Fabled Lives: A review of Drops on the Water by Eric G. Müller and Matthew Zanoni Müller

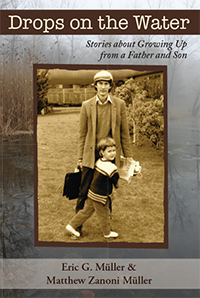

Drops on the Water

Drops on the Water

by Eric G. Müller and Matthew Zanoni Müller

Apprentice House, 2014

274 pages / $16.95 Buy from Apprentice House or Amazon

Vladimir Nabokov once said “…literature was born on the day a boy came crying wolf, wolf and there was no wolf behind him…Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story there is a shimmering go-between. That go-between, that prism, is the art of literature.”

In their debut memoir, Drops on the Water (Apprentice House 2014), co-authors Eric G. Müller and Matthew Zanoni Müller conjure those dark, shimmering tales of childhood.

A collection billed as “stories about growing up from a father and son,” the book’s structure appears deceptively simple: a chronological staging of moments from each of these writers’ young lives. This, however, is where any pretense of simplicity ends. Not only do father and son appear as children in their own tales, they materialize in each other’s stories as shadowy influences hovering in the background, or at times, stepping forward and playing the roles of antagonist, shape-shifter, babe in the woods, savior. It is as though they have positioned themselves in a funhouse hall of mirrors, so that we get to see multiple sides of them, even as they––as narrators––attempt to contain our attention to the story at hand. This strategy allows the Müllers to take full advantage of the inherently unreliable nature of their first-person narratives and help the reader recognize the wolfish, the prismatic, aspects of their tales.

Eric Müller, the father, begins his story in rural Switzerland, where he rides crimson gondolas and tramps through wintry forests, before moving to South Africa where he encounters a phantom horse that forces him to consider his own mortality, hunts pheasants in Zululand, and befriends a thuggish young classmate whose mother feeds him a rich, oily soup that turns out to be swimming with chicken hearts. Yet despite the sly, fairytale quality of Müller’s prose, a ribbon of grim realism persists throughout. In one of the book’s most unsettling stories, he watches as two schoolmates torture squirrel-like dassies on the savannah by stabbing them and yanking the slick ropes of their intestines out and gleefully waving them in the air. Afraid of being shamed by his peers, the child pretends he isn’t troubled by this brutality, which we recognize as his own version of crying wolf. Even so, the wolf sinks its teeth in our narrator’s hide. “Two more suffered the same fate before we returned to the farmhouse. I felt guilty and sickened by the hunt…one thing I knew for sure, it would be a long time before wars would be eradicated on this earth.”

August 8th, 2014 / 10:00 am