Roundup

Emily +/- Dickinson

Last night for school I was asked to give a brief presentation on the importance of Emily Dickinson’s dashes. (I posted about this a few days ago.) My one sentence conclusion: “They’re nearly as important as the words are.” yeah ok whatever…

I did some further reading, though, and noticed/learned something I think is interesting: even among the “accepted,” contemporary, “dash-inclusive” collections of her work, the dashes still aren’t fully represented the way she wrote them in her manuscripts… and I’m not just talking about the hypen vs. en dash vs. em dash thing, but even their placement and existence.

Let’s get into some shit…

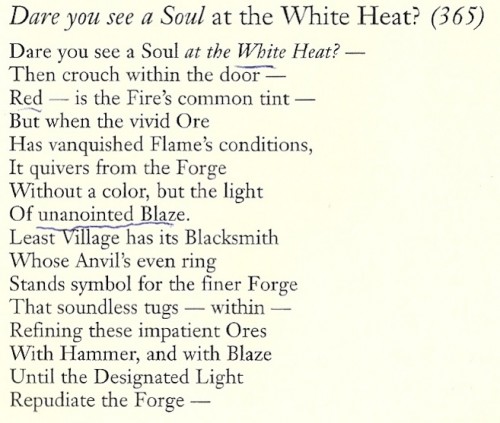

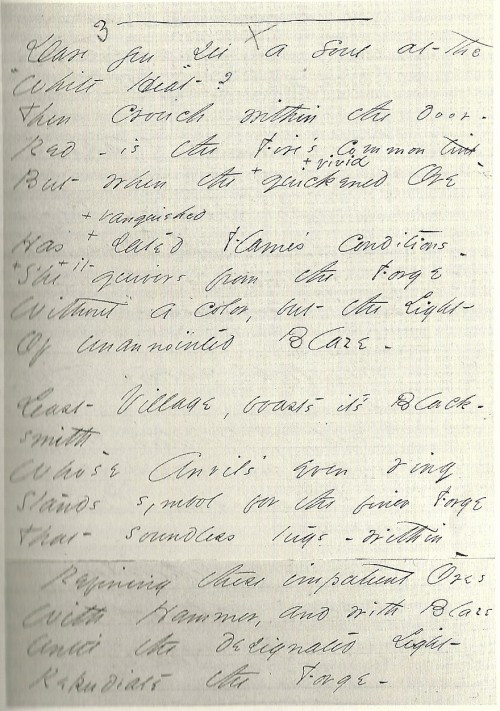

Here are two different versions of poem #365: 1) a copy of the original manuscript and 2) an all-inclusive print representation of the manuscript (both from Inflections of the Pen: Dash and Voice in Emily Dickinson by Paul Crumbley)

This is kind of interesting right? Her final manuscripts include alternate word choices, sometimes more-than-marginally effecting the outcome of the poem (e.g. “she” vs. “it”). Further, her manuscripts (most of them) were found bound in 40 separate booklets (“fasicles”), therefore possibly implying they were finished works — meant to be read with alternate words and all.

But she died. And her sister found the poems and got them published and the dashes were famously removed by editors.

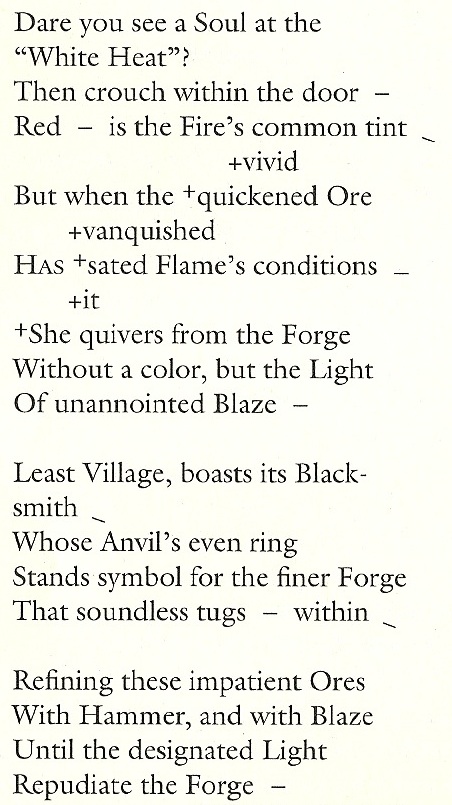

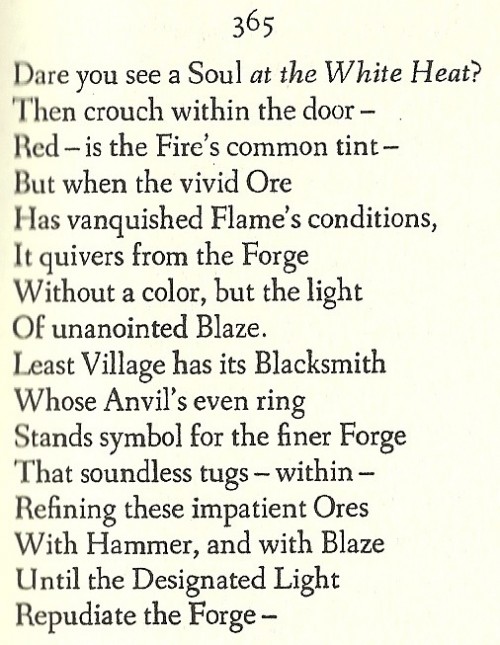

Here is poem #365 as it was published in 1924 (I think this was the earliest publication of it):

