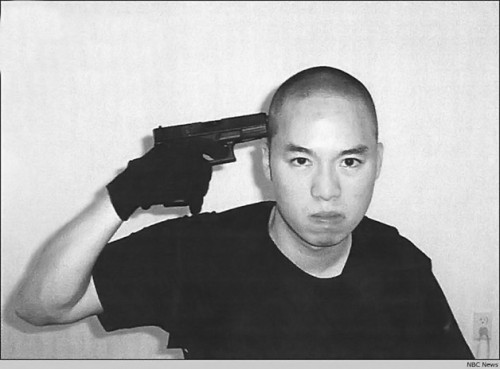

Boys Who Kill: Cho Seung-Hui

The next installment of Boys Who Kill stars Cho Seung-Hui, or Seung-Hui Cho, or Question Mark. On 16 April 2007, 4 days before the 7th anniversary of Columbine, Cho killed 32 people at Virginia Tech. First he visited West Ambler Johnston Hall, a dorm room for both boys and girls, where he killed one boy and one girl. Then he traveled to Norris Hall, a classroom building, and killed 30 more people.

Ever since Cho was taken out of his mommy’s tummy he hasn’t taken to talking. “Talk, she just him to walk,” says Cho’s great aunt about his mommy. “When I told his mother that he was a good boy, quiet but well behaved, she said she would rather have him respond to her when talked to than be good and meek.” At Virginia Tech, one of Cho’s roommates remarked, “I would see him walking to class and I would say ‘hey’ to him and he wouldn’t even look at me.” Other students concluded that he was a deaf-mute. He ate myself all by himself, and when someone offered him 10 dollars to say something, he said nothing. According to medical professionals, Cho suffered from “selective mutism.”

I, too, would prefer to be mute, and so, it seems, do other boys. Holden Caulfield dreams about being a deaf mute, and, it’s been reported by various biographers that instead of engaging in dinner table conversation, Arthur Rimbaud would just growl. Talking is terribly human — this race of creatures does in it grotesque quantities: they talk at Whole Foods, at overpriced bars, at trendy coffee shops, and, obviously, through Gmail, Gchat, texts, Facebook, Twitter, Disqus, and so on.

Cho’s contempt for normal communication distinguishes him from humans. Virginia Tech students and teachers constantly construct Cho as boy who confound expected human behavior. A professor labeled him “disturbing” and “unusual.” A student in his playwriting class said Cho “was just off, in a very creepy way.” According to Nikki Giovanni, students started skipping her poetry class due to Cho’s behavior . When Nikki told him to either cease composing sinister poems or drop her class, Cho replied, “You can’t make me.” Eventually the then head of the English Department, Lucinda Roy, tutored him privately. But even Lucinda was afraid of him. During the one-on-one tutoring appointments, Lucinda and her assistant agreed upon a code word that would prompt the assistant to summon security when uttered.

Based on this testimony, Cho is similar to a virus or a disease. No one wants to be around him; everyone is horrified of his presence. Not one to stay up into the wee hours of the morning to drink, party, and partake in sexual intercourse, Cho went to bed early and awoke early. He also played basketball alone. According to the New York Times, Cho was in a “suffocating cocoon.” (Being in a “suffocating cocoon” seems very dramatic and cosy; it also seems as if a “suffocating cocoon” would provide protection from mankind.) Virginia Tech journalism professor Roland Lazenby sums up Cho as a “shadow figure, locked in a world of willful silence.” Both Lazenby and the Times portray an incomprehensible boy who, isn’t free and liberated like Western subjects, but is held captive by a dark dangerous force. As Theresa Walsh, a girl who witnessed the killings in Norris Hall, says, “I’ve never really thought of him as a person. To me, he doesn’t have a name. He’s always been just the ‘the shooter’ or ‘the killer.'”

I DON’T “GET” POETRY READINGS

I’m a soon-to-be graduate of an M.F.A. program in creative writing. All I have left to do is teach a few classes, defend my thesis, and read a few books. Oh. And I’ve also been tasked to write a report on a poetry reading. This last point is why I’m writing to you now.

Let me backtrack for a moment though to tell you that before I was an M.F.A. student, I was an undergraduate working my way towards a B.A. in creative writing and a B.S. in advertising. Before that, I was a teenager that lived with my father, who was a professor, and my mother, who was an English major. My mother took her major very seriously, and as a result I began reading Poe, Melville, Plath, Tennyson, and other “canonical” writers at a very young age.

In short, I’m no stranger to poetry.

However, after going to the Hoa Nguyen reading at the University of Colorado at Boulder on February 21st, I realized that I don’t really “get” poetry. Or rather, I kind of “get” poetry, as much as it’s possible to be “gotten,” but I don’t “get” poetry readings.

After the reading, I confronted a friend about my dilemma: having to write a piece on something I don’t really understand. He recommended I read the VICE article by Glen Coco titled: “I Don’t ‘Get’ Art.” I ripped off the title, but what choice did I have when Coco said it so well the first time? Coco’s title is modest. It blames no one but Coco himself for his inability to “get” art.

There are others, however, who are more hostile towards poetry and its various, associated artifacts.

With the whole Lena Dunham Girls craze sweeping the nation, I thought I’d watch her film, Tiny Furniture. What particularly stuck out to me about the film was a statement one of the characters made about poetry. It went, “Poetry is a very stupid thing to be good at. Poems are basically like dreams–something that everybody likes to tell other people but nobody actually cares about when it’s not their own. Which is why poetry is a failure of the intellectual community.”

April 26th, 2013 / 12:00 pm