A Tiny Addendum to Paul Auster’s Concept Concerning “Boy Writers”

On 16 January 2014, a writer boy named Paul Auster conversed with someone named Dr. Isaac Gewirtz (this boy likely had friends & relations who were a part of the Holocaust) at the Morgan Library (which seems quite splendid, though it may not be if Mayor Bloomberg was able to blow his matzoh-ball-soup breath on it).

According to girl writer & Huffington Post blogger Anne Margaret Daniel, Paul put forth the category of a “boy writer,” which means:

someone who is so excited, takes such a sense of glee and delight in being clever, in puzzles, in games, in… and you can feel these boys cackling in their rooms when they write a good sentence, just enjoying the whole adventure of it. And the boy writers are the ones you read, and you understand why you love literature so much.

I concur with Paul — because of “boy writers,” literature is the best thing ever (except Christianity).

Arthur Rimbaud is a boy writer, which is why he stabbed people at poetry readings and yelled “shit” after the insipid readers declaimed their dull verse.

Edgar Allan Poe, as Paul points out, is a boy writer, as he composed stories on murder and poems on special girls, like the “beautiful Annabel Lee.”

There’s not a lot of boy writers who are un-dead. Most, nowadays, correspond to what Paul terms a “grown-up writer.” Stephen Burt, Carl Phillips, Dobby Gibson, Geoffrey G. O’Brien, Bob Hicok are examples of a “grown-up writer.” They don’t spotlight the “puzzles” and the “games” of the violence, theatricality, exploitation, and upsetness in the postlapsarian world. They document liberal middle class averageness. “It’s about settling down and settling in,” says Burt.

But some boy writers are un-dead.

Johannes Goransson likes makeup and violence. “mascara is infected / belongs to assaults,” the Action Books editor and boy writer elucidates in Pilot (Johann the Carousel Horse).

HTML Giant’s own Blake Butler is a boy writer. In Sky Saw, his characters aren’t given names but numbers (just like in the Holocaust and in the War on Terror). Reading his books are sort of close to witnessing a disembowelment.

Paul Legault (because he likes Emily Dickinson like someone would like an American Girl doll), Walter Mackey (because he likes Barbie), and Julian Brolaski (because his language reads like sticky, sweet, chewy watermelon bubblegum), are all un-dead boy writers.

But the best boy writers (maybe ever) are dead, and they’re Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. Glee? Delight? Cackling in their rooms? Enjoying the whole adventure? All the attribute’s of Paul’s boy writer align with Eric and Dylan. They kept journals, websites, and videos so everyone in the whole wide world could be cognizant of the glee-enjoying-cackling-delight-adventure that they had in planning their massacre. As Eric stated, “I could convince them that I’m going to climb Mount Everest, or that I have a twin brother growing out of my back. I can make you believe anything.”

Boys Who Kill: Kevin Khatchadourian

The final Boys Who Kill for the time being brings the spotlight to Kevin Khatchadourian. On 10 April 1999, ten days prior to Dylan and Eric’s premiere of NBK, Kevin killed his daddy and his sister before going to school and murdering seven students, one English teacher, and one janitor in the gym.

Growing up, Kevin’s two favorite words, according to his mommy, were “Idonlikedat” and “dumb.” Whether it was his mommy’s milk, his mommy’s cooking, his mommy in general, music, or cartoons, Kevin’s would probably be displeased by it. Although, there are some things that Kevin does like, like computer viruses and Robin Hood. Both Robin Hood and computer viruses attack targets that possess plenty of materials. Robin Hood deprives rich people of their things and computer viruses deprive computers of their ability to preserve their multitude of files and functions.

Kevin’s granddaddy and grandmommy maintain a motto: “Materials are everything.” The granddaddy and grandmommy fill their lives by doing things. They install water softeners and purchase first-rate 1000-dollar speakers, even though they don’t really like music all that much. As for Kevin, his mommy says that he “was never one to deceive himself that, by merely filling it, he was putting his time to productive use.” While 99 percent of people spend their Saturday afternoons doing something, like speculating on what they intend to do that night or checking their social media feeds, Kevin is “doing nothing but reviling every second of every minute of his.” With a tough tummy, Kevin can do what the phony baloneys can’t: “face the void.”

Simone Weil has a similar perspective on life. For the French ascetic, nothingness is truthfulness since it has to do with God. “We can only know one thing about God: that he is what we are not,” says Simone in her notebooks. God isn’t composed of matter nor is he quantifiable. Unlike humans, there is no corporeal limit to God. He is infinite. Humans are a sham. They use their days trying to satiate various desires (hunger, thirst, xxx, and so on) even though these hankerings can never be permanently filled because human beings are really just one giant hole. As Simone declares, “Human life is impossible.” Simone and Kevin each confront the hopelessness of fulfillment in a material and fleshy existence. They each effect divinity through destruction — Simone destroys herself and Kevin destroy the things and people around him. READ MORE >

Boys Who Kill: Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb

The third installment of Boys Who Kill stars Nathan Leopold (right) and Richard Loeb (left). On 21 May 1924 in Chicago, Nathan and Richard kidnapped and killed a 14-year-old boy.

Nathan and Richard each had daddies who amassed mountains of money. Nathan’s daddy owned one of the biggest shipping business in the country and Richard’s daddy was the vice president of Sears Roebuck. But the wealth that surrounded them didn’t dispel boredom. The two didn’t want money, they aimed for fame, sensationalism, and transgression. One of Richard’s favorite dreams had him as a notorious criminal who was beat and whipped in public, with girls and boys arriving in droves to express their mixture of awe, sympathy, and disgust. As for Nathan, he envisioned himself as a king’s favorite slave. One day, Nathan saved the king’s life, and the king offered to set him free, but, being loyal, Nathan declined. Both fantasies are rather Jean Genet: they are sumptuous, romantic, and somewhat sordid.