(SOURCE)

No dashes. Went with “vivid” over “quickened,” “sated” over “vanquished,” “it” over “she,” removed some quotation marks and capitalizations, even changed some words.

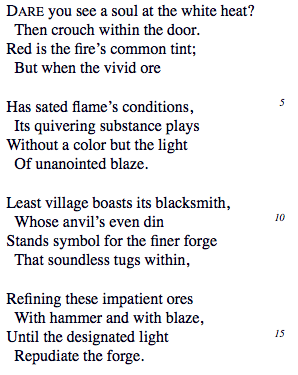

Now here’s the poem as it appears in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson edited by Thomas H. Johnson and originally published in 1960 (sorry for the blur on the left):

No stanza breaks. Quotations turned into italics. Went with “vivid,” “vanquished,” and “it.” The dash after “conditions” becomes a comma, the one after “blaze” becomes a period, the one after “blacksmith” is removed completely. (If you look at the manuscript, these marks are a little ambiguous, but I don’t see how you can call the line after “tint” a dash and not the lines after “conditions,” “Blaze,” or “blacksmith.”)

Here’s another contemporary version, this one from The Oxford Book of American Poetry edited by David Lehman (the retarded underlines are mine):

This is identical to the Johnson version with the exception of an added dash at the end of the first line. This dash is not present in the print reproduction of the manuscript (the 2nd image), but if you look closely at the original manuscript image there is what might be a dash after the word “Heat” but before the question mark, although this could also be the missed place cross of the “t” — it’s hard to tell. Either way, this dash in the Oxford version is a little weird.

This is identical to the Johnson version with the exception of an added dash at the end of the first line. This dash is not present in the print reproduction of the manuscript (the 2nd image), but if you look closely at the original manuscript image there is what might be a dash after the word “Heat” but before the question mark, although this could also be the missed place cross of the “t” — it’s hard to tell. Either way, this dash in the Oxford version is a little weird.

SO WHAT?

So, if you buy into the power/theory of Dickinson’s dashes — that they break up conventional thought processes and provoke the reader to a more active reading (these are conclusions we came to in class) — then the above discrepancies are not totally inconsequential. They make for different experiences and therefore different poems. For example, that dash at the end of the first line of the Oxford version could potentially be discussed ad nauseam (what does it mean???) even though it’s totally absent in other versions and might be a typo. Does it change the poem entirely? Not really. Is it a matter of life and death? No. I just think it’s funny that for all the “Dickinson without dashes is blasphemy!!” sentiment, there are still discrepancies between contemporary versions, and not all the dashes made the cut.

*Note: I am far from a Dickinson scholar. If I am wrong about any of this, please call me out.

Tags: editors, emily dickinson

fuck yeah!!!!!!!!!!

Well, in that overrun first line, the dash between the *Heat”* and the *?* is how Dickinson crossed her final “t”s. (I don’t see any mark on that line after the question mark at all. Oxford did a boo-boo.) There’s a similar, what, laterally dislocated cross, crossing the “t” in “at”, in that first line between *at* and *the*, and another in the first word of the fifth line: *But*. It’s a pattern, so an editor would be within reason to call all dashes after final, uncrossed “t”s the crosses for those letters and not any kind of dash – open, of course, to particularized objections.

In the case of *Blacksmith* or *Black-smith* – that is, ‘is “blacksmith” a hyphenated word for Dickinson?’ – , one would want to find other instances of the word in her hand; that failing, examples of similar words — some evidence to give reason, beyond caprice, to one’s editorial decision (of whether, in #365, to hyphenate the word as it’s printed all on one line).

And there’d be some ambiguity; if that’s her only “blacksmith”, and she has no other ‘smiths’, the editor would have to make a call with some foundation.

And so on. I don’t think her manuscripts are impossible reasonably to edit – that is, each decision can reflect a rational, useful defense, even to the satisfaction of a determinedly different perspective in some particular case (like ‘blacksmith’).

–

Dickinson is an example of a poet who needs to be read in variorum for close interest. Many of her poems have substitutions written right onto the one fair copy – which version was her last word? – answ.: put all the choices on the printed page and call that array the ‘poem’.

