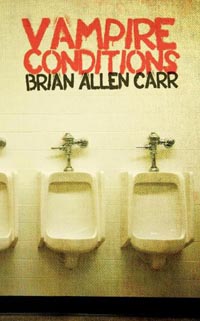

Vampire Conditions

Vampire Conditions

by Brian Allen Carr

Holler Presents, 2012

114 Pages / $9.99 Buy from Amazon or Powells

When given the choice, I mostly choose not to read literary realist fiction. I’ve been out of school for more than a year now, so I’m accustomed to having the choice. I read Brian Allen Carr’s collection Vampire Conditions anyway, and I loved it. I knew that I wanted to review the book, too, which meant that I would have to find a way to articulate why I loved it. There are two keys. First, Carr takes nothing for granted. Second, he never justifies his stories.

Carr’s refusal to take anything for granted makes him different from most writers of literary realist fiction because most of these other writers — the ones I now choose not to read — will resort to writing what they think “it’s really like” when they aren’t sure what to do next. That is to say that they often make boring events and characters (affairs and the middle-aged people who have them, unconsummated affairs and the middle-aged people who don’t have them, cancer deaths and the survivors who mourn them, suicides and the people who commit them, drugs and the people who use them) and congratulate themselves for writing the world the way it is. This takes the reader for granted because it assumes his or her interest will sustain itself without the writer’s help. This takes the world for granted because it suggests that the way we expect things to be is the way they are. Such writing fails as an imitation of reality; nothing in this life is ever much like what it’s “really like.”

I don’t believe that Brian Allen Carr writes his literary realist stories by asking himself what is likely or real. If he were doing it that way, he wouldn’t have made up Thick Bob, a grotesque who one day gave a bartender so much shit she actually tased him — and who, when he saw how much pleasure it brought the bar’s other patrons to see him tased and collapsed on the floor, proceeded not only to continue antagonizing the bartender, so that she would regularly repeat that performance, but to mount brief shows on a small stage inside the bar, wherein said bartender hits him with a bat, explodes fireworks in his clothes, throws darts at his person, and etc. If Brian Allen Carr wrote stories by asking himself what is likely, he wouldn’t have invented the protagonist of “Lucy Standing Naked,” a young boy of Asian descent, adopted by white Texans, who is named Nelson, and who is learning to play the guitar, and who sings country music better than most white boys, and who is in any case a novelty because there’s never been a famous country singer who looked like him. He wrote Nelson because Nelson was interesting. He wrote Nelson because Nelson makes a good yarn.

What I mean when I say that Carr never justifies his stories is that I do not believe they are designed to be fair to anyone involved. (Nor are they pointedly unfair.) No one gets what they deserve, because no one deserves anything, and thank God; I am so exhausted with reading all about deserving people. In a story that begins with a miscarriage, he writes of the un-child’s father, “Barrow didn’t know whether or not babies went to heaven, but he wished a minister was there to tell him they did.” The father has not lost his child because he is a bad person or because he had an affair or because his wife was a bad choice for him or because he once hurt a girl he doesn’t know anymore. He has lost his child because it gives us something to feel about, and because it gives him something to feel about also, which gives him a way to be a person on the page. What I am describing here is “narrative,” which isn’t necessarily moral or perverse, and which doesn’t require an intellectual agenda to justify it, because what happens in a story doesn’t need justifying. It (narrative) is the most satisfying thing in fiction. It is also the thing that most people can’t be bothered with.

So when Nelson’s father meets George Straight’s brother in his (the father’s) capacity as a butcher, and when Nelson’s father tells George Straight’s brother all about his talented performer of a son, and when Nelson’s father gives George Straight’s brother extra steaks in order to win his sympathy, and when George Straight’s brother agrees to see Nelson play, with the expectation being that a sufficiently good performance would lead to a record contract then stardom then wealth, I don’t feel as if any of this is happening because Nelson has suffered, because he is unpopular at school, because he is not especially bright, or because he was adopted. (“I didn’t get mad at my mom when she told me I was adopted on my twelfth birthday. Mainly because she had already told me on my eleventh birthday. And on my tenth birthday. And on my ninth. On my eighth birthday, though, that time was different. That time I cried and cried.”) If there will be a record deal, then this is not a reward for the bad things Carr has put him through. If there will be no record deal, then this is not a punishment for what Nelson secretly thinks of his father. It will only be the next interesting thing to happen in a fascinating story. And this is all I need.

I am reminded, sometimes, in reading Carr, of the many twists and turns of Barry Hannah’s stories, and the surprising sentences he found along the way. The stories in Vampire Conditions are concise, condensed variations on those loose, wild structures. But in each story’s few pages, Carr also finds room for surprises, and wildness of his own. Here are three surprises: “She couldn’t let one of her fallen brother’s heroes stay that way. In a saloon in Corpus Christi watching his final finger float.” . . . “My friend had a little pier and beam house with a fence that was rotting, and he put me up in a back room, went off to work and dropped a barrel on his head and died.” . . . “White folks never dedicate their cars to loved ones.”

I didn’t have to read the stories in Vampire Conditions, and I read them anyway. If that’s not enough for you, then I will say this: they are generous but unsentimental, strange but never proud, thoughtful but not too thoughtful, with good sounds and sentences you won’t see coming, not because they are contrived but because they are not yours. They are better.

***

Mike Meginnis has published fiction in Best American Short Stories, Hobart, The Collagist, The Lifted Brow, PANK, elimae, Booth, and many others. He serves as prose editor at Noemi Press and co-editor of Uncanny Valley with his wife, Tracy Rae Bowling, and writes text adventures with others at exitsare.com.

Tags: Brian Allen Carr, mike meginnis, Vampire Conditions

“I don’t believe that Brian Allen Carr decides writes his literary realist stories by asking himself what is likely or real.” copyeditor…Nice review though, looking forward to reading it!

This was one of my favorite books of 2012.

Yeah that bugged me too, but ironically I can’t fix it because I didn’t actually make this post. :/

fixed!

<3