Like that French prison boy, Nathan and Richard carried out many crimes, including stealing automobiles and smashing bricks through windows. Mostly, though, the crimes were initiated by Richard, who insisted that Nathan come along to serve as an audience. After the two stole a typewriter and other possessions from Richard’s former frat house at the University of Michigan, Nathan became upset at Richard because the latter wasn’t wasn’t having enough xxx with the former.

Nathan and Richard’s friendship/boyfriendship sort of resembles the typical depiction (though it’s likely bullcrap) of Eric and Dylan. Eric is the aggressor and Dylan is the follower. Eric constructed NBK and Dylan just acquiesced. It’s also been rumored that Eric and Dylan liked boys (though that’s definitely bullcrap). Columbine jocks told the media that the two BFFs were a part of the Trench Coat Mafia, whose members touched one another in hallways and convened group showers. In Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, the two Columbine-esque boys get into the shower together and kiss and maybe do other things before they commit their high school massacre.

But Nathan and Richard really did like boys. Though Richard was perceived as the leader, he was the one who took it in the tushy. That this is so, sort of confounds how boys who take in the tushy are assessed. Richard engineered many crimes, including murder, so maybe boys who take in the tushy aren’t all basic bitches after all. Another hypothetical reason for why Richard took it in the tushy is, as he declared to friends, he didn’t need xxx. Richard was beyond lust and all of that other stuff that occupies the ironic minds of 20-something Brooklyners day and night. The symbolism about taking it in the tushy had no effect on him, as he only cared about a life of crime.

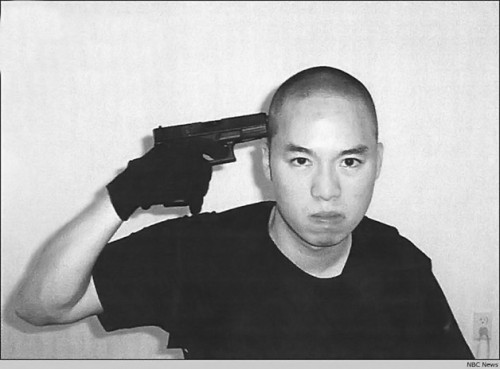

Boys Who Kill: Cho Seung-Hui

The next installment of Boys Who Kill stars Cho Seung-Hui, or Seung-Hui Cho, or Question Mark. On 16 April 2007, 4 days before the 7th anniversary of Columbine, Cho killed 32 people at Virginia Tech. First he visited West Ambler Johnston Hall, a dorm room for both boys and girls, where he killed one boy and one girl. Then he traveled to Norris Hall, a classroom building, and killed 30 more people.

Ever since Cho was taken out of his mommy’s tummy he hasn’t taken to talking. “Talk, she just him to walk,” says Cho’s great aunt about his mommy. “When I told his mother that he was a good boy, quiet but well behaved, she said she would rather have him respond to her when talked to than be good and meek.” At Virginia Tech, one of Cho’s roommates remarked, “I would see him walking to class and I would say ‘hey’ to him and he wouldn’t even look at me.” Other students concluded that he was a deaf-mute. He ate myself all by himself, and when someone offered him 10 dollars to say something, he said nothing. According to medical professionals, Cho suffered from “selective mutism.”

I, too, would prefer to be mute, and so, it seems, do other boys. Holden Caulfield dreams about being a deaf mute, and, it’s been reported by various biographers that instead of engaging in dinner table conversation, Arthur Rimbaud would just growl. Talking is terribly human — this race of creatures does in it grotesque quantities: they talk at Whole Foods, at overpriced bars, at trendy coffee shops, and, obviously, through Gmail, Gchat, texts, Facebook, Twitter, Disqus, and so on.

Cho’s contempt for normal communication distinguishes him from humans. Virginia Tech students and teachers constantly construct Cho as boy who confound expected human behavior. A professor labeled him “disturbing” and “unusual.” A student in his playwriting class said Cho “was just off, in a very creepy way.” According to Nikki Giovanni, students started skipping her poetry class due to Cho’s behavior . When Nikki told him to either cease composing sinister poems or drop her class, Cho replied, “You can’t make me.” Eventually the then head of the English Department, Lucinda Roy, tutored him privately. But even Lucinda was afraid of him. During the one-on-one tutoring appointments, Lucinda and her assistant agreed upon a code word that would prompt the assistant to summon security when uttered.

Based on this testimony, Cho is similar to a virus or a disease. No one wants to be around him; everyone is horrified of his presence. Not one to stay up into the wee hours of the morning to drink, party, and partake in sexual intercourse, Cho went to bed early and awoke early. He also played basketball alone. According to the New York Times, Cho was in a “suffocating cocoon.” (Being in a “suffocating cocoon” seems very dramatic and cosy; it also seems as if a “suffocating cocoon” would provide protection from mankind.) Virginia Tech journalism professor Roland Lazenby sums up Cho as a “shadow figure, locked in a world of willful silence.” Both Lazenby and the Times portray an incomprehensible boy who, isn’t free and liberated like Western subjects, but is held captive by a dark dangerous force. As Theresa Walsh, a girl who witnessed the killings in Norris Hall, says, “I’ve never really thought of him as a person. To me, he doesn’t have a name. He’s always been just the ‘the shooter’ or ‘the killer.'”