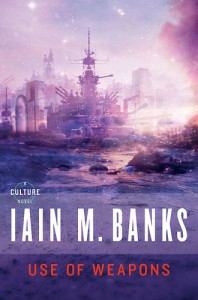

Use of Weapons (Culture Series)

Use of Weapons (Culture Series)

by Iain M. Banks

Orbit; Reprint edition, July 2008

512 pages / $15.99 Buy from Amazon

The Culture series by Iain M. Banks just keeps on getting better and in Use of Weapons, the narrative takes on added complexity in a two-pronged narrative that intertwines the tale of a hunter, Zakalwe, who has left the Culture and a woman, Sma, who still works for them. I’d go so far as to say this is one of the most experimental works by Banks, or for that matter, any science fiction writer, particularly in light of the ending. Because of its added intricacy, I (PTL) invited Joseph Michael Owens (JMO) and Kyle Muntz (KM) to collaboratively review the book and share/debate/spur our thoughts in a “cultural” exchange.

Peter Tieryas Liu: What was your take on Zakalwe and Sma in the pantheon of Culture characters?

Joseph Michael Owens: To be honest, Cheradine Zakalwe and Diziet Sma are probably two of my very favorite Culture characters overall, and I’m currently reading the last book in the series. The chemistry between them is truly fantastic. It’s hard to explain without giving away major spoilers, but you’ve got a really fantastic setup where you can see there is a great detail of history between them and it’s 100% believable. You can feel that they know each other incredibly well and, in some situations, they’re really the only ones that can handle each other.

Banks is also good with layering characters’ roles, and you get the feeling that both Zakalwe and Sma have done and seen a lot that doesn’t necessarily have to do with their current occupations, which I love. I think it adds an extra human element to the characters, these two specifically, because we’re shown that they exist — and have existed — outside of this single narrative. And since they feel like people and thus read like people.

The ending is . . . it’s just wow. . . .

Kyle Muntz: I’m not sure I can add too much to Joe’s comments (since I think that’s totally on-base and right), but in retrospect, I’d say Diziet Sma in particular has really stuck with me. The Culture series has a lot of strong female characters, but Sma is definitely one of the most interesting and best realized. For me, one thing the experimental elements of the novel call attention to (by telling Zakalwe’s story forwards and backwards at the same time) is how broad life is; and how separate different episodes in it can be. Especially when the chronology is destabilized. The novel gives glimpses of the same people, years apart–and each time they seem different, sometimes almost unrecognizable. And that’s life.

Use of Weapons is the last Culture novel to focus on a small cast of characters. After this, it becomes a sequence of vaguely Pynchonian ensemble pieces, and while I love the broader scope that brings to the series, it makes me appreciate the more intimate characterizations of the earlier novels, especially this and Player of Games. Characterization wise I think Banks is in top form here. In general, every Culture novel is unique, but formally none of them stand apart as strongly as Use of Weapons.

PTL: One of the most interesting chapters is when Banks’ describes Zakalwe’s first time aboard a Culture ship, Size Isn’t Everything. It’s our first real exposure from the eyes of a newcomer to how different the Culture is from everything we know, particularly with a post-scarcity economy in which anyone can do what they want.

One of the dialogues I remember is a waiter who talks about what’s important in life and why he enjoys wiping tables when he can do anything he wants: “I could try composing wonderful musical works or day-longer entertainment epics, but what would that do? Give people pleasure? My wiping this table gives me pleasure. And people come to a clean table, which gives them pleasure. And anyways, people die; stars die; universes die. What is any achievement, however great it was, once time itself is dead?” What do you guys think about the Culture? Things you like and dislike?

JMO: I remember Banks saying once that he modeled the Culture off of his ideal utopia, which is kind of cool because that’s an example of the power of writing and creativity: you can literally create your own world, and then go play in it! There’s really nothing I dislike about the Culture; I’m like the ultimate Culture fanboy. The way I’ve read it since book 1 (Consider Phlebas) is that a pan-human race created AIs that were able to perpetuate and evolve themselves into the Minds we know and love in current Culture novels. The AIs basically take care of all the mundane activities for humans so that humans can dedicate themselves to whatever they want: art, recreation, education, various experiences in general. Disease has been eradicated in the biological citizens, and people can augment themselves any number of ways they desire for utility or for fun. This sounds totally like a place I’d want to live!

