The Day Irony Stood Still: On Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge

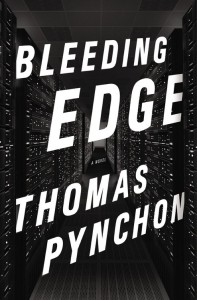

Bleeding Edge

Bleeding Edge

by Thomas Pynchon

Penguin Press HC, Sept 2013

496 pages / $28.95 Buy from Amazon or Indiebound

“I met a lot of hard-boiled eggs in my life, but you — you’re twenty minutes.” — Lorraine Minosa, Ace in the Hole (1951)

The appeal of the hard-boiled character archetype is their indefatigable coolness, their aloofness. We seem to like characters who react in seemingly inhuman ways to moments and situations in which the rest of us would be too consumed by nerves or emotions to construct a sentence, let alone a biting bit of wordplay. These characters are mostly at home in the dimly lit offices and back alleyways of the film noir detective, but we see permutations of the archetype every time we encounter a dominant lead with a penchant for mouthing off to baddies with guns.

Hard-boiled works best with snoops, and Thomas Pynchon has veered his career into continuing to explore the limits of this character type, setting up camp everywhere from the Revolutionary War (Mason & Dixon) to 1980’s California (Vineland) with a cast of irreverent characters who never cease to check the self-importance of not only their verbal sparring partners, but of moments themselves.

But what Pynchon has chosen to explore in Bleeding Edge, his seventh novel, is what would happen if you took all of those Pychonian elements of irony and placed them in a time and place in which it didn’t stand out, and was, in fact, par for the course.

Maxine Tarnow, a rogue (or at least de-licensed) fraud investigator and single-ish (it’s complicated) mother of two, plays the part of our protagonist. She is, as teh novel opens, approached by Reg Despard, a filmmaker acquaintance, to look into the finances of a shady enterprise called hashlingrz, a deep-pocketed Internet company buying up infrastructure and failed start-ups that went under after the .Com bubble burst, a fate which hashlingrz itself somehow sidestepped. From there, we begin to fall headlong into lengthy list of classic noir tropes: the numbers that don’t add up, the seedy-yet-likable characters of the city’s underbelly, the overseas connections, and yes, even an homme fatale. New York City looms large (doesn’t it always?) as the book’s backdrop, not simply because of Pynchon’s love for it — Bleeding Edge is an unashamed love letter to the city — but because of what we all know to be coming: the book begins in March of 2001, and will lead us by the hand through nearly a year, including, of course, 11 September. If there’s reason to question Pynchon’s decided lack of in-depth development for any of the book’s other characters, it’s because New York itself is our secondary — or perhaps even primary — protagonist, itself “twenty minutes” in hot water.

Maxine, in all her hard-boiled glory, is Pynchon’s representation of irony incarnate, not that other sources aren’t otherwise readily available. But it’s through her that the book drives home it’s final point re:the death or non-death of irony, which is that 11 September did not kill irony, a claim that has manifested itself countless times in the last twelve odd years. What it did was remind us that irony doesn’t work all of the time, and for it to retain its bite, you have to allow for moments of fear and sincerity and bravery, not to mention silence. “For many people, especially in New York,” Pynchon jabs, “laughing is a way of being loud without having to say anything.”

When discussing postmodernism in general, and Pynchon in particular, these days, irony is the word burning on every tongue of every critic/commentator, easily the most vilified and misused word of the past decade and a half.

It’s nearly impossible to discuss postmodern irony without making reference to “E Pluribus Unum: Television and U.S. Fiction”, the ubiquitous essay by the late David Foster Wallace that decried mass culture’s co-option and subsequent neutering of irony, and proposed a revival of sincerity.

“The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels,” Wallace wrote, “born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue.

While a new group of authors, Wallace, Franzen, Safran Foer et. all, ushered in a new era of sincerity in high art, the true cultural rot that Wallace had warned against wasn’t happening in lit mags, but quietly on the lower rungs of the cultural ladder. Most people took DFW’s essay as a grand metaphor for literature, but anyone with any cursory biographical knowledge of Wallace would know that he loved, to the point of addiction, bad television. And it was here that Wallace saw the writing on the wall. The Mark Leyners of the world were never the problem. Literature was too diffuse even then to really have the sort of devastating societal ramifications that Wallace foretold; but if you lose sincerity in “low” art, when it embraces what it is and no longer holds any pretensions about maybe passing as the “real” thing, and when it multiplies like wildfire, you’re doomed.

““Ain’t like I was ever Alfred Hitchcock or somethin,” Maxine’s filmmaker friend/client-pro-bono Reg admits proudly. “You can watch my stuff till you’re cross-eyed and there’ll never be any deeper meaning. I see something interesting, I shoot it is all. Future of film if you want to know—someday, more bandwidth, more video files up on the Internet, everybody’ll be shootin everything, way too much to look at, nothin will mean shit. Think of me as the prophet of that.”

December 2nd, 2013 / 12:00 pm