a bad thing

but I think

it could be fun.

If they had some

maybe I could finally know

how other people looked at me.

Similar provocative claims recur throughout Witch Hunt. One piece, for instance, on page 25, comes off to the present day reader as both clairvoyant and disappointingly indicative of the ubiquity of women’s shared experience of trauma—asks a question about the ramifications of a rape while unconscious from drinking a drugged cocktail—keep in mind this book came out prior to the horrific story of the Stanford rapist Brock (only served three months) Turner—“And if you did something bad, and I never knew about it — does the bad thing have no weight? Does it not matter?” Such an achingly sincere gesture amidst a collection of sincere gestures.

Another piece, on page 39, “Sexy Terrorist Part II,” describes a costume party where the narrator dresses up as the title suggests including handwritten messages on her arms such as “HELL YEAH AL QAEDA / and / DOWN WITH THE USA.” Irreverence bred from the sour conditions outlined by the narrator from start to finish. Again, this serves as an example of the text’s willingness to press buttons, to open wounds, to say the thing contemplated but never spoken. It leans heavily on pathos, true, but sharp wit and social awareness more accurately describe the work its doing. Emotion as power not weakness.

IXa.

still from Radiohead’s video for “Burn the Witch”

X.

Witch Hunt is haunted by the gaze of others. Being looked at, observed. Being seen. Being the center of attention. Wanting eyes. Needing eyes. Fearing eyes. Afraid of eyes. I don’t want to get all Lacanian on you, but how the narrator sees herself in relation to others constitutes a considerable measure of both her character identity and the narrative propulsion. Why? Because in this book the gaze of the other seems responsible for the introduction and resolution of conflict. The way others see the narrator seems to elicit the same effect on the narrator as an observer in quantum mechanics popping a quark and exposing either a particle or a wave, but never the two simultaneously.

Xa.

XI.

Men populate Witch Hunt more frequently, I’d wager, than any other topic. From rock stars to ex-lovers to current husband to father. But even so, these men seem to serve only as anchors for what so often turns into an exquisite revelation about the narrator herself. A perfect example of how this works comes on page 54 in the poem “Hanging from the Family Tree,” where the speaker says in the final stanza:

My father never speaks

Of his dead mother

Because

She used to beat him

When I asked one

Time what

She

Was like he described a

Woman

Who acted just

Like

Me.

Despite opening on the father, centering the father at the entrance of the poem, the father ultimately disappears after he serves the purpose of a springboard or jumping off point for what the poem really wants to explore and reveal, which is something about the narrator herself.

XIa.

still frame from Jerzy Kawalerowicz’s 1960 film “Mother Joan of the Angels”

XII.

Witch Hunt begins with sadness: the desire to disappear, and it ends in embarrassment: onlookers noticing the narrator’s red eyes. Between these poles we find a radical example of romance at the intersection of fantasy and apocalypse. You really must read this book. Even if I tell you all about it, you must experience it for yourself to fully comprehend the totality of Escoria vision. It only becomes alive when you run your eyes over it. Quietly, it awaits you.

Tags: juliet escoria, Witch Hunt