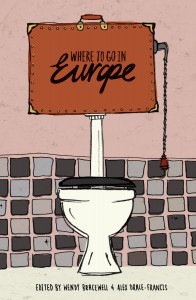

Where to Go in Europe

Where to Go in Europe

Eds. Wendy Bracewell & Alex Drace-Francis

UCL Publishing Horizons, 2013

120 pages / $4.99 Buy Kindle on Amazon

Life seems to be an enterprise of attaching meaning to arbitrary artifacts and rituals, which seem themselves to embody something called ‘culture.’ I don’t think there’s anything immaterial to culture—it’s just how humans have lived and live now. We all have bodies which are (and have been) largely the same, but different cultures craft different rituals and habits, for whatever reasons. This doesn’t seem to mean anything, inherently: it simply is.

This book, then, is a short and delightful anthology of writing about experiences with foreign toilet technology, for lack of better phrasing. Aside from how interesting the book is as an exploration of people trying to “make sense” of intercultural experiences, it’s a delight to read because of the plethora of voices it contains: there’s an almost-voyeuristic pleasure to reading, say, Andrei Pleşu‘s account of an encounter with a highly-advanced Japanese toilet, or Savkovič’s description of going to a Bulgarian festival with a Belgrade model. The slim volume deftly creates a patchwork of different experiences, ranging from puerile to poignant, not imposing any critical framework on the reader but simply asking her to marvel at and revel in the complicated range of human emotion and expression that is available for topics like toilets, urine, and feces.

Not having such a framework is a modest decision, which makes this book very likeable. Like culture, it simply is: its economy is immediately appealing, and the irony of reading it while in the bathroom is, against all odds, delicious. Most importantly, built on the premise that we all need to evacuate our bowels and bladder, yet in so many different ways, Where to go in Europe presents a more important commonality: everyone judges everyone else for how they use the bathroom, in different ways. Everyone has not individual bathroom rituals and ideas of what a bathroom should be, and the bathroom is a crucial site for exploring our own cultural biases. To me, it’s somewhat interesting that this topic is so often explored in the context of humor— Žižek’s “toilet ideology” bit, David Foster Wallace’s “The Suffering Channel,” and ‘oodles’ of other somewhat-scatological postmodern stuff —as if, in trying to analyze the abjection of the encounter with bodily waste, ‘western’ analysis itself succumbs to revulsion, and must ‘laugh to keep from crying,’ as it were. Can we ever escape ideology? Is trying to imagine life outside ideology absurd?

Hard to say, but another pleasure of this text is that, while provoking such questions, it points to this class of questioning as absurd: instead of imagining hypothetical utopias, we should ‘air the dirty laundry’ of ideology, so to speak, and look frankly at how it is always operating through us and around us. Becoming more aware of ideology isn’t necessarily freedom from it, but it might afford some level of critical distance, in the same way that meditation asks us to simply, nonjudgmentally stay in the present, observing thoughts passing like clouds in the sky of the mind. The editors include an excerpt written by Giuseppe Baretti in 1770 where— in reaction to travelers like Sharp who generalized about all Italians based on the filth of Naples, in which, at the time, people urinated and defecated, it seems, at liberty —he writes about the stench of Madrid, and how it drove him to end what would have been a month-long trip and “be gone, and never think to see this town again,” but that he “will not blame the Spaniards for having suffered this evil to increase upon them age after age in such a manner, as to be now almost past remedy…”

Baretti considers staying— for these are the choices the traveler has, to stay or to go —but “cannot endure the thought of satisfying [his] idle curiosity at the price of a month’s torment.” He admits, though, that: “Long custom to be sure will reconcile any body to any thing…” It seems like traveling is an essentially sensory experience, because other cultures cannot be understood, they can only be lived, through “long custom” that rehabituates and recontextualizes the body. Traveling, then, is not an encounter with “other cultures,” it’s an encounter with novel sensory experiences, and for travelers to generalize from that is a great mistake. The options are to partake in the sensory experience or not, and in the case of bathrooms, the only thing one encounters besides bodily waste is one’s own emotional reactions to the sensory experience, which are filtered through one’s own ‘culture,’ that is, one’s own “long custom” regarding the handling of bodily waste.

from David Černý’s Entropa (2009)

The text includes an excerpt from Kapka Kassabova‘s Street Without a Name in which the narrator’s mother, after having endured Bulgarian public toilets her whole life, which “were the ante-chamber of Hell,” visited Delft with the narrator’s father, on a study visit to Holland. Her mother entered “the sparkling, perfumed, pink-toilet-papered, flower-arranged, mirrored, white marble toilet of Delft University, clean as a surgery theatre, gilded as an opera hall, bigger than our apartment in Youth 3, and she cried.” It is this, the narrator says, and not the “supernaturally clean streets” and other accoutrements, that “tipped her over from stunned awe into howling despair.” One’s ‘identity in culture,’ so to speak, is only a series of habits, the “long customs” Baretti talks about, and, bereft of the material context in which to perform one’s usual habits, the traveler experiences something perhaps comparable to the confusion of trying to imagine being human without having language.

If we suppose that culture is the ways people live, then technology plays a fundamental role in defining culture. The Turkish-style hole that the Bulgarian mother is familiar with has nothing to do, inherently, with Bulgaria. But “long custom” turns it into a symbol for her nationality, and humans, probably thanks to language, live in mostly-symbolic realms. All of the material and ritual that comprises culture offers potential sites of imagined ‘cultural difference,’ and this book offers a thoroughly-enjoyable and thought-provoking look into some of the discourse surrounding the politics of piss and poop. As a good book should, it leaves you wanting more.

***

Manuel Arturo Abreu is a writer based in Portland and NYC, with more work out at natrices.tumblr.com and twigtech.tumblr.com.

Tags: Manuel Arturo Abreu