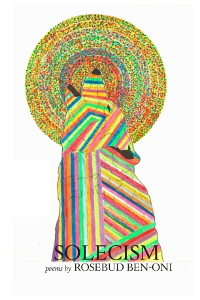

Solecism by Rosebud Ben-Oni

Solecism

Solecism

by Rosebud Ben-Oni

Virtual Artists Collective, 2013

80 pages / $15 Buy from Powell’s or Amazon

The phrase “identity poetics” has always struck me as strange. “Identity” comes from a Latin word that means most nearly “being the same,” and “poetics” from an Indo-Euro base for “one who collects, or assembles.” But “to be the same as one who assembles,” means every poet’s an identity poet, and from certain angles, dripping wax over thester scrolls in a dank hovel of some dentine tower, that’s probably true. But I’d wager most people interested enough in “identity” to consider it together with “poetics” consider the “id” (most literally just simply “it,” as in “id est”) in “identity,” and thus some other entity must assume that pesky pronoun. Hence, identity poetics qua the familiar orientations: sex, class, and the hyphenate ethnic camps (African-, Asian-, Latin-, et c.).

But when a poet’s got not just one, but two (or more), and wildly—let’s not say oppositional, but incommensurable—competing and/or complementary identities, the poetic stakes increase exponentially. So’s the case with Rosebud Ben-Oni (whose given name trumps any nom-de-plumes that arise to mind). Daughter of a Jewish father and a Mexican mother, Ben-Oni’s poems carry that heritage into the nonstandard impropriety of Solecism, a book of exodus and translation. These poems, rooted in autobiography, enact politics in ways that fail to strike one reluctant pedant as even remotely didactic.

Ben-Oni starts with the motherland and charts expanding circles with Israel, Mexico, and Manhattan at the respective center of each. The book’s scope expands to encompass the Middle East at large, all the borderlands’ length, and the greater metropolitan boroughs, winding up finally in Hong Kong (we’ll get there). Her course proves most interesting when these circles intersect, as with forgotten, historic Baghdad Beach of Matamoros, Mexico (which even seagulls, it seems, seek to flee) or Mt. Scopus, “an Israeli enclave in Arab East Jerusalem,” a territory likewise divided.

Ben-Oni’s poems don’t seek to bridge these divides or to reconcile a sympathetic speaker to this world defined by walls. Neither does she let the reader waffle in some non-space of dialectical nonsense. Instead, she collects words and phrases from across several languages and dialects to shape the collection’s texture, composed as much of Prospect Park and Flushing, Queens as it is tahini and achiote. Ben-Oni italicizes select words in Spanish (“colonia”), Hebrew (“dabar”), and Arabic (“wadi”), which she defines in footnotes, plus others in English, now chiefly North American (like “rawboned,” e.g.). The effect at first is like that old adage about Dick Branson tossing darts at a map: it may seem scattershot and haphazard, but the lexical globetrotting echoes always those sites I have to believe Ben-Oni’s speakers call home, strong as the drive for relocation may be.

July 26th, 2013 / 11:00 am