Plays/For Theatre by Kieran Daly

Plays/For Theatre

Plays/For Theatre

by Kieran Daly

bas – books, 2011

44 pages / $10 Buy from bas – books

The genius of the plays in Plays/For Theatre is that they offer almost nothing of anything you’d expect from any kind of play. There are some precedents here in Stein and Beckett in their starkness and refusal, but Daly’s plays inhabit a kind of literalism that avoids both the wordplay of Stein and the ghostly psychodrama of Beckett’s shorter works, even Breath, in which the lights rise to the sound of an inhalation and lower to the sound of an exhalation.

Daly’s work is even more spare than that, usually absent of any kind of staging or even characters unless generic actors are referred to peripherally. What you get instead with Daly’s work is him stretching the form of the play so hard over content completely unsuited to drama that it eventually becomes tough to even read the plays as plays. They’re more like the cadavers of plays, taken out of cold storage for study by students not of the theatre but of a kind of literalism that would make even nouvelle roman writers blush.

Take, for example, the play Gender Trouble by Judith Butler: a Play in its entirety, lack of italics (sic):

ACT.

[Entire text of Gender Trouble by Judith Butler.]

SCENE.

Gender Trouble.

SCENE.

Gender Trouble by Judith Butler. Published 1990.

ACT.

The book Gender Trouble by Judith Butler.

And that’s all you get. The book is dramatized, but not by being reworked through character and setting, but simply by being placed as an object within the form of a play. Most of the plays in Plays/for Theatre behave this way; there are plays about corners, windows, A Thousand Plateaus, numbers, and Law and Order: Special Victims Unit (Season Five) among other things. And while Daly works subtle variations into his presentations, the forthright literalism remains intact. The play about a window is literally that and nothing else.

September 20th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Propagation by Laura Elrick

Propagation

Propagation

by Laura Elrick

Kenning Editions, Dec 2012

106 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon or SPD

The poems in Propagation might seem quiet at first, or early on in the book, consisting mostly of simple phrases restated again and again with different line breaks, subtle emphasis shifting in language we might otherwise overlook, and while that might be true in some cases, don’t be fooled: these poems are loud shouts and angry jokes, raucous and just as ready to hit you as to be read. And this is a good thing during a manufactured crisis in poetry having to do with affect and identity and stuff you already know about if you’re all conversant with what’s going on in the poetry teacup right now.

What’s great is that all that stuff is beside the point. Delivered in a deadpan lateral slide that manages to recall both Gertrude Stein and Larry Eigner, Propagation is a defiant book, ready to just provide you with language you’ve taken for granted and let you figure it out. Again, this is a very, very good thing. Propagation doesn’t so much present with you with poetry to appreciate or interpret as it presents you with words and phrases cut mostly like chunks off vernacular language and just offered, take it or leave it, life for example the following excerpt from an untitled poem:

this is really

thanks thanks

this is

this is

really this

is thanks

I’m

thanks and you

and you

and you

and you

thanks

this is

thanks

and you

So what’s above is both devoid of content and overdriven with it: devoid because we as readers don’t “get anywhere” beyond a stutter of I, you, this, and thanks, and overdriven because the more insistent the excerpt gets at connecting “you” and “thanks” the more sinister it seems, as if the thanks might be forced or insincere or desperate or all three. Many of the poems here work like this: what seems wan gets pounded home with great force until something as ephemeral as a thank you lands in a constantly shifting territory between and I and a you that don’t need to be named or described because it’s not them that matter it’s the gesture trapped in the stammer.

And as deft as Elrick is with empty generalities, she’s just as good with the kind of local and particular that you might be looking for in a “normal” poem, as in the following excerpt:

bio fuel

cardmoms want

to know why this svelt pixie

is cutting the floor to pieces

why you approach on impulse

asking why

she danced with two knives in the hallway

circling her intensity and anguish

which has something to do with Tecumseh (?)

vaguely but it does why

this girl is stabbing her kidney

do you want

the highest stiletto

no

the best speech

wicked smartness

want the schooling

(you said you did in the application)

September 9th, 2013 / 11:05 am

Plural by Christopher Stackhouse

Plural

Plural

by Christopher Stackhouse

Counterpath, Nov 2012

64 pages / $14 Buy from SPD or Amazon

It wouldn’t be wrong to call the poems in Plural slippery: content just eludes you, as does the floor plan of a consistent or memorable form. Stackhouse has a playful but terse and lateral style that leads you to wonder why most poems start or stop where they do or aren’t combined. Two careful reads didn’t reveal many clues for the reader so, like I mentioned, while the book is interesting in synopsis form the individual poems stay slippery, just out of reach.

And to present the book in synopsis form: Plural incorporates poems in the same tone but different formatting strategies, notes from art world lectures that are interestingly similar to the poems, and a movement across the course of the book from being concerned with the mind and consciousness to reveling in the body. The lecture notes are actually some of the most interesting parts of the book because not only do they give the surrounding poems context, they serve as a map for Stackhouse’s cognition. And although the notes are about primarily visual art, a lot of what Stackhouse notes bleeds into not just his writing but the idea of writing, as in “Notes from Panel Disc. @ The Fish Tank Gallery”:

The artist takes a position based on how s/he sees itself in

contextual dialogue (art historical?) with the human condition.

The artist interprets his/her world to create meaning, or/and,

comment on the way meaning may be transmitted.

Those last two lines are important as applied to Stackhouse’s mostly brief poems, which seem more concerned with transmitting meaning than creating it and lack much broader context other than being in the same book. This is not a bad thing; if you’re looking for lots of meaning consult your local public library for probably a few dozen books of free verse heavily into creating meaning, for what it’s worth. But the poems arrive with the same matter-of-fact record-keeping as the lecture notes, which can render them frustrating at times not because you’re desperately searching for meaning but