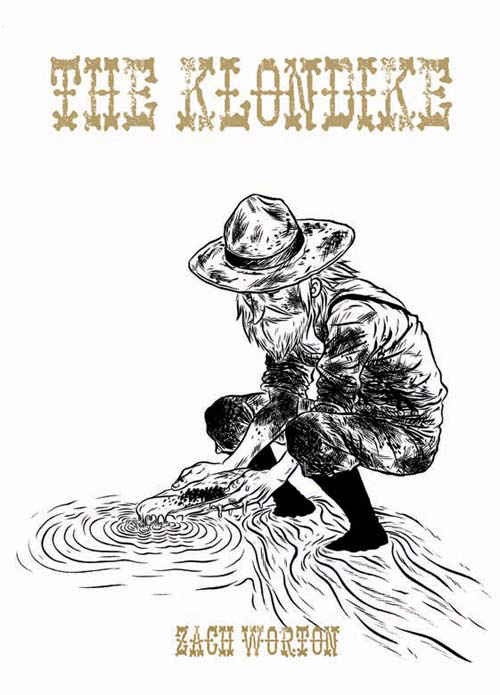

The Klondike is Zach Worton’s comic book (320pp, b&w, on sale now at Drawn & Quarterly’s website) about the Yukon gold rush. It’s historical fiction about a fascinating period of expansion, and it’s well researched. In an afterword, Worton talks about finding the right way to tell the story, which he figures to be about 80% accurate, and then lists a detailed bibliography for further reading. I’m interested in the way comics deliver narrative differently from prose, so I found the author’s note to be particularly interesting. The challenges are not disimilar.

The Klondike is Zach Worton’s comic book (320pp, b&w, on sale now at Drawn & Quarterly’s website) about the Yukon gold rush. It’s historical fiction about a fascinating period of expansion, and it’s well researched. In an afterword, Worton talks about finding the right way to tell the story, which he figures to be about 80% accurate, and then lists a detailed bibliography for further reading. I’m interested in the way comics deliver narrative differently from prose, so I found the author’s note to be particularly interesting. The challenges are not disimilar.

The first third of the book sets up all the characters and their objectives. These are in relatively short chapters. Because there are so many distinct people, I immediately thought that the book was going to be an encyclopedic look at separate historical figures, but before long Worton started to intertwine their stories. It was smart to establish things this way, because there are so many actors in the book. It’s like a Shakespearean history, in that it’s very easy to get lost with all the who’s-who.

The book starts in 1878 with George Holt, the first white person to traverse the treacherous Chilkoot Trail. That’s his only contribution, but it’s an important one. Later the story chronicles how difficult all travel was in the Yukon. The mounties would forbid people to cross if they didn’t have enough supplies. There was an avalanche that killed dozens of people. They only turned up, horrifyingly, after the thaw. Another route, called the White Pass, featured an area called Dead Horse Gulch, because, well, that’s obvious. Boats, too, were wrecked and in every case there were opportunists to capitalize on their misfortune.

One such opportunist was Jefferson Randolf “Soapy” Smith, a despicable con-man whom Worton treats harshly, portraying him as a fork-tongued hypocrite of George W. Bush proportions. The book ends in 1898 with his death. Smith (who “pioneered” the “soap with a prize inside” con that comes up several times in Deadwood) had a shootout with Frank Reid. Reid was Smith’s opposite, a strong public servant. He was killed in the fight, too, though it took him twelve days to die. The penultimate pages of the book are of their gravesites; Reid has a tall monument, Smith’s was paltry. Worton notes that Reid’s funeral was the largest the area had seen, which makes me wonder why Soapy Smith is the one who is celebrated today. We love our ne’er-do-wells.

My favorite character in the book was Charley Anderson, who got hoodwinked into buying a useless claim for an exorbitant price; he worked it hard and became a  millionaire. George Carmack was noble — he befriended the Tagish natives when everyone else was too racist. Belinda Mulrooney was a fearsome, strong woman hotelier. She says this great line: “I don’t want to be the richest woman in the Klondike. I want to be the richest, period.” Charles Constantine, a Mounty, was strict, selfless and good. I guess I liked all the hardworking, decent people and loathed the crooks who stymied their progress, because at the frontier, people are the base of humanity. However, Worton notes that he didn’t want the book to be about good vs. evil, just about these characters. As such, he leaves the other levels to work for themselves, and that’s the hallmark of good storytelling.

millionaire. George Carmack was noble — he befriended the Tagish natives when everyone else was too racist. Belinda Mulrooney was a fearsome, strong woman hotelier. She says this great line: “I don’t want to be the richest woman in the Klondike. I want to be the richest, period.” Charles Constantine, a Mounty, was strict, selfless and good. I guess I liked all the hardworking, decent people and loathed the crooks who stymied their progress, because at the frontier, people are the base of humanity. However, Worton notes that he didn’t want the book to be about good vs. evil, just about these characters. As such, he leaves the other levels to work for themselves, and that’s the hallmark of good storytelling.

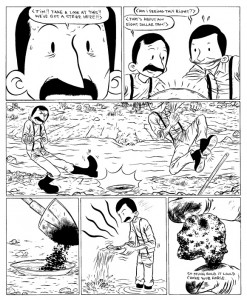

Worton draws people with hard lines and he draws the landscape with a lot of cross-hatching. This does a lot to show the wildness of the landscape, but it’s hard to keep all the personages straight. To this end, Worton does a good job separating them by the shape of their mustache or hat. He places an illustrated cast-of-characters at the end; a glance at it shows how much he relies on a cowlick to distinguish a prospector from a Mounty from a journalist. There are 25 main characters listed there. How impressive is it to be able to draw that many people so that they are recognizably different? It boggles my mind, especially when I think about how everyone was wearing the same clothes there — dark pants and button-down shirts and hats and suspenders and heavy coats. Sometimes Worton’s style distracts from the story, though. Like, it’s weird to see cartoonish legs mid-run (ie. comically akimbo) when I’m sensing the actual, panicked urgency of the story. But no matter, that, because this historical fiction was ready for the graphic novel format and I can’t envision a better looking account than The Klondike.

love the phrase “comically akimbo”

good review

I liked reading this.

I was huge into comics for a long time and would like to get back in. The trouble is I am angry that drawing does not come easy to me (I thought I would be a cartoonist before I decided to be a writer) and that finding an artist to work with is so nearly impossible.

thanks for this. More writing on comics please HTMLG!