KM: There’s a certain amount of tension within the novels about the Culture, mostly questioning how such a powerful, secular, completely free, post-violence, post-scarcity society (controlled entirely by machines) should interact with violent, oppressive, warfaring societies who rule themselves and do a terrible job of it. But I think the Culture is objectively pretty perfect.

I read the series over a year ago now, but it was the setting that kept me coming back: the Culture, endless, unchanging, as a place to live and way of life to be explored. Genre fiction tends to treat society as something to be moved: societies fight war, are saved from corruption, whatever. Which I’ve always thought was boring, and pushes me away from series like Song of Ice and Fire. Instead, the Culture is basically incorruptible and one of the most intellectually sound utopias in fiction. (Another good example is Triton by Samuel Delany.) There are elements of the setting I still think about pretty regularly, and in retrospect even echo through a novel I wrote called The Holy Ghost, which was about a utopian-ish society that did have to deal with scarcity.

Another main tension is always going to be that the Culture isn’t run by people — it’s run by machines infinitely smarter and, yes, more humane than we’ve ever been. This isn’t something I’d want to dive too deeply into, other than to say: I don’t really see the problem.

PTL: The contrast between the Federation (e.g.) in Star Trek and the Culture is fascinating in that while both are postscarity, the latter embraces human nature to an extreme while the Federation espouses a future in which human nature is transcended. Sma is casual about her sexual liaisons with crew members and all hints of traditional morality are banished, whereas in the Federation, conservative values are still very prevalent. But the biggest difference is that the Minds run the Culture whereas the Federation has a council that is susceptible to corruption. So in that sense, the Culture could not exist if it weren’t for the Minds and Artificial Brains that are in control. Beychae, the target of Zakalwe’s chase, poses an interesting thought: “The Culture believes profoundly in machine sentience, so it thinks everyone ought to, but I think it also believes every civilization should be run by its machines.” Zakalwe replies: “I have no idea whether they’re the good guys or not… They certainly seem to be, but then who knows that seeming is being? I have never seen them be cruel, even when they might have claimed they have an excuse to do so. It can make them seem cold, sometimes. But there are folks that’ll tell you it’s the bad gods that always have the most beautiful faces and the softest voices.”

In some ways, these “Artificial” Minds are the future gods, albeit quirky and eclectic ones. Do you think there’s an assumption by Banks that humans can’t achieve this totally peaceful society by their own means and need someone else in control? For all practical matters, if there were a master species of aliens that were also benevolent, they could easily take the place of the Minds in the fiction (though that probably would have been harder to swallow for human readers who would equate it to human slavery).

JMO: I like the Minds-as-future-gods idea because to us, they would be, especially given that they (i.e. the Culture) are a level 8 civilization. However, there are also level 9 and 10 civs out there (10 being those civs that have Sublimed, if I recall), who are ostensibly gods even to the Culture and other level 7-8 civs. This is something you are even given an example of in the final Culture novel, The Hydrogen Sonata, when one Mind talks to another that has actually returned to “the Real” from the Sublime (something that is almost unheard of).

Also, I got this from a wiki: “Also significant within the Culture novel cycle is that the book shows a number of Minds acting in a decidedly non-benevolent way, somewhat qualifying the godlike non-corruptibility and benevolence they are ascribed in other Culture novels. Banks himself has described the actions of some of the Minds in the novel as akin to “barbarian kings presented with the promise of gold in the hills”.”

I think the idea is that, once Sublimed, you are fully actualized within the greater universe. One of the feelings you get, however, is that Subliming is something civilizations also do when they — for lack of a better term — get bored, and decide simply to “retire.”

To go with your main question, I think as long as there is a sense of “us” and “them,” or more specifically, “the other” — and as long as there are resources that are not available to everyone — it will be incredibly hard for humans to achieve such a totally peaceful society by their own means. Humans are inherently opportunistic, even when they have the best intentions. As long as someone else has something you want, you’ll likely experience some level of envy. Oftentimes the sense of envy will be manageable, but what happens when it’s not, i.e. in situations where what you want involves feeding starving people? Of course that’s a base need versus simple want, but when resources become scarce, the line gets blurry.

KM: ^(What Joe said.)

Also, though, I do think it’s notable that Bank’s utopia represents such a progressive politics. SF has a reputation as being progressive, but I’m not sure that’s really the case, and it definitely wasn’t back in 1987, when the first Culture novel came out. Despite its tendency to push intellectual boundaries, there’s an alarming militaristic strain that that runs through SF even today — and I sort of see the Culture series as a refutation of all that.

