Roundup

Sunday Reading List

Over at The Rumpus, Elissa Bassist offers great advice on how to write like a funny woman.

The National Book Critics Circle has announced the finalists for their 2011 book awards.

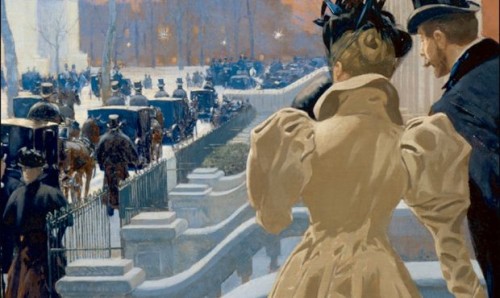

Edith Wharton turns 150 on Tuesday and she still looks great. The New York Times gives her a nod as they talk about heiresses and social climbers and such.

Anil Dash discusses the web as a medium for protest.

On her blog, Anna Leigh Clark shared an image of the most amazing writing group that included Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Ntozake Shange, June Jordan, Lori Sharpe, and Audrey Edwards, among others. I want to know absolutely everything about this group now.

Margaret Atwood revisits The Handmaid’s Tale, which has remained in print since 1985.

Cory Doctorow’s essay about a vocabulary for speaking about the future is really interesting.

Are you watching Downton Abbey? Team Mary, right? And Edith; she is the worst. Over at The Millions, an essay about the literary pedigree of the show. Also, Shit the Dowager Countess Says and Downton Abbeyonce. You’re welcome.

Jennifer Weiner looked at the gender breakdown for reviews in the Times for 2011.

In The Atlantic, Caitlin Flanagan wrote a… curious essay about Joan Didion that included the assertion that to really love Didion, you have to be a woman. Like I said, curious.

Tags: Downton Abbey, Margaret Atwood, toni morrison

I can’t believe you omitted your own amazing piece at Salon: http://www.salon.com/2012/01/20/the_anger_of_the_male_novelist/

jesus, that didion article. in order to love didion (to be a woman) you have to love clothes? curtains? what about sex, benzodiazepines, music, war, cars, sunlight, backyard swimming pools? ughhhh flanagan, what a way to put on those male-colored glasses and call didion ‘chick lit’

I was pretty appalled. Those things are well and good but it’s so dismissive of Didion’s body of work to suggest that’s even remotely what her work was about. I keep trying to write some kind of response but I get stuck at, “What the fuck are you talking about?”

Flanagan made her ‘conservative’ bones asserting that feminism betrayed women because it/they – feminism; feminists – militated against nurturance and, in particular, against any women devoting themselves to domesticity.

–so: a Straw-Fightin’ Lady, inveighing against emotive but childishly inaccurate caricatures.

With Didion, one gets, of perception, the instrument and the object: say, this Californian woman and (some slice of) Californian America. Her foregrounding of herself as a sensing instrument–a lens or antenna–is neither “extraordinarily introspective” nor “extraordinarily narcissistic”. One gets, from Didion’s journalism, memoir, and Play It As It Lays, impressions of the world, which therefore are impressionistic worlds, more or less phenomenologically astute . . . but outwardly oriented. The pressure Didion records is not a hermetic fantasy, but rather, interactive with to-me recognizably intersubjective experience.

–in contrast to Flanagan’s subject(s): Caitlin’s discontented malice. (“[T]he Didion-Dunnes had one of those […] marriages that children have an impossible time breaking into.” Ew. “I never wanted to tell you about all of that.” Meta-ew.)

I’m actually going to–and believe me, I never thought I would type these next words–agree with much of what Caitlin Flanagan is saying. I don’t think you have to be a woman to recognize and appreciate Didion’s masterful writing or to truly be a fan, no. But there aren’t many female writers who are taken as seriously as she is and who write about things that speak to women without being “women’s issues.” (Like, I had no idea she cut her teeth at Vogue.) But, yes, the girl-in-her-bedroom vibe, the internal questioning written in this crisp, brittle, unapologetic way, the extraordinary self-doubt spoken with such skill: These are things I think women writers feel more than male writers, because they go hand-in-hand with so much of “the female experience” (insofar as there is one).

I dunno–she’s an icon, and she’s an icon to me as a writer and a woman, and there aren’t many writers who achieve that status. There are many female writers I admire, but few who reach that iconic status–for me and for other writers, including men. When Flanagan called her “our Hunter S. Thompson”–sort of a pat comparison, but overall, yes, that’s it. Women appreciate Thompson too, but there was something essentially male about him that went beyond the fact that he was a man/writing about “man things.” I feel the same about Didion.

