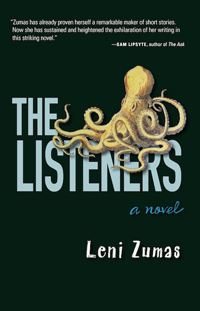

The Listeners

The Listeners

by Leni Zumas

Tin House, May 2012

352 pages / $12.95 Buy from Tin House, Amazon

When loss is central to a novel, its author faces the unique peril of either fixing the loss—after which there is not much of a story—or dilating it, foregrounding it, and even praising it so that it becomes habitable for a reader. The absence has to be wildly present if it is to be effectual, and the character experiencing it has to be enjoyable enough for a reader to stay with her as she grieves, reassembles herself, or falls abyssward. Leni Zumas’s The Listeners is a novel whose narrator, a thirtysomething bookstore manager and former singer named Quinn, orbits around the loss of her younger sister. Zumas’s effort to preserve that loss is stunningly successful. She reveals Quinn to us in circling episodes, deftly holding the character in the form of a smear of selfhood who doesn’t want to be entire.

The condition of completeness is impossible in Quinn’s world. Since her sister’s death decades ago, she’s been only part-person, and ghost-heavy as the story she gives us. A damaging spectacle of protracted grief, Quinn’s narrative is open enough to let us see her vulnerability and temporally broken enough to get us to believe that her words belong to time itself, which doesn’t care about chronology. There are moments when Quinn acknowledges in interior monologue that she isn’t whole or capable of experiencing herself wholly. For example, in an early scene in which she and her brother Riley are walking to their parents’ house for dinner, she says, “As usual I imagined the destinations of strangers to be firmer than my own. They all had real places to be, where real things happened.” But it’s mostly the angularity of Quinn’s narrative that establishes her fragmented nature. Restless, it drags us back and forth between three periods in Quinn’s life. The first of these is Quinn’s childhood, the era when she loses her sister to a freak bullet. In the second era, as a young woman, Quinn is mostly on the road with her band. The third era, the present, is incomplete, tumescent as it is with pasts.

Eras collide without much notice, though sometimes there are typographic cues that let us know a voice (either Quinn’s own or somebody else’s) from the past has infected the present. In the following scene from the novel’s first page, the italicized type represents an exchange between Quinn and her sister:

In childhood passages, Quinn suggests that she, her sister, and her father have Nabokov’s affliction, synesthesia. For instance, when Quinn describes herself learning to play guitar, she says she “tried to play with songs [she] liked but couldn’t and it sounded like a field of circles with tiny black dots.” About her sister, she says “She worried about pimples, but not about the shapes and scents flying around in our heads. We got born lucky, she believed, able to see things in a way other people couldn’t. But I did not want to see them that way. I wanted to be regular, like Riley, who hated when we talked about what color a number was, or a sound.” Because of Quinn’s synesthesia, often what’s most important in her experience of the world is the color and sound of things, the semiotic haloes that are apparent to her but to us are just the spaces between aspects, effects, and hints.

Given the experiential shifting, dissolving, and linking that it allows, synesthesia is effective in helping us understand Quinn’s fixation on less explainable connections. Throughout the novel, there’s a conceptual relationship between menstruation, loss of virginity, and death. All blood in Quinn’s memory comes from both what she calls the “downstairs” and the hole in her sister’s head. In one instance, as a teenager she finds blood on her underwear and sheets, then hides the discovery and linens from her parents. She says, “I kept the bag of stained cotton in my closet for three days until it was trash night, and waited until [Dad] had dragged the laden can to the curb before running out with my secret bag and stowing it at the very bottom, under the grinds and shells.” Without guidance for us, Quinn finishes the passage by saying, “A bullet, depending on its angle of entry, can cleave the striations of a muscle in such a way as to trigger profuse hemorrhaging that is difficult, if not impossible, to stanch.” Conjoined incidents, the period and death are sites of intense reverberation; the color from one merges with the other, and then neither is recognizable on its own.

