THE ZERO-DEGREE NOISELESSNESS OF DEATH: LECTIO I-IV

Speech may be a function of Logos, where rational compositions serve as cultural appropriation, or speech may serve a revolutionary, contestatory role by internally rupturing the structures of Logos at the very points of its own contradictions; screams and laughter may be reactive phenomena, resulting from the neurotic exigencies of life, or they may serve serve as rebellious eruptions of corporeal energy, heterogeneous outbursts of expropriation, where Logos is disrupted by the libido; silence may be the zero-degree noiselessness of death, where life itself is betrayed, or silence may be that moment where sovereignty is elliptically expressed as incommunicable inner experience.

In Medieval philosophy and theology, a lectio (literally, a “reading”) is a meditation on a particular text that can serve as a jumping-off point for further ideas. Traditionally the texts were scriptural, and the lectio would be delivered orally akin to a modern-day lecture; the lectio could also vary in form from shorter more informal meditations (lectio brevior) to more elaborate textual exegeses (lectio difficilior).

LECTIO I: Kate Zambreno’s Green Girl

LECTIO II: Horror vs. The Patriarchy

LECTIO III: Joe Wenderoth pushes the surface

LECTIO IV: The Dionysian Excess of Living

Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation & Kate Zambreno’s Green Girl

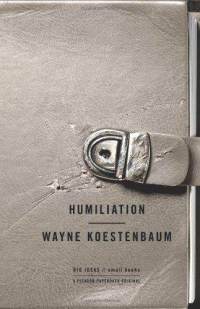

Just released from Picador’s “BIG IDEAS // small books” series is Wayne Koestenbaum’s 184 pp meditation on Humiliation, which I read in two 2-hour sits on a stationary bike punctuated with a few seatings on the toilet. It felt good to read this book in those places, which is often where I read anyway but don’t as often get to admit with relevance, but at last, here is a book in which those sorts of places might well be the center.

Just released from Picador’s “BIG IDEAS // small books” series is Wayne Koestenbaum’s 184 pp meditation on Humiliation, which I read in two 2-hour sits on a stationary bike punctuated with a few seatings on the toilet. It felt good to read this book in those places, which is often where I read anyway but don’t as often get to admit with relevance, but at last, here is a book in which those sorts of places might well be the center.

Humiliation operates in many ways at once. In short, numbered sections referred to as “fugues,” themselves cut up into numbered chunks of information, Koestenbaum goes forth into dissecting how the experience of being humiliated operates on a person, and therefore creation. The span of references here are quite wide, revolving quick enough to keep the brain moving as quickly as Kostenbaum’s dissective eye wakes each one up. From craigslist ads such as “HAIRY ITALIAN WANTS TO HUMILIATE A GENEROUS BITCH,” to Koestenbaum’s lurking in men’s rooms for encounters (and politicians caught inside the same), to de Sade and Artaud and Basquiat and Michael Jackson, and so on, the feed remains continuously engrossing in that way that all acts of humiliation seem to, publicly and privately, in spectacle, though here handled through Koestenbaum’s sharp and self-aware way of parsing act into idea.

“The reason I’m writing is to silence the deep sea-swell of my humiliated prehistory,” Koestenbaum writes, “a prologue no more unsettling than yours.” One of the major ideas explored here seems the matter of identity and experience that arises from the very act we work as people most ways to avoid: being humiliated. In each transaction there is the victim, the abuser, and the witness. Koestenbaum pulls off this weird shift of internal self-creation mixed with the experience of the other in an incredibly balanced method of veering back and forth between cultural commodity, confessional remembrance, and pointed commentary. A lot of questions are asked, moments are raised, allowing a kind of skin to rise up rather than some definitive proclamation of the idea. The book itself seems to both reveal and reveal and turn and turn, the way we might try to pretend to not be looking at something in the presence of someone else, though unable to fully look away. The moments of the facing, too, are powerful for how plainly they’ve been laid out. The book ends with a list in the spirit of Dodie Bellamy of some of Koestenbaum’s humiliating experiences: “My mother pulled a knife on my father, whose shocked aunt sat watching on a black leather chair. (The knife had a dull blade.)” or “A kid in seventh-grade gym, on the soccer field, called me a ‘wop faggot.’ I was flattered to be mistaken for an Italian.” The chain of small hells is both cringey, silently grinning, desperate, and wise. These things are laid out for us to take them, and this too becomes part of the machine, a kind of revolving door of do what you will with this, and please be kind. That at the same time Koestenbaum bares such skin he makes his subject so impossibly addictively paced and by turns tickling that it is impossible to put down becomes both a welcoming and a silent stab of implication: we are right here and he can’t see us and we can see all of this of him, which is the nature of the transaction of all making, and all taking. READ MORE >