PTL: Just curious Joe, but do the Sublimed civilizations get featured more in future installments?

JMO: Yeah, it’s actually something that gets referenced a lot and comes into play in more than one novel going forward.

PTL: In terms of humans being inherently opportunistic, do you think that’s part of the “culturation” and can be modified in a society where concern for resources are eliminated like in the Culture?

JMO: I don’t know . . . I mean, I don’t want to sound negative on humans, but I think it might be encoded into our DNA. For example, if you look at the gap between humans and chimpanzees — two species that share a lot in common when it comes to being opportunistic — and you stop to think about how the gap between humans and the A.I. Minds is exponentially greater, it’s almost a total stretch to think humans could get there on their own. The only route would seem to be engineering that particular trait out of our code (a la eugenics), and that’s of course posed its own set of problems, historically. Humans just give me the impression, looking at their track record and protracting it back evolutionarily, that opportunism is an everlasting trait.

KM: I wish I knew the answer to this. I think Schopenhauer had us right for the most part (we’re like black holes that eat our own lives and our universe, and at the center is a sort of emptiness that’s never filled), but at the same time, that’s not something I like believing. The problem is I think human behavior is so dependent on circumstance it’s difficult to generalize in any effective way, but if the circumstances were right I’d like to think it could happen.

PTL: Hey Kyle, I’d love to hear you elaborate more on the militaristic strain you see in current SF. I know some of the post-WWII science fiction had that tendency, as we can see in writers like Heinlein (who, in his defense, also fought against the insanity of the Nazis). The Culture’s approach to military is fascinatingly utilitarian but, at times, can seem unusually cruel because of it’s calculating nature (as in Consider Phlebas). At the same time, Use of Weapons makes this interesting observation by Sma: “In all the human societies we have ever reviewed, in every age and every state, there has seldom if ever been a shortage of eager young males prepared to kill and die to preserve the security, comfort and prejudices of their elders, and what you call heroism is just an expression of this simple fact; there is never a scarcity of idiots.”

KM: Man, this is a great question, and one I doubt I can answer well, so all I can do is stick to some general impressions. There are a lot of criticisms leveled at science fiction and fantasy, and most of them I disagree with, but I think what bothers me most about the genres (as they’re commonly practiced) is that their narratives, essentially, tend to be drawn out setups for big battles — even if they aren’t jingoistic or whatever. And at the center of the narrative spectacle is a sort of glorying in mass violence, at that space where reason and values break down and people just have to kill people.

This is a problem even with less conventional writers, not just Martin but China Mieville, Dan Simmons, and even to a certain extent Steven Erickson (who Joe and I are reading right now and really enjoy). I’m always a little bothered when these complex, well-realized, artful stories become setups for hundreds of pages of these big boring battles. And what bothers me most is the narratives sometimes seem like excuses for the battles.

At least for me, the best and most interesting SF doesn’t follow this pattern, but a lot of it still does. It’s something I’m always glad to see the genre move away from, and Banks takes huge steps in that direction with the Culture novels, both when it comes to how stories play out and in their general ideology.

Also, I’m always glad to see science fiction or fantasy that focuses on the personal, rather than the macro-levels of society. Banks achieves a pretty much perfect blend of that, so just a another thing to add to the list of reasons he’s awesome.

PTL: You know, I never thought about it in the light of most narratives being excuses for battles. But when I think of many of the classics, they always do lead to a penultimate conflict with the whole galaxy at stake. Say Ender’s Game and Dune to name two. Banks fights against that trend- even in Excession where the final battle is almost anti-climactic. What do you both think it is about his writing that you think helps create that “perfect blend” that, honestly, in a less skilled writer’s hand, would not have worked?

KM: Yeah, I’d say Banks definitely writes books with high stakes for lots of people, but mostly the Culture novels are about how to avoid mass violence, rather than narratives that ultimately give into it and accept it as necessary or even natural. It’s one of the main themes of the series for me, and one that gets explored in lots of ways, especially with the shadow of the Idiran War hanging over everything.

Banks does a great job balancing that with strong prose, interesting ideas, and doing it through human (or inhuman) stories where the spectacle is more than things just getting blown up. I think Banks wants to impress people with how awesome his universe and the things in it are, rather than how awesome it is to see them destroyed, which for me is a pretty important distinction.

