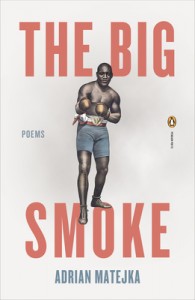

The Big Smoke

The Big Smoke

by Adrian Matejka

Penguin Books, May 2013

128 pages / $18 Buy from Penguin or Amazon

Mixed martial arts matches often descend into tussles, yet boxing remains a splintered dance: when you are down, you are out. The stripped-down bodies of boxers moving on the lit ring-stage is ripe for literary fetish; even Joyce Carol Oates, whose God is the unsentimental moment, could not resist waxing about Mike Tyson. Although Leonard Gardner’s 1969 novel, Fat City, chronicles the emotional and physical destruction of impoverished fighters in Stockton, California, he could not resist corporeal iconography: “Padded and trussed, his face smeared with Vaseline, a rubber mouthpiece between his teeth, he stood waiting while two squat men punched and grappled in the ring.” Sinewy syntax to represent a body ready to burst.

The same mythos allows Adrian Matejka to channel Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion. Matejka concedes that Johnson, in his own memoirs, was a “natural fabulist,” so fact matters less than emotion. But hasn’t it always in boxing? When Frank Bruno said he would knock Tyson onto Don King’s lap, no one believed him: except himself. The inches between boxers allow for miles of fantasy.

The same tendency toward fantasy makes many persona poems feel like projections of the poet rather than reconsiderations of the subject. Thankfully, Matejka resists pure fantasy and artifice; treatment of Jack Johnson is complicated and passionate. He appreciates his subject, much better than the analytical mode of much persona poetry, which makes the phantasmagoric act an exercise rather than an experience. From the start, his focus is on Johnson’s body: the tension between whether Johnson owns his own body enough to profit from it. It’s a smart take on the slavery that Johnson’s parents endured, and that he retains, in and out of the ring. In “Battle Royal,” the collection’s first poem, Johnson and other blacks fight for a single prize: “the last darky on his feet gets a meal.” Free enough to know what whites feared him, and to use that fright to complement his athleticism in the ring, but enslaved by a new system, where money creates identity, however tenuous.

This duality helps Matejka play on the concept of shadow boxing, with several dialogues between Johnson and his other self, one always chiding him for “Negro / caricature,” including his gold teeth. Those teeth are a light, a presence: power. From “Gold Smile”: “They call teeth dent in France, & the name / makes sense the way teeth do what they do / to bacon & shoulders & cakes. The French / word for gold is or, so when the folks in Paris / / describe my smile it sounds like what / happens when I punch a door: dents d’or.” The poem ends with Johnson’s taunt before the Tommy Burns fight: “the only reason I got gold uppers was to make / every bite of my food twice as expensive.”

Why box, if not for power? The entire schema of professional boxing is built toward narrative: a fight is contracted; training is daily, hourly; the weigh-in reiterates the importance of body; the slow walk to the ring peaks at the opening bell, and a frenzied battle follows. It is nearly impossible for a fighter to not feel bigger than himself at the conclusion of such a storyline. Despite the sport’s changes since his lifetime, Johnson remains the archetype of this sequence of hype and action, and yet even he had to earn his confidence in the ring. After boxer Joe Choynski knocked out a young Johnson during an unsanctioned bout, he is embarrassed: “His fists were so fast I’m still looking / for them.” Johnson is later homeless, sleeping under falling snow near Lake Michigan, and spending nights on the floor of a fellow fighter until “his no-good wife decided / to come back.” But in The Big Smoke, Johnson needs no favors. He knows that “hard work / is the only way,” which includes being “the one / fighter in Philadelphia / doing roadwork on / Saturday night,” including “calisthenics in the gas- / light.” The training enhances Johnson’s other self, and in the poem “Prize Fighter,” it makes sense that he compares himself to a horse, car, any locomotive element.

The only thing that moved as fast as Johnson’s fists was his mouth. While fighting Tommy Burns, “I bruised him with my right & talked / to him all the while.” “Mouth Fighting” explains the rules: you can rib a “fighter’s glass jaw, the cut / of his costume, the absence of pretty women / in his entourage.” Talking about mothers, wives, crippled relatives, or children is never allowed. In Johnson’s game, “as soon as I can tell he’s listening / I know I’ve won.” That same confidence allows Johnson to own his opponents. He “kept / [Stanley] Ketchel off the canvas . . . lacing him / just enough to bring blood for the show.” He pummels James Jeffries for fifteen rounds, the racist crowd unaware that “he was only standing because / I let him.”

But Matejka’s version of Johnson is not invincible. Like the men of Fat City, his weakness is not so much women–his abuse never lets them gain much power–but his constant need for control of women. The sexuality of boxing, is immediate, absolute. Nearly naked, aggressive, focused, boxers are offered to the public as is. In Gardner’s novel, Ernie Munger thinks about sex in boxing terms. When his wife refuses to sleep with him, “he wondered if he was adequate to her needs. One day he did two hundred consecutive sit-ups.” Johnson has no lack of sexual confidence in The Big Smoke. Like his early loss to Choynski, Johnson battles back from an early lover, Clara Kerr, the namesake of his left hook to the temple. Johnson’s first lovers were black, but his wives were all white. He taunts Hattie McClay from the ring and tells Belle Schreiber “as long / as you do what I tell you, / you get to cut a swath / with the Heavyweight Champion / of the World.” Matejka uses material items to show the pliability of Johnson’s power. His bout-won wealth buys him automobiles, but he can’t stop a police officer from removing him and Hattie from the car, slapping the seats with a club, while admonishing “Nigger, where’s / the chicken?”

It doesn’t matter if the incident is apocryphal or created wholecloth. Matejka is masterful at creating pointed emotions in blurred moments, as in “Out of the Bath,” when Johnson sneaks back into his hotel room to find the elegant and rich Etta Duryea singing, her voice sounding “like the water / dripping on marble, only with a breeze / pushing it.” Hattie is jealous, but a realist, aware that Etta “is society.” Etta’s later suicide is the penultimate poem of the collection, including Johnson’s discovery that she is “still breathing, whispering / a libretto on the heels of her last breath: / You did this, Papa. You did this.”

Earlier in the collection, Johnson’s shadow has a warning for the rising fighter: “You can change clothes / five times a day while / speaking Italian & playing / the viol in that fancy / classical way, but you / can’t change your skin.” White America’s fear was not that Johnson was different, but that “we are almost the same.” Jack Johnson loses when writers only consider him through the prism of race: when black characters are framed as not-white, then their selves exist only in a referential sense, they can never be individuals. Matejka’s version of Johnson contains more sides and selves than most creative representations. Johnson, more than anything, was a showman. His shadow self says: “You never wanted / to be a prize fighter. You just wanted the prize.” Matejka doesn’t need to include Johnson’s response, because The Big Smoke helps the reader, once and for all, to truly understand the boxer. We already know the answer: Yes.

***

Nick Ripatrazone’s most recent book is The Fine Delight: Postconciliar Catholic Literature (Cascade Books). He is also the author of two books of poetry, Oblations and This Is Not About Birds (Gold Wake Press), two forthcoming novellas. This Darksome Burn (firthFORTH) and We Will Listen For You (CCM Press), and a collection of short stories, Good People (Foxhead Books). He lives with his wife and twin daughters in New Jersey, and can be found at www.nickripatrazone.com

Tags: Adrian Matejka, nick ripatrazone, The Big Smoke

love that sweet science.

tinyurl.com/lr69xbu