There are superstitions too. In an early scene at the bar where Quinn’s former bassist, Mink, works, Quinn talks with a young patron who recognizes her from the old days. “So this is totally weird,” he says, “because I just saw another guy from your outfit. And now I see you.” As the boy goes on to describe this other member, Quinn realizes and denies to herself that it’s Cam, her band’s drummer. Fearing his return, she nervously snaps the therapeutic rubber band that she wears on her wrist. Several pages later, in the same setting, she says she wants to tell Mink and Geck, the band’s guitarist, about her conversation with the boy who spotted Cam. She wants them to assure her that “it could not have been Cam he saw—that Cam lived in California, in Brazil, in the Alps for god’s sake and was certainly not riding any subways around here. But I kept thinking about that old sorcery rule about saying people’s names out loud. How it brought them back.” Indeed, for most of the novel, Quinn doesn’t say her sister’s name, which suggests she fears her return even more than Cam’s.

Like the sorcery rule, the bloodworm that Quinn frequently alludes to is a fantastical thing. It is a “worm who eats blood and is made of blood,” a childhood phantasm that moved “in and out of [her] sister’s holes.” It’s come back to induce pathologies like obsessive-compulsive counting and starvation. In anticipation of a family dinner, Quinn explains that the worm’s return is concomitant with Cam’s reappearance:

Quinn believes that the worm disappears if she stops eating, a tactic meant to halt her menstruation. “I goaded a small bite onto my fork,” she says during the dinner scene. “Two more made three. Six more made nine. If I only ate nine, the worm couldn’t come. Worm you are banished. Stop and breathe, the good doctor had said. When you start counting or listing, fill your lungs with air. But if I breathed, I would eat, and if I ate, the blood-logged worm would come sniffing.” The number three is one of Quinn’s prominent fixations; it represents to her a kind of resolution. When she counts, she counts by threes; the story she tells is made up roughly of three eras; there were three siblings before the sister died; there were three months between the sister’s first period and her death. These heaped threes make the number necessary and final to her. It seems that through severe self-avoidance, she even wants to bring her family down from four members to three members. She is the would-be completing casualty. Her choices are either that or bring her sister back to raise the family’s number to five, safely removed from three.

But until the last page, The Listeners is a book of ghosts, not resurrections. There is the ghost of Quinn’s sister, and also Cam’s ghost, which might be newly reified if we believe the boy at the bar. But there’s another important ghost; his name is William Faulkner, and he haunts each page of The Listeners. Quinn shares with Faulkner’s narrators an aspectual way of telling and revealing. Narrating with both sound and fury, she introduces us to the effects of trauma (more ghosts) and then explains the trauma itself later.

When we first encounter the sister, she’s only a “her” whose stuff is still in boxes in the family basement. And 100 pages into the book, Quinn introduces the death:

And even later in the narrative, a fuller explanation:

In a section about Quinn in high school, she impassively examines The Sound and the Fury’s Quentin Compson’s tormented relationship with his sister Caddy’s sexuality: “The main character in the book we had to write a paper on was obsessed with his sister, kept thinking of her while he got ready to drown himself. The sister wasn’t dead as far as I could tell, but the book was confusing; she might be dead. Or was she just a slut?” She goes on to talk about her essay questions for the book, and these might as well be a way into The Listeners. The first is “How does the novel’s narrative structure engage questions of time and memory?” and the second is “How does the sister’s absence act as a presence?” Quinn is several of the Compson siblings: She has Benjy’s associative ricochets, Quentin’s obsessed torment, and Caddy’s waywardness and sisterly care. In each incarnation, her grief answers the essay questions. But Quinn’s understanding of time provides a more important connection to The Sound and the Fury. For her and the Compsons, time is a sensation or a texture. Time isn’t just imbued with memory; time is memory, and all new experience is reconstituted trauma. And with horror Quinn recognizes that she’s pitched toward a future that can only be made less ghastly by allowing the past to complete itself, to come back when she says its name.

***

Jared Woodland lives in Los Angeles.

Tags: jared woodland, leni zumas, The Listeners, Tin House

I thought this book was very cool. I would have liked to see a bit more about Quinn’s development as a vocalist, and how it interacts with her peculiar sensory issue, but it was amazing anyway.

[…] Jared Woodland reviews Leni Zumas’s The Listeners for HTML Giant. […]