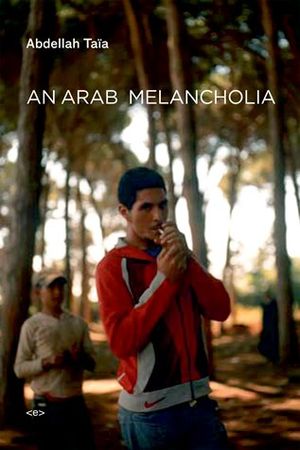

An Arab Melancholia

An Arab Melancholia

An Arab Melancholia

by Abdellah Taïa

Semiotext(e), March 2012

141 Pages / $14.95 Buy from MIT Press or Amazon

In consideration of the memoir, or autobiographical non-fiction, It could be said that I take issue with the genre. Generally. As a mode of writing, the market tends to be overrun by a multitude of examples of the dominant narrative—that of the straight white man—and when the Other breaks into the limelight of that best-sellers table at your local Barnes & Noble, it’s generally within the context of a very approachable, almost white-washed context. Books for the middle-class to buy and read and convince themselves that they know about the world. I realize this might sound unduly harsh, but my experience has lead to the building of this experience, whether it’s fair to the publishing world as a whole or not.

I think that Semiotext(e) demonstrates an awareness of the shortcomings associated with the overarching title of “memoir”—instead of using the term in any of their press materials for Taïa’s book, the term “autobiographical novel” is used. This is an important semantic justification, in that it removes the book from the context of the zeitgeist that it would immediately find itself outside of.

But perhaps form follows function, as Taïa himself is a gay Morrocan writing explicitly about his experiences. Not only is he doing this, he also seems to be the first “openly gay autobiographical writer published in Morroco.” This is honest writing from a marginalized position.

In her article, “Experimentalism, Why?,” Camille Roy offers the suggestion that ‘experimental’ writing, being inherently marginalized, is a perfect mode of writing for the marginalized writer to explore. Taïa’s prose is ostensibly straight-forward—he eschews linearity, sure, piecing his narrative together by presenting fragments of the past out of order—but the language itself displays characters (people) in conflict, events, dialog, psychological insight. And there is, in this case, nothing problematic about that.

The novel begins by invoking Taïa’s childhood, and importantly, offers an incident which immediately removes Taïa, as the first-person narrator, from the conext of the ‘victim,’ particularly vis-a-vis his homosexuality. Considering that the rest of the book addresses, ostensibly, a break-up that marks Taïa far more than he’d like, this is a wise textual move. It refuses the reader the opportunity to develop a sentimental empathy; we cannot pity Taïa because we know he is strong—his sadness is a considered sadness, a larger issue than simply the immediate frustration encountered when facing the reality that YOU love someone who does not love YOU back. This is a symptomatic melancholia, the vague opportunism of the world when it encounters someone (our narrator, Taïa), who stays stubbornly romantic.

The tableau offered to launch the book offers an almost ecstastic holiness, a self-considered realization, a contra-monde mode of being decided early-on in youth—an ecstasy interrupted only by death. A death of the self, both literally and metaphorically.

Death haunts the book, or perhaps just that unknown that we call death when no other language seems adequate. An accidental electrocution, a wavering plane, the crushed spirit. Taïa pulls through all of these paroxysms with a renewed will, a hope, a decisive intent. Perhaps this is not the best narrative to inject into middle-America’s current “It Gets Better” campaign/obsession (problematic in its own right). But this reality is what the book leaves with its readers; an insistence that through everything there is always something else that follows. It’s neither a hesitant optimism nor a beaten-down acceptance, a nihilism; it’s something else, something more human. The weight of the world cannot be taken on as the Sisyphean boulder, but rather we have to just forget about the world and make sure we’re moving forward.

March 29th, 2012 / 6:59 pm