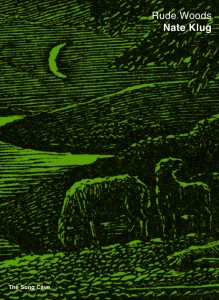

Rude Woods

Rude Woods

by Nate Klug

The Song Cave, 2013

76 pages / $17.95 Buy from The Song Cave or SPD

In his Deformation Zone, Johannes Goransson writes of the nature of translation saying in the process of rewriting a text “the ‘meaning’ may have been ‘lost’ but the materiality of the text is brought to life.” Nate Klug, in his latest book Rude Woods (The Song Cave, 2013), embodies this type of translation at its most intriguing and productive. Eschewing the constraints of a strictly “faithful” translation in favor of a more multifaceted dialogue with Virgil’s Eclogues, Klug himself becomes one of the lyrical shepherds he invokes as he responds to the Eclogues which are themselves, he writes, “poems about responding—listening, picking out, and answering back the pleasures of song.” Klug’s brief examination of each of Virgil’s original ten eclogues offers a contemporary take on the pastoral tradition that brings to life both Virgil’s lyric refinement and dynamic content.

Most refreshingly, these are not your mamma’s frilly little nature poems. The pastoral as an idyllic scene is revealed as artifice; in its place the earth as complex, fraught, psychic landscape is shaped. Here, Virgil-via-Klug becomes a sensual experience in the most dynamic way as it invites readers into physical observation of and participation in the environment while invoking, as W.R. Johnson states in the forward, a “severe concentration on emotion [that] determines these poems’ unique form.” Take a moment to experience the following lines:

from “A Hymn to Prophecy” (from Eclogue IV):

“wool will never have to dye: for the rams / will trick their fleeces, from boiled-saffron-yellow / to the deep purple produced by shellfish juice.”

or from “Against Epic” (from Eclogue VI):

“even this young orb called earth, / spinning dry, hardening, until things slowly / owned their own forms.”

or, lastly, from “Two Longer Love-Songs” (from Eclogue VIII):

“I saw you once and was lost. / Something wrong and warm carried me off.”

What we get here are emotion-driven images, but they are not grounded in the typical poetic gesture “I emote therefore my poems have gravity.” Instead, they are vivified by the transformative power of sensual detail. Not only are “wool” and the “earth” and the “you” brought to life for us as readers through the uniqueness of their portrayal, but the portrayal itself is metamorphosing—”Right there in the field, grazing lambs will go red” (from “A Hymn to Prophecy”).

But I must admit initial skepticism. A moment of strong lyricism will get my attention but often for the wrong reasons. The lyric, as many writers and readers know, has a tendency to overindulge. An emotive, senses-based series of poems about love and loss and shepherds singing in a flowery pasture could be a hotbed of disastrous pitfalls. But what Klug does well is interrogate these tropes and traditions even as his words participate in them. He creates tension by restraint—not through expected thematic or plot-drive narratives but through the imagistic and sonic qualities of the language itself.

In his translator’s note, Klug refers to this quality as “the rough music I sought”; it is “rough”—and “rude” and bitter and bruised. It is also imbued with a “sweetness” and beauty that, in moments, startles with its clarity of vision. It is this complex “song” that ushers forth the unexpected, “unnatural” environment of the new pastoral, a landscape that becomes less of a tangible place of sheep and shepherds, and more of a conceptual space in which sensual experience serves as the landscape itself.

Rude Woods does at times feel burdened by these heavy underpinnings. The overarching structure of emotional registers spoken through sensual detail may feel exhausted by the end of the text. Yet Klug makes brilliant self-referential moves to address the process of finding balance in these lines. On the whole, he takes his own advice (via Virgil) to maintain a fascinating lightness, an ethereal quality, that he writes of in “Against Epic”:

“A shepherd should keep the flock fat but his lines refined, like exquisite thread.“

There is indeed a threadlike fragility to these poems; there is also, to continue this metaphor, a strength in how tightly woven the poems are through their imagistic and sonic complexity. Though there are moments when the translation may feel too heavy handed, Johnson is right when he notes, “most translations of the Eclogues attempt to reflect the original’s intricate language with some variety of high style. . . Klug has devised a conversational idiom that relies on spare diction and spare syntax, on a pure clarity of sight and sound to give us superb poems that give Virgil’s pure lyricism a genuine ‘answering form.'”

By the close of the text, we have been privy to a complex and dynamic series of contemporary translations that pay homage to Virgil’s intentions while reaching interestingly beyond the bounds of the tradition from which they arise. As the prophet-poet rightly tells us in “A Hymn of Prophecy”:

“It’s here, the beginning, or the end of everything, / as the Sibyll has sung; time for the great order / to start over . . . the insurgence of a new kind of human being.”

***

Jessica Comola is an MFA candidate at the University of Mississippi where she serves as poetry editor for the Yalobusha Review. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Anti-, Redivider, and Everyday Genius, among others.

Tags: Jessica Comola, Nate Klug, Rude Woods