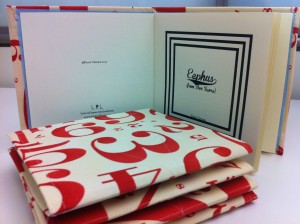

Eephus

Eephus

by Kevin Varrone

Little Red Leaves, Textile Series 2012

$8 Buy from Little Red Leaves

[Begin with this.]

I did not know what a fungo was until I read Kevin Varrone’s Eephus. This chapbook introduces names and facts in a way that makes you feel whomped, but there is little flexing in all this whomping. The expertise that builds this book never feels “built up” or leering. Pause. Appreciation. Reflection: when people build up an expertise, it so often snowballs into an authority that drives off listening. Not Varrone. Not Eephus. This poem is not a statistical rant. It’s not even sports writing. It’s an almanac. The best kind: the kind of almanac that comes out of Philadelphia.

Eephus sticks to the course of tumbling lyrical investigation—it’s all graces and hushes and subtle goofs. The weight of a baseball (5.25 oz) gives way to meditations upon the wait of baseball, bound together as the avoirdupois of the game (“time passing is pretty much what baseball is all about”). Waiting: for the bullpen to get warm, for the streak to end, for DiMaggio to roll over, for Ryan Howard to heal up.

The book by no means breaks in continuity from Varrone’s earlier work, which has been called a Philadelphia trilogy. Pausing to ruminate over the city plans, Varrone observes that the city itself looked like a baseball diamond in its original conception.

So what’s a box score?

It might be a personal cartography of the game, a language with dialects peculiar to whoever is holding that little pencil. In Varrone’s case, this particular scoresheet merges into the portraiture of a city he has dedicated years to graphing. Varrone points us to a painting by Morris Kantor that sets the elevation from which the poem observes all the positions.

As a fan, Varrone followed the way of Lenny Dykstra, starting with the amazing Mets and then leaving town to join their division rivals. By virtue of this same flexibility, Varrone easily sidesteps the milieu of ESPN (and its manufacture of fast-talking nicknaming inside-ness) to write a poem about baseball that sounds nothing like Scott Van Pelt (thank God). The book is knowing and broad-minded, considering things outside of the game with the same reverence with which it attends the Phillies. It even offers some film criticism. In this way, the book feels like a reclamation project, pulling the game out of the jaws of SPORTS and making it a part of other things, a thing in line with other things, a work, an art, a set of rules, a fortune cookie, a historical site, an ancient language, an oracle and etymology.

As a fan, Varrone followed the way of Lenny Dykstra, starting with the amazing Mets and then leaving town to join their division rivals. By virtue of this same flexibility, Varrone easily sidesteps the milieu of ESPN (and its manufacture of fast-talking nicknaming inside-ness) to write a poem about baseball that sounds nothing like Scott Van Pelt (thank God). The book is knowing and broad-minded, considering things outside of the game with the same reverence with which it attends the Phillies. It even offers some film criticism. In this way, the book feels like a reclamation project, pulling the game out of the jaws of SPORTS and making it a part of other things, a thing in line with other things, a work, an art, a set of rules, a fortune cookie, a historical site, an ancient language, an oracle and etymology.

The argument that baseball is held back by purists, that the game is too long, that it must be modernized, never explicitly enters the poem, but it seems to lurk in the poem’s consciousness (“when I’m sure there is nothing going on I step inside”), the eephus doubling as a kind of bouncing ball begging for attention. America’s pastime is desirous of your attention. In the words of Kevin Varrone, baseball is “ a place where there is a meadow,” the kind of empty space that allows for slow motion. The poem Varrone spins from the permission of this man-made meadow is one that needs to be heard. It’s a special kind of pastoral that feels equal parts Roman (Varro) and Philadelphian. In this sense, this game is unmanaged, in strict contrast to the world of sports (“to remain substance in the face of transubstantiality”). Varrone occupies that meadow in his poem and brings us to Hejinian, Oppen, Olson, Duncan, Dickinson. The unblinking openness of baseball that is its special avoirdupois, the massive weight of time that fills this poem up, that recommends the consciousness operating through the writing. Varrone’s many returns to the meadow bulk up the field of the poem and leave little doubt that the author has a lot more than baseball on his mind.

At times, the book sounds sociological, but not like Ken Burns. Varrone plays radio baseball and the verve of his transmissions and announcements would sustain this book through 200 more pages. Reading Eephus, it becomes pretty obvious how much fun it is to turn the knob, rolling from from Harry Kalas to Kevin Costner to Jimmy Rollins to Winston Churchill and Emily Dickinson. A roving we will go a la “O’Brien to Ryan to Goldberg!” Here’s a video dedicated to the author of Eephus, out of gratitude for writing a poem about baseball and poetry and movies and Philadelphia and Big Papi and birds and night games and announcers and shortstops and Roy Hobbs and maps of where words come from. This is a book best heard through headphones.

***

Kevin Varrone is the author of passyunk lost (Ugly Duckling Presse), id est (Instance Press), and g-point Almanac, 6/21-9/21 (ixnay press) . He is the recipient of a 2012 Pew Fellowship in the Arts and lives outside Philadelphia.

Paul Klinger received his MFA from the University of Arizona and his JD from the University of Houston. He serves as an editor for Little Red Leaves. His most recent chapbook is Jumblefate (Dusie 2011).

Tags: Eephus, Kevin Varrone, little red leaves, lrl, Paul Klinger, textile series

[…] http://htmlgiant.com/reviews/the-way-you-enter-history-a-review-of-kevins-varrones-eephus/ […]