–

Andrew, “nearly as important as the words”? I hope you didn’t get a second helping of porridge. How about: ‘about as important as the capitalized first letters: something one sees and might hear, but nothing as solid and effectual as the words’.

interesting. nice job, man

Who is deadgod?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hFbCS4a14J4

– …. .. … -.-. — -. …- . .-. … .- – .. — -. .. … … — .-. . .-.. -.– .-.. .- -.-. -.- .. -. –. … — — . — — .-. … . -.-. — -.. . .-.-.- … — …. . .-. . .. – .. … .-.-.- -.– . .- …. .-.-.-

After reading your first post, I went back and started to do a little research on the dash — and, in particular the em dash, as we can assume Dickinson’s dashes were generally not hyphens or en dashes, which act to joint rather than separate. The em dash is typographical, invented in the 19th century, the hot metal days. I assume a double hyphen “–” served the purpose until then in printing? So in other words, while there was no em dash, there was the idea of the em dash and how it functioned grammatically. Still, did it work in Dickinson’s time the way it does now? Certainly Dickinson is working with another animal here in what you present: she’s not using the dashes like parentheses or ellipses or colons, or to interrupt speech or train of thought (or at least there are plenty of exceptions to the rules). But, paradoxically, we probably read these as em dashes — we’re grammatically wired to read them as such. However, because we’re up against that whole other animal we’ve never seen before, we may be misreading.

ha ha ha

In that clip, I fantasize (project?) that Larry desperately wants to say ‘me, too; me, too’, but that being both Pope and King stops him.

(Maybe it’s that ‘included only as boss’ bitterness that stops (some) people from being mathematically rational and ethically just in their politics, and turns them into fiscal ‘conservatives’ instead.)

It’s too bad Douglas couldn’t do for Kubrick what Heston did for Welles with Touch of Evil, but I guess fleeing Hollywoodland saved Kubrick.

Why make that ‘assumption’, beardobees?

All punctuation both joins and separates, doesn’t it? It’s a matter of the work of each articulation . . .

Em dashes – the wide marks that (virtually) touch the last and first letters of the words on either side, respectively – don’t look, to me, like what Dicko actually jotted, which materiality I take to be a strong principle in ‘translating’ her writing into typography.

For example, look at the first two words in the third (complete) line of the fair copy of #365 (above): “Red – is”. The mark between the “d” and the “i” – and quite separate from either – is narrower than any of the letters in “Red” and, slanted as they are, about as wide as each of the letters in “is”.

How is that mark not a spaced en dash??

Christ, man – lives are at stake.

I think I have a headache now… but I am glad you prompted this discussion. I always assumed the dash she (over)used was a replacement for any or all punctuation whenever she felt like it. This runs into the arena of private poems versus public work. Since these were private thoughts, isolated moments of a extreme personality I venture to say she wrote without a strict guideline. As mentioned above by deadgod, E.D. left behind variations of many verses…

Where did you find the image of the MS by the way? It could be useful for my lectures.

fuck yeah

That’s interesting. I think I remember reading that “dashes” (not sure if specifics were specified) were fairly common in personal correspondence in her time and apparently her letters are full of them. I think it was on those grounds that editors were like “yeah whatever fuck these things, they shouldn’t be in poems.”

That said, Dickinson’s use of the dash — whether it be em, en, or hyphen — doesn’t seem to conform to any standard grammatical rules, which I guess is what makes them fun but also so hard to edit.

Like regardless of the em dash’s conception in her time, would she have cared or adhere to it?

That’s interesting. I think I remember reading that “dashes” (not sure if specifics were specified) were fairly common in personal correspondence in her time and apparently her letters are full of them. I think it was on those grounds that editors were like “yeah whatever fuck these things, they shouldn’t be in poems.”

That said, Dickinson’s use of the dash — whether it be em, en, or hyphen — doesn’t seem to conform to any standard grammatical rules, which I guess is what makes them fun but also so hard to edit.

Like regardless of the em dash’s conception in her time, would she have cared or adhere to it?

“Inflections of the Pen: Dash and Voice in Emily Dickinson” by Paul Crumbley

[…] * Historische tekstanalyse van een gedicht van Emily Dickinson. […]

Great discussion. Only thing I’d add is that the Johnson version stems from a different manuscript of the poem (there are two extant), which doesn’t have the stanza breaks or quotation marks. So some of what he does has manuscript authority.

Great discussion. Only thing I’d add is that the Johnson version stems from a different manuscript of the poem (there are two extant), which doesn’t have the stanza breaks or quotation marks. So some of what he does has manuscript authority.

Exactly. There’s a nice summary of Johnson’s (and Ralph W. Franklin’s later) editing of the poem at the start of this:

http://eraofcasualfridays.net/2009/12/11/dare-you-see-a-soul-at-the-white-heat/

[…] You know those books that have places where you can choose alternative plot paths and/or alternative endings. Miss Emily did something like that. […]