Also: SYBIL! Team Sybil all the way. Except for the costumes, where Mary totally wins.

I was really disappointed in Flanagan’s article on Didion too. I’ve never read anything by Flanagan before, so I wasn’t expecting so many WTF lines like The second reason Metcalf was left flat by this line of reasoning is

that he isn’t a woman, and to really love Joan Didion—to have been blown

over by things like the smell of jasmine and the packing list she kept

by her suitcase—you have to be female, and She was our Hunter Thompson, and Slouching Towards Bethlehem was our Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. He gave the boys twisted pig-fuckers and quarts of tequila; she gave us quiet days in Malibu and flowers in our hair. No. Just no.

Also: I’ve never watched Downton Abbey but now I feel like I’m really missing out.

I love Sybil too! So much sass and independence.

I feel like two people tell me Flanagan is crazy every day now. That’s . . . that’s some intense market saturation, right there.

Ha! Did you worry about a lightning strike when you found yourself agreeing with Flanagan? I very much agree that Didion does something special in how she writes about things and experiences that speak to women but I also feel like you can truly love her work and be a man. What you say about Thompson and his masculine aesthetic and appeal as a counterpart is interesting. I think what made me bristle the most about Flanagan’s statements were that they seemed very borne out of self-interest rather than speaking to women as a whole. I still find that Flanagan’s commentary doesn’t recognize the depth and complexity of Didion’s work which is very grounded in the female experience but is certainly more than fashion, etc., (not that such writing couldn’t be deep and complex) as Flanagan discusses.

One day a couple years back I was a working a gig at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, and it happened to be what I believe was the first showing of her play about the death of her husband. Vanessa Redgrave was the first encounter of note of the day, her playing the Didion soliloquist, and she would smoke off the side of the building with an assistant standing by, while we hustled gear in and out. Later on she would ask for me for a cigarette and I would light it for her. As for Ms. Didion, she manifested herself during the sound check, which involved Ms. Redgrave standing onstage beneath the dome, mic’d up and walking around. They ran through the first time minutes ad infinitum, and but eventually did move on to what seemed like the whole first half of the play; Ms Redgrave was, of course, most professional. About halfway through this process I saw a very little, very dour woman sitting at the very back of the rows of chairs we’d put out, with her bag in her lap and her hands on her bag, sunglasses that swallowed half her face, and a jacket wrapped over her arms and around her body. The sound was being perfectly mixed to allow the echoes in that great, grey room, to fulfill the words, and it made everything seem bigger than it actually was, except her.

Perhaps she’d been called there to run over logistics, but I don’t think anyone knew who she was, and no one was talking to her. So she just sat there and listened to the opening of the play she wrote about her husband dying over, and over, and over. Eventually, when she was leaving, she encountered the thick velvet rope, linked with sturdy brass posts, we’d put up to keep the church’s visitors from transgressing on our work. She stood there a moment, having already had a great deal of trouble with this before, and I was standing very near her, and I reached out, and I lifted it up, and she smiled, and left.

Never did see the rest of the play.

As for this business, I think it gets in the way of meaningful progress to associate feminine and female aspects of qualities with the impossibility of masculine or male comprehension and response. Why can’t you just talk about what you understand, to the best of your abilities, the sensibility at work to be; and assume someone is going to respond.

Otherwise we just wind up having puffed up, irritated quibbles about how many women we know who do or do not like Hunter Thompson. And I know five men who adore Joan Didion! Only one of them’s gay, but he’s quite the bear!

And I think that’s where Flanagan misses the point the most–she refuses to see that part of what makes Joan Didion a specifically female icon is that she writes with such depth and complexity that she legitimizes “women’s writing.” It’s like she wants to sort of, I don’t know…hoard her? Hoard Didion’s talent as being ONLY specific to females instead of seeing that the lady-specific aspects are borne of her greater talent, and that they’re sort of a layer on top of what makes Didion a fantastic read for anyone regardless of sex. Which I understand; when I started reading her I wanted to feel like I alone had discovered some gem who spoke to me and me alone, but that’s a selfish, short-sighted reading. Am I calling Caitlin Flanagan short-sighted? Perhaps.

(And I absolutely did look around for dangling hair-dryers above my bathtub, etc., re: agreeing with Flanagan. O the day!)