X

X

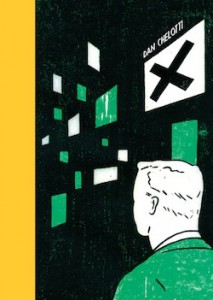

by Dan Chelotti

McSweeney’s, 2013

82 pages / $20 Buy from McSweeney’s or Amazon

Equidistance is a matter of perspective. The Say It with Writing salon where I found Dan Chelotti’s debut poetry collection X is located midway between the rising North Avenue Arts District and Baltimore’s shabbily-mortared potter’s cemetery. Chelotti’s row house poetry is right at home between art and death. Short, but with a long back; and bald, but with a yarmulke of hair on his crown, the round-faced Chelotti is also a greedy one for transition words: I was thinking this, but then that happened. Welcome to the X. It’s what horse people call a cross, and what Italian horse people call a cavaletti. It’s the Bowie Knife mark you cut to suck the venom from a snake bite. It’s the way you remember where you buried those doubloons. It’s the man who preached about getting active against a context that won’t budge.

Like an associative poet, Chelotti uses more images than statements, but two thirds into most of his poems he places a hinged joint, a transition, and he uses very different associations to get out of the poem. “Thoughts over Foreign Sandwich” begins with a Swedish uncle cooing over the speaker. The speaker identifies with the “elderly contortionist” and wonders if he could have a new name, a Swedish name, “I would be Per. / And being Per, I would / adore calculus.” At the point where the poem is almost becoming too precious, Chelotti bangs us with his transition: “But dammit, / I don’t love calculus, / I don’t even know / what calculus is.” The poem argues against mere concepts, “My desk is a trap / into which I fall— / hands first” in favor of something more sensual.

Chelotti’s hinges are subtle. Most of his transitions would be lost in poems with stanza breaks, which may explain why he doesn’t have any. X contains sixty-two poems on seventy-nine pages without a single instance of “meanwhile, back at the ranch” or “let me come at this again” which a new stanza offers. Chelotti doesn’t even put his poems into sections so that the reader has a place to rest and absorb the arcs. Why? Because there are no arcs. These poems are one endless link of boxcars on a train that doesn’t have a whistle or a peg of rust. Chelotti’s writing is clean and tidy enough to pull this off. Consider the opening third of “Augury”:

been there to point out

the axles of my carousels,

to let the dead know

what I’m up to.

Take the day

I stuffed my car with boxes.

I was very sad. I thought,

if only someone could

remind me how to feel.

I got in, started to drive

and a swallow flew

off the back of my head.

Here, Chelotti wrestles with old adversaries—intellect and emotion—before finding his way to an irrational, but believable conclusion. The pace is slowed down; he doesn’t like to get out of second gear in any of these poems so that in spite of each poem feeling like a tiny apartment the reader isn’t constantly fiddling with his oxygen tank to get more air.

Block-like poetry which doesn’t feel claustrophobic? I think this writer may be onto something. Most poems need a twenty-minute shower. Chelotti writes like Lady Macbeth, scrubbing out the stains. The knobs are so polished you can see yourself. Which is partly the point. These are personal poems, not of experience, but meditation. The speaker is not the engine, rather, the moment drives these poems. The speaker is merely a fellow passenger, one of us.

It helps to think of these poems as a series of odes, not to Grecian urns but to moments of life with faint wrinkles in them that change everything. The on-ramp is often a premise drawn from life such as “Migraine Cure” which begins “The rain says, Listen to Debussy, / go ahead, Debussy will fix you. / But the rain is a liar.” Chelotti’s transition happens sooner in this poem, but that’s the beauty of it, especially because this poem has two of them. Otherwise, we wouldn’t quite grasp the urgency of the ending:

if he were alive, I would buy him

a milkshake and say, Here, Desmond Dekker,

it’s malted. He would smile

and tell me to believe in myself

although at times I am

Arjuna on the field of the soul.

I wouldn’t understand everything

through his patois

but I’d understand what I’d have to:

the sweetness of the milkshake:

the saltiness of the fry

we are only alive for a short while.

First book collections should be more about an author’s reach and less about his mastery. There’s a lot of promise here, and that’s quite enough to forgive an author who sometimes gets things a little too clean that some of the soul goes out with the bathwater and sends the poet reaching for moons a little too often to bring it back. I suspect that Chelotti is already sorting this out, and figuring out how to write about a moment without using the word when. “Every poem needs to fail in the middle,” Chelotti said that night, meaning exactly the opposite, since all of his succeed at the X of a poem, it’s cross, it’s place to jump, where “I fell in love. I danced again.”

***

Barrett Warner gets kicked for a living at his family’s An Otherwise Perfect Farm where he breeds, breaks, races and buries horses. He is also the poetry editor of Free State Review and his essays also appear in Rain Taxi, JMWW, Concho River Review and Coal Hill Review.

Tags: Barrett Warner, Dan Chelotti, X

tinyurl.com/l3cselt