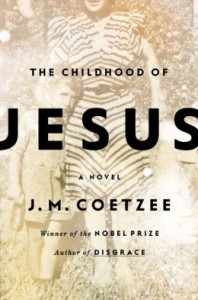

The Childhood of Jesus

The Childhood of Jesus

by J. M. Coetzee

Viking, Sept 2013

288 pages / $26.95 Buy from Amazon

As someone who has recently come to Australia, I find the reviews of Coetzee’s latest novel astounding. His early novels Life and Times of Michael K and Waiting for the Barbarians had readers and reviewers inferring the novels’ South African racial and historical specificities, with neither being identified in the books. Reviewers of The Childhood of Jesus, however, have mainly commented on the novels’ insular, literary and ageographical nature. Some reviewers have even gone so far as to say the novel is set in “an entirely Coetzeean universe” or a ‘Novel-land.’ Strangely, there has been an appalling lack of recognition of the book’s Australian context.

Reviews of most of Coetzee’s novels since he emigrated from South Africa to Australia have taken a similar tack. Many reviewers and critics have viewed his departure from Africa as being a departure from his usual themes of postcolonialism, nation and race. Coetzee’s speech given upon receiving citizenship seems to contradict this, with him saying very publically that in “becoming a citizen one undertakes certain duties and responsibilities.”

The Childhood of Jesus tells the story of middle-aged man, Simón, and young boy, David, who arrive by boat as immigrants in a Spanish-speaking country. Somehow in his previous life David lost his mother and on the journey to their new life Simòn vowed to help the child find her. Helped by the usual Coetzeean/Kafkan bureaucratic nightmare, the pair find accommodation, work and friends. In this new world, everyone seems to be an immigrant arriving by boat and none of them speak about their old lives.

Eventually Simòn finds a mother of sorts, Inés, for David and entrusts the boy to her care. Simòn continues to be heavily involved in the boy’s life and acts as a kind of teacher to him. David however is not a willing student and has entirely novel ideas on mathematics and language, getting him in trouble with school and eventually the state.

Reading Childhood during an election period shortly after I arrived in Australia may have made me more keenly aware of the novel’s Australianess. I appear to be almost alone in this thought though. After trawling through pages of reviews, I was staggered at the lack of writers connecting the novel to Australia’s current political and sociological position. A few reviews make the connection briefly but swiftly move onto discuss Coetzee’s high philosophical ideas.

One of the biggest areas of debate in past years in Australian politics has been the so-called “boat people”. Numbers of refugees arriving in Australian illegally by boat have dramatically risen in recent years – although the numbers are not big enough to warrant the size of the debate. Many of these are ethnic Hazaras fleeing Afghanistan (a country that Australia has a military presence in).

“Family reunions” is another hot topic in Australian politics. This is where refugees who are already within Australia apply to have their family members who have not yet escaped their country join them in Australia.

David and Símon’s story completely echoes these Australian zeitgeists, making it hard to view Coetzee’s novel as an exercise in purely literary and abstracted philosophical ideas.

The country David and Simòn emigrate to is indeed Spanish-speaking (leading some to believe it is a Latin American country). The novel, however, completely destabilises language. When David recites some German, he states afterwards that the language he just spoke was English. David and Simòn are not their original names but new ones they assumed in their new country – removing once more the signified from the signifier. One must also remember that, as with most of Coetzee’s recent novels, Childhood was first published in its Dutch translation. Then what is the original language of the text? Spanish in the novel is not the Spanish language from Spain (a country which itself is multilingual) but the idea of an unfamiliar language.

The descriptions we are allowed of the immigrants’ new home make it easy to see how this country is an allegory for Australia. It is a country where all of the inhabitants were at some point immigrants arriving by boat (it is generally believed Aboriginal Australian’s arrived by boat in Australia about 65,000 years ago). A country where there are huge uninhabited expanses outside of the main city on the coast. A country where David finds his fellow workers laidback and easy going. A country with an accommodating welfare system. A country where sport is valued extremely highly. Simòn’s first words in the novel are even “Good day” – dangerously close to Australia’s national greeting.

After recognising these connections, it begins to be hard to agree with Michael Duffy, in his review for The Millions, when he says ‘the dust jacket’s claim that The Childhood of Jesus is “allegorical” is misleading.’

Some reviewers have recognised that Coetzee is working on an allegorical level but have almost entirely, with a couple weak exceptions, failed to identify the allegory’s inspiration. Some mainstream sources have come close with Joyce Carol Oates commenting in The New York Times that the book is a ‘parody of a socialist utopia’ and The Guardian speaking of a ‘Coetzeean version of utopia’ without extending their scope to the island that Coetzee happily calls his home.

Childhood certainly addresses contemporary Australian issues of xenophobia and racism. The reluctance, even by Australian critics, to address this may reveal a resurgence of Australia’s cultural cringe but even if this were so there is a darker side to these omissions. Through ignoring this, we risk making Australia, and western countries more widely, into a no-place. The whiteness of these countries should not make them neutral, invisible and a haven from these issues especially when African novels are expected to naturally deal with these racialized and political problems. Australia needs intellectual probing and criticism just as much as South Africa and Coetzee provides this in Childhood.

To say that Childhood is engaging with Australian problems is not to say that the other literary and philosophical ideas are not also being discussed. It just seems that reviewers so far are neglecting a crucial element of the novel. To assume that when Coetzee left South Africa he left all political, sociological and racial ideas behind reveals a bigger framework of cultural and racial superiority. It is not Coetzee who has turned from these issues but the critics.

***

Daniel Rooke grew up in England and for the past five years lived in London. He recently moved to Melbourne, Australia.

Tags: Daniel Rooke, j m coetzee, The Childhood of Jesus