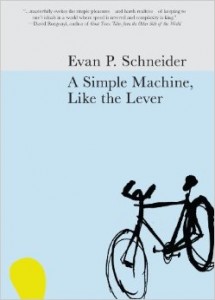

A Simple Machine, Like the Lever by Evan P. Schneider

A Simple Machine, Like the Lever

A Simple Machine, Like the Lever

by Evan P. Schneider

Propeller Books, 2011

179 pages / $14 Buy from Propeller Books or Amazon

I’m tempted to say all kinds of irresponsible things about Evan P. Schneider’s first novel: that it’s the Catcher in the Rye of our time; that it’s the book that saves leisure-time fiction with an eye to the fact that making money and trying to survive on that money is the primary substance of most of our lives; that “If There’s One Book You Read This Decade, It Should Be This!” If I said these things, I would risk being seen as engaging in the reviewer enthusiasm warned against here and here, which warnings, I would add, I agree with wholeheartedly.

But I loved this book. I think more people need to know about it. So what the hell.

A Simple Machine, Like the Lever is one of the very few novels I’ve sat down and read in a single sitting, not because I was planning to but because I couldn’t not. Catcher in the Rye is the other one. It may not be cool to say you like Salinger anymore, but his seminal novel affected the hell out of me, and probably you, too, back when you read it in high school English. Like Holden Caulfield, A Simple Machine’s Nicholas Allander is earnestly confused about the complexities of the adult world, plying his way through doomed encounters to a bare reconciliation of life’s ridiculousness with his own naïve ideals.

Unlike Holden Caulfield, Nicholas Allander is 31 years old, barely employed at a “fucking sink company,” and digging himself out of a huge hole of credit card debt while trying to retain the minimum amount of respectability necessary to hold a girlfriend. He is on a walk with said girlfriend, Marie, when he finds a paper cylinder of salt on the side of the street and picks it up to take home with him. She says:

“Can I tell you something?” Marie dropped my hand and stopped walking. “When I watched you pick that up I thought to myself, ‘He can’t possibly eat that. There’s no way.’ But I didn’t say anything because I know that’s what you do. That’s how you are choosing to live.”

Nick is nonplussed. The conversation turns to where they’re going, as a couple. How Nick has to start taking better care of himself. But how he lives is not really a choice, he insists.

“I hate being in this position,” I said. “It feels ridiculous and embarrassing. But I am, and I have to make sacrifices. If it makes you feel better, when I get home, if the salt seems bad or whatever, I won’t use it.”

“Jesus,” Marie said softly, “it’s not about the salt.”

This kind of dialogue is what makes the book so compelling. Nick is so consumed with doing what seems right—paying off his debt once and for all, mostly—that he can’t understand the secondary social constructs of a world that has been designed for folks who have moved past that point. The image of the cyclist here an apt one: if you’ve ever commuted by bike on roads thrumming with giant cars, you’ll know the feeling of being left behind by the petroleum winds of an infrastructure that is not built for you.

It’d be easy to get preachy, here. It’d be easy, in a book about being poor and riding a fixed-gear bike around Portland, to make Nick into your proverbial hipster, trying desperately to find meaning in a world that is clearly devoid of it by fitting into a developed “alternative” culture. But Nick doesn’t ride the kind of bike “so many young people ride these days”; as for its fixed gear, it just came that way. He does a circuit of push-ups and sit-ups and desk-chair-curls in his apartment after work, to try to stave off the love handles. He’s not even trying to find meaning, really. He just wants keep up his relationship with Marie and get through every day without staining his work pants with bicycle grease.

This all works through a very particular narrative voice, one of observation and calculation and gentle confusion at the world’s complexity. But this does not mean Nick is cold. His visions of the city in autumn, usually from the saddle of his bike, are stunning.

Why can’t it take longer, the amazing things, such as leaves falling into my path as I ride? Like weightless gold coins, they tumble back and forth, to and fro, down and down, and then somehow land right in my wire basket as I’m on the move. I’d like to stay in these moments. I want to see them all the way through until they’re gone for sure.

There’s something childlike about Nick, something uninitiated that allows us to see the world for as cruel as it is and as beautiful. We need him, accustomed to it all as we are, to remind us of the sense of frustrated wonder we had back when we loved Catcher in the Rye. We need A Simple Machine, Like the Lever, to remember what it feels like to go somewhere, everywhere, only under your own power:

The movement, the shush-SHUSH, shush-SHUSH, shush-SHUSH of my pedaling up and down, pumped blood to parts of my body I swear I hadn’t felt in years.

***

Dennis James Sweeney‘s recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Fractured West, Sundog Lit, Whole Beast Rag, and Word For/Word. Find him at dennisjamessweeney.com.

November 29th, 2013 / 12:00 pm