Genius

Genius

Genius

Written by Steven T. Seagle, Illustrated by Teddy Kristiansen

First Second, July 2013

128 pages / $17.99 Buy from First Second or Amazon

“Physics isn’t the most important thing. Love is.”

― Richard Feynman

Ted isn’t a genius. If he ever was a genius, it was when he was a child, skipping two grades, and postulating what the universe is expanding into (“red”). Now, he rides a desk in a cube farm, and his boss (the legendary “Needham”) is tiring of waiting for Ted’s to produce. Ted is an everyman physicist of an unspecified type. Whatever his area of work, it is definitely theoretical; he hasn’t published in years, though not for lack of trying.

It’s not an explicit threat, but Ted is still desperate—not just to save his job and livelihood, but to come up with that “one big idea” that will revolutionize the field, recapture his youthful genius, and allay his self-doubt all in one.

It’s no wonder that he’s having trouble producing anything.

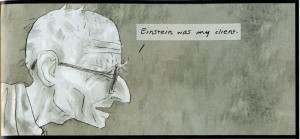

This is not a young man’s game, Genius reminds us, in following with conventional wisdom from A Mathematician’s Apology on down through A Beautiful Mind. It’s certainly not a family man’s game, and most of the times we see Ted sitting down to think, he is interrupted to attend to family matters. At home his teenage son Aron is discovering the joys and horrors of puberty. His wife Hope is waiting for her test results from the doctor. His father-in-law (Frances) is his main foil, delivering barbs that are just as devastating whether he remembers who his son-in-law is or not. But Ted’s last longshot chance is a secret that Frances knows: a secret that Einstein himself told Frances when he was his bodyguard.

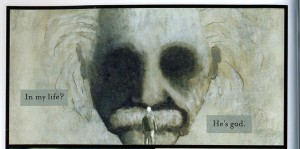

In Ted’s self-doubt he thinks often of Albert Einstein. The man is his god; he proclaims it straight out. Einstein appears in Ted’s dreams and daydreams—not as the man himself or even a character, but as an avatar of what Ted longs to attain but cannot.

Genius makes an idol of Albert Einstein, but this story’s true spiritual deity is Richard Feynman. Einstein is about the whimsy of physics; Oppenheimer is about the tragedy. Feynman on the other hand, is all about the love.

Genius makes an idol of Albert Einstein, but this story’s true spiritual deity is Richard Feynman. Einstein is about the whimsy of physics; Oppenheimer is about the tragedy. Feynman on the other hand, is all about the love.

The difficulty in writing a good scientific genius story is in interpreting high level, high concept theory into an emotional narrative without betraying the source material. There are brilliant works of fiction about, for example, theoretical mathematicians. Arcadia is one, and Proof. Gödel, Escher, Bach is another recent example, a popular nonfiction text that doesn’t pull its punches when it comes to high level science.

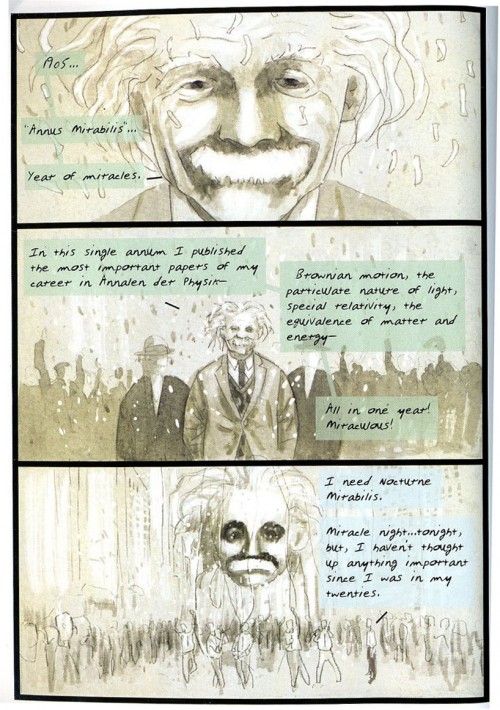

For all of Genius’s professed love, there is surprisingly little “capital s” Science. The “science” presented here is more a set of symbols and idols. Like the Bohr model atoms pervade the art—a simplified representation of a much more interesting, complex system. Perhaps this is the reason Seagle and Kristiansen focus exclusively on Einstein: the man so synonymous with genius that his name has become a cliché. Everyone can appreciate the meaning of an “Einstein,” even if they have no concept of Newtonian physics, let alone special relativity.

For all of Genius’s professed love, there is surprisingly little “capital s” Science. The “science” presented here is more a set of symbols and idols. Like the Bohr model atoms pervade the art—a simplified representation of a much more interesting, complex system. Perhaps this is the reason Seagle and Kristiansen focus exclusively on Einstein: the man so synonymous with genius that his name has become a cliché. Everyone can appreciate the meaning of an “Einstein,” even if they have no concept of Newtonian physics, let alone special relativity.

There is a familiar, legitimate emotion to this mindset. Imagine a precocious child in his classroom, bored of the lesson, daydreaming of his idols—Einstein, Edison, Nobel. The scientists in his textbooks are sidebar deities, a portrait and a list of their great achievements. A child has no references for the real-world research process. He doesn’t know anything of the long, hard slog of scientific experimentation or the complex intellectual work of theory. He imagines a secret, held in the minds of the scientists who thought it up.

When Ted has his big realization (as he must) it is represented by grunge watercolor spreads. The spreads do a decent job of graphically representing the feeling of having hit upon a brilliant idea, only to have it slowly fade away as you try to capture it. Often the art has bits of text and scrawled equations to allude to underlying scientific principles.

November 25th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Girlchild by Tupelo Hassman

Girlchild

Girlchild

by Tupelo Hassman

Picador, Feb 2013

288 pages / $15 Buy from Amazon

Rory Dawn, the screaming sunrise, is third generation in a line of women who grew up too soon, and grew up to grinding poverty. She lives with her mother in a trailer park outside of Reno called the Calle. The Calle is a dumping ground for all the usual white trash suspects: drinking and gambling and smoking and teen pregnancy. There is also plenty of literal garbage (popsicle sticks, beer cans, homework assignments) swirling around in the Nevada dust. The kind of place where people regularly have to choose between paying the water bill to keep the toilet running, or buying a tank of propane to keep the heat going.

Rory’s mother, Jo, tends bar when she’s not sidled up to one. She lost her teeth young, and Rory’s greatest joy in life is seeing her smile wide, without her hand hiding her dentures. Rory’s grandmother lives in the trailer down the way, and spends her time gambling, knitting, and trying to make things grow in the harsh dirt. Both women want nothing more than for Rory Dawn than to grow up and “get out,” without making the mistakes they did. Neither has the first idea how to help her achieve this goal.

Growing up is a dangerous journey for Rory. At school, she performs off the charts on standardized tests, and scrawls “I hate Rory Dawn” on the bathroom wall. On the Calle, predators like the Hardware Man won’t even wait until a girl like Rory starts to fill out.

Girlchild works hard to rid us of any notion that the point of the story is whether or not Rory will “get out.” Calle life is a circle, and it’s impossible to draw the line where the past meets the future. They call poverty a vicious cycle, after all. To this end, Girlchild is told in a disjointed, highly metaphorical narrative, jumping around among all the most mundane and most heartbreaking moments of Rory’s childhood. Much of the story is in 1-3 page mixed genre vignettes, many of them sad and clever, like the word problems that make no sense and have no real answers.

August 5th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Almost Gone by Brian Sousa

Almost Gone

Almost Gone

by Brian Sousa

Tagus Press at UMass Dartmouth, February 2013

192 pages / $19.95 Buy from Tagus Press or Amazon

Brian Sousa’s debut is a novel-in-stories about the life and tragedies of three generations of a Portuguese-American family living in Rhode Island. Their lives are punctuated with a series of desperate escapes abroad, beginning with Scott on the beaches of Brazil mourning the death of his young daughter, re-enacting her drowning in several senses of the word. He doesn’t know that it was a similar flight of desperation that brought his grandmother and grandfather to America from Lagos, Portugal many years ago.

The characters may occasionally run, but they cannot hide from their literary fate. Each character’s private pain explored in turn; each timely revelation increases the stakes. Helena emigrates from Lagos with her husband Nuno, and finds her life in America barren and cruel in comparison. Nuno cannot muster any grief for his wife’s death, and instead nurses his obsession with Catarina, the beautiful Portuguese woman who lives in the guest cottage behind his house. Nuno’s son Paulo listens to his teenage son Scott having sex, while his own marriage is rapidly deteriorating around him. Ten years later, Scott’s marriage is no better: he loses his child and abandons his wife. The unwitting observer to all of this family drama is Catarina, who can never seem to escape her fate as the object of every man’s desire. She too leaves her husband, fleeing into the streets of Granada.

These are stories of loss, infidelity, alienation…all the persistent demons of modern suburban life. And for that matter, of suburban literature since the dawn of Cheever. But Almost Gone glimmers when Sousa manages to step outside conventional grief, and twist the knife ever so slightly. The best example of this is a deeply awkward scene where Nuno arrives at the cottage to woo Catarina, after his son Paulo has just tried the same and left, rejected. Nuno falls, and pleads with her from the ground:

May 17th, 2013 / 11:00 am