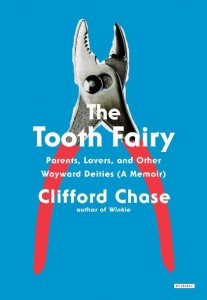

The Tooth Fairy: Parents, Lovers, and Other Wayward Deities (A Memoir)

The Tooth Fairy: Parents, Lovers, and Other Wayward Deities (A Memoir)

by Clifford Chase

The Overlook Press, 2014

256 pages / $24.95 Buy from Amazon

Clifford Chase’s The Tooth Fairy begins with an epigraph, a line from a James Schuyler poem: “Out there/ a bird is building a nest out of torn up letters.” And this is Chase’s task in The Tooth Fairy, to weave a home from fragments of thoughts, memories, journals, dreams, and song lyrics, each ribbon and twig twisted with the other ribbons and twigs, until the strands form dense architecture, a story that holds one close.

At first, it seemed The Tooth Fairy would be an exhausting read. In the first chapter, an essay partly about the extraction of molar #30 from the author’s mouth, each of the fragments—which meditate on everything from blood oranges to antidepressants to sexual confusion—are, with few exceptions, a single sentence long. I’m a reader with an affinity for books made of fragments—I adore Barthe’s A Lover’s Discourse, Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation—but I wondered if I could keep up. The sentences leap swiftly from image to image, subject to subject, developing few of the connective strands. The images are at turns funny (a fat little dog with a plastic steak in its mouth), and at turns lyrical (clouds are “golden cloth with a purple sheen”). My mind felt a little jet-lagged. Chase was building this nest from such small twigs. But the warp and weft of the first chapter continued into the second, and the nest began to grow.

Each chapter considers a different time in the author’s life: a trip to Egypt with his partner John, a period of sexual confusion in college and afterwards, the deaths of his parents, a strange luggage mix-up. And each chapter has its own narrative arc, a central focus for meditation. There are strands, too, that connect each chapter to the next: Chase worries, suffers guilt, attempts to be a good son, partner, and brother, loses family members, loses part of his city, loses his sense of himself, loses love. He gains things, too—understanding, occasional connection. The book is full of emotional punches.

The Tooth Fairy invites one to seek patterns, and some of the fragments can be sorted into categories, one of which could be labeled “meta-fragments.” In these, Chase often considers or directs the reader about how the white space between fragments is working. In one instance, Chase writes that the white space represents “the gap between the part of [himself] that was happy with John and the part of [him] that wasn’t.” In the final chapter of the book, “Ken,” Chase reconsiders his brother, who died of AIDS in the late 1980s and whose death is the subject of Chase’s earlier book The Hurry-Up Song. In The Tooth Fairy, Chase has acquired Ken’s journal, and uses Ken’s writing and interviews with Ken’s friends to gain a multifaceted understanding of his brother. In this chapter, Chase tells us that the white space represents “several months in 2009 and 2010 of trying to absorb and understand [Ken’s] suffering.” Here, the gaps between fragments represent time and thought and sorting. In another chapter, Chase tells us that he assembles these “simple, factual sentences” in an attempt to “make the past seem almost comprehensible—not normal exactly, but closer to it—that is, an objective story I can view without shame.” This proclamation is followed by three such sentences, each of which speaks simply and literally, and also hints at a narrative iceberg sleeping beneath the surface:

“Superman was a turn-on.

The basement used to flood regularly.

The pipes froze.”

In all of the white spaces, the reader (and maybe, too, the writer) builds a narrative while also accepting that there is no perfect, comprehensible narrative, no perfect answers to Chase’s questions. Each sentence stands like a tooth in a mouth, perfect on its own—an independent unit with root, dentin, and enamel—yet rooted and most functional alongside the others.

There’s a fixation on connection and disconnection in this book. Sentences are linked to each other across white space as people are linked to each other across the gaps between our psyches and our bodies. In a particularly moving moment, Chase is driving with his father, who is in his nineties, while Chase’s mother is in the hospital with a broken hip. Chase’s father uncharacteristically breaks down. As he sobs in the passenger seat, Chase has a moment of discomfort, but then is “able to say to him, simply “I know, Dad” and to reach out and pat his shoulder” (158). And that’s it—a touch on the shoulder, and Chase’s recognition that his father needs to cry, and to know that his sadness is recognized. In that tiny touch, the white space between son and father is momentarily breached.

This fixation on connection takes a surprising turn in the chapter “Lost Luggage.” Chase’s mother has died, and Chase, still grieving and bewildered, takes a trip to Germany. After his return flight, he finds strange items in his luggage: a plastic bag from a shoe store in Tehran that contains sheet music and Persian costumes for children. Chase begins a seemingly futile search—absurd, even—for the owners of the lost items. The connection Chase makes here isn’t one I expected, but it lifts him, however briefly, out of his grief.

And then, there is sex, with all its divine connections and awful disconnections. In “As If” Chase recalls the confusion and sadness, as well as the joy, that made up his on-again off-again relationship with a woman, dubbed “E,” when he was in his twenties. When things were good between Chase and E, the two were fast friends, spontaneous and playful, and Chase seems enamored with E’s beauty. But these good times are separated by moments of cruelty, uncertainty, rejection, a lot of tears, and erotic dreams about the men in Chase’s life. Chase quotes his own journal from the time in which he calls sex a “roller coaster,” but in dense, lyrical fragments he also captures the transcendence of physical sensation when sex with E was good. Of these times, he writes: “I was like a cell accepting her, another cell, right into my protoplasm” (120). And this, it seems, is the craving that haunts The Tooth Fairy: the longing to merge completely with another, which is, of course, impossible but for the briefest moments.

***

Shena McAuliffe is a PhD Candidate in Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Utah. Her stories and essays have been published in Black Warrior Review, Conjunctions, The Collagist, and elsewhere. She is the nonfiction editor of Quarterly West.

Tags: Clifford Chase, Shena McAuliffe, The Tooth Fairy

What do tooth fairies drink when they are thirsty. Find out in The Trooth And Nuthin But The Tooth A Fairy Tale coming soon