PTL: The eclectic cast of characters in the Culture series include the religious Idirans, the game-crazy Empire of Azad, and a whole gallery of worlds in Use of Weapons. At times, Banks will throw in a random paragraph describing an alien, a ritual, a passing observation, that in some ways could be the basis of a whole story or novel in itself. One of my favorite scenes is when Zakalwe’s head gets chopped off and he’s describing the experience as he sees his body detached from the head. Later on, as they regrow his body, the drone gets him a hat as a present, which perfectly summed up both the drone and the strangely thoughtful and humorous Culture.

Who are some of the characters that stick out in this one?

JMO: Diziet Sma, for sure! I really love that the universe Banks has created is tightly interwoven (yet so enormous) that there’s very little overlap, very little that repeats between books. I think this gives the series a connected, yet vast feeling, and when a character makes a cameo in another book, it’s such a cool thing and Sma is a perfect example of this!

Sma is first introduced in a collection of stories called The State of the Art in a novella that’s eponymously titled. In the novella, the Mind in charge of an expedition to Earth (c.1970) decides not to make contact or intervene in any way, but instead to use Earth as a control group in the Culture’s long-term comparison of intervention and non-interference. The tone is much lighter than that of Use of Weapons, but you see a lot of what makes Sma so great in the much longer work. Chronologically, TSotA takes place and was written before UoW, but I read them in the opposite order.

KM: I can’t comment on the characters as well as I’d like, but for me, I remember thinking that on a certain level, especially later on, the Culture novels really do function as galleries of things, people, and ideas — and it almost always works. Banks is [JMO: should we (sadly) say “was?”] an intensely inventive writer, and he stayed that way for all ten of these books. And even at the end he was still going strong: The Hydrogen Sonata, the most recent (and tragically, final) has a 10,000 year old man who codes memories into his skin; another who covers his entire body with penises; moons that orbit beneath the surface of their planets; ships that dance [JMO: fleets of them!]; a holy book in which, somehow, every word is true.

There’s a sort of consistent, endlessly interesting invention in Banks that I don’t think many other writers can match. And even though the focus, tone, and subject matter of each Culture novel is very different, this is something that stays consistent throughout the entire series.

PTL: I don’t know if anything can compare to a man who covers his entire body with penises, ha ha. [JMO: I haven’t gotten to this guy yet; I’ll be on the lookout!] I also love the unique locations Banks uses as the backdrop — Use of Weapons covers a lot of geography, as in the concept of the city that keeps on changing: “He drew a secret satisfaction from this inchoate permanence, and did not hate going there as much as he pretended.”

One of the more interesting points for me in Zakalwe’s life is when he tries to be a poet and give up his mercenary ways. “It had always seemed to him that the ideal man was either a soldier or a poet.” But when faced with the violence of the overseer, ripping out tongues of slaves who tried to escape, he reverts back to his old ways. How important is that struggle internally between the poet and soldier within him, and what do you think it says about his character that he gives up on being a poet pretty quickly? The Culture espouses the idea that both go hand-in-hand, but that duality seems to escape Zakalwe and his leaving the Culture is, in many ways, a commentary on the singularity of his convictions.

KM: Yeah, for me the Culture series is also really about the set-pieces. They just keep getting more awesome as the series goes, really.

Again, I can’t comment on Zakalwe’s character as well as I’d like, but considering the choices he made (ultimately he can’t give up violence, and particularly mass violence), I don’t think it’s any surprise he chose to leave the Culture. He’s the exact opposite of what the Culture is about.

Most of Bank’s characters tend to be outsiders to the Culture, which makes sense because, especially over the course of all the books, it allows you to see things from so many different perspectives. Zakalwe’s character really capitalizes on that, and it seems important how Banks continues to capitalize how vast a thing a society is, and how deeply changed it can seem when viewed from different perspectives.

PTL: The ending just blew me away. I can’t remember the last time a story felt like it just ripped out my guts and threw everything I thought I knew out the window. The dual narrative structure made perfect sense once we reached the end. It completely recontextualized the story and gave a new brand spanking new layer of gravity to Zakalwe’s choices, including his decision to abruptly join the Culture after leaving it as well as his futile attempt at being a poet. Is there any way we can talk about this without spoilers? I don’t think so, so here’s a big SPOILER alert as we’re going to talk about the final reveal. Did either of you guys see that coming? There are definitely earlier references as in an early flashback when he talks in his sleep about: “a great metal warship, becalmed in stone but still dreadful and awful and potent, and about the two sisters who were the balance of that warship’s fate, and about their own fates, and about the Chair, and the Chairmaker.” But I never once suspected that Zakalwe was not actually Zakalwe.

JMO: There’s something to be said about cliched maxims like “my own worst enemy” and “no one can hate me more than I hate myself” that we’ve seen in so many books. What happens to Zakalwe is a complete and utter break from reality and a detachment from his past, so significant, he’s literally harboring so much anger that it manifests itself as an alter ego. (I’m trying to process this; it’s just such an intense ending! . . . ]

PTL: I completely agree and it really gets you looking back on his entire life. I don’t know if the ending would have been as powerful if we hadn’t first seen his life in flashbacks which makes us very sympathetic to his journey. The whole time, we think he’s escaping his past, and in a sense he is. But whereas I thought his anger was directed at the Chairmaker for the horrible act he inflicted on his sister (thereby causing his disillusionment and the haunting guilt that chases him wherever he goes), we find out that it’s the reverse, explaining his self-destructive behavior at the end as well as his military genius. It makes the line, “Memories are interpretations, not truths,” take on a whole new light, and I like how all these different elements are connected by his relationship with the Culture.

JMO: But the best part of all the Culture books, I think, is that each new one tries to do something new and fresh within the universe. While it’s not always quite as successful, Banks gets an “A” for trying. It seems like he could’ve just done something similar to the first couple books again and again, but instead he chose to give the readers even more of a view of his wonderful universe. Big props!

KM: I was pretty fascinated by the formal elements of Use of Weapons. It’s not experimental in the sense of being especially difficult, but it’s somewhat unique in that it capitalizes on experimentation in order to add to narrative rather than detract from it. But yeah: pretty difficult to talk about without spoilers.

PTL: Overall, where would you place Use of Weapons in terms of ranking it? I’ve read the first four so far (up to Excession) and this is my favorite. I’d also recommend either this or Player of Games be the first book Culture fans should read, even though Consider Phlebas is probably a better introduction.

1. Use of Weapons

2. Player of Games

3. Excession

4. Consider Phlebas

KM: My ratings are kind of weird and vague, but for me it would be:

1: Player of Games

2: Excession

3: Look to Windward

4: Hydrogen Sonata/Use of Weapons

5: Matter

6: Consider Phlebas

7: Surface Detail

JMO: I’d probably rate them as follows, though I should mention I wouldn’t rate any of them below 4/5 stars. (I just really love this series!):

1) Use of Weapons

2) Consider Phlebas

3) Excession

4) Look to Windward

5) The Player of Games

6) The Hydrogen Sonata

7) Inversions

8) Surface Detail

9) Matter

10) The State of the Art (novella)

If you’ve read this far, the three of us salute you! We’re hoping to tackle Excession next as the Culture gets ready for war with one of the most brutal and savage races ever described in science fiction.

***

Joseph Michael Owens is the author of the ‘collectio[novella]‘ Shenanigans! and has written for [PANK], The Rumpus, Specter, HTML Giant, Grey Sparrow & others. He is also the blog editor for both InDigest Magazine and The Lit Pub, and you can find him online at http://categorythirteen.com as well. Joe lives in Omaha with four dogs and one wife.

Kyle Muntz is the author of Green Lights, forthcoming from Civil Coping Mechanisms in early 2014. More recently he’s also the writer and designer of The Pale City, an independently produced RPG for PC.

Peter Tieryas Liu is the author of Bald New World (Perfect Edge Books), Dr. 2, and Watering Heaven (Signal 8 Press). His work appears in places like Hobart, Indiana Review, McNeese Review, and the New Orleans Review. He ponders literary weapons at tieryas.wordpress.com.

Tags: Culture series, Iain M. Banks, Joseph Michael Owens, kyle muntz, Peter Tieryas Liu, Use of Weapons

[…] http://htmlgiant.com/reviews/use-of-weapons-by-iain-m-banks/ […]

[…] If Use of Weapons was a psychological investigation into the world of the Culture, Excession is a philosophical excavation, featuring the AI Minds going to war. The Culture have come across an ancient artifact that is “a perfect black body sphere the size of a mountain” and a “dead star that was at least fifty times older than the universe.” Its disappearance and reappearance decades later spurs off a string of events that make for one of the most frenetic, entertaining, and metaphysical science fiction narratives I’ve read. Joining me for this review of the fourth book in Iain M. Banks’s Culture Series are Joseph Michael Owns and Kyle Muntz in our followup to our Use of Weapons review (which was at HTMLGiant). […]