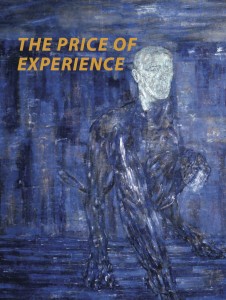

Price of Experience by Clayton Eshleman

Price of Experience

Price of Experience

by Clayton Eshleman

Black Widow Press, 2012

483 pages / $24 Buy from Amazon or Black Widow Press

The Price of Experience is a broad sampling of Eshleman’s prodigious output in a variety of literary forms: poems, letters, interviews, book reviews, essays on contemporary art, and lectures on ice age cave art, are all brought into the mix alongside various memoir bits and notes on his numerous translation as well as editorial projects. (Eshleman indispensably translates the poetry of both César Vallejo and Aimé Césaire, among others. He also edited the seminal journals Caterpillar and Sulfur.) This would be considered an “Eshleman Reader” if only somewhat incredibly it didn’t follow on the heels of Black Widow Press’ previously published The Grindstone of Rapport: A Clayton Eshleman Reader (forty years of poetry, prose, and translations). Meanwhile, it also looks forward to their publication of Penetralia (a fifty-seven-year poetry retrospective) in 2015. It’s daunting (and perversely thrilling) to imagine what the page count for the upcoming “retrospective” might turn out to be as the other two books come in at around 500 pages each.

Eshleman grabs his book’s title from lines of William Blake’s The Four Zoas and the lesson expounded by the work of the poet-mystic-printer is ever apt. Eshleman quotes an extensive passage, but here are the opening lines:

Or wisdom for a dance in the street? No it is bought with the price

Of all that a man hath his house his wife his children

Wisdom is sold in the desolate market where none come to buy

And in the witherd field where the farmer plows for bread in vain

In essence, given this epigraph, which ends “It is an easy thing to rejoice in the tents of prosperity / Thus could I sing & thus rejoice, but it is not so with me!” Eshleman seeks to frame this retrospective accounting of his work in a fashion which demonstrates how thoroughly his writing arises quite literally from struggles surrounding the circumstances in which he’s lived. There should be no doubting that Eshleman has done his fair share of downward scraping into the barrel of experience, bottomless as it may be. He has always returned to his work positioning his imagination via writing in the hands of forces over which he often feels no control. The resulting discoveries astound him as much as anybody else. In fact, they sometimes astound him quite a bit more than they likely do anybody else.

The limits of Eshleman’s writing arise when his impulse for self-expression overrides and self-indulgence swells within him, his proclivity for excess then gets the better of him. One case in point: while detailing his relationship with poet Paul Blackburn, Eshleman describes how his own personal demands tore him away from composing a poem for Blackburn’s second wedding and instead turned him towards writing a massive poem—as yet unpublished in its entirety—full of his working through deeply personal psychological material from out his own past.

August 2nd, 2013 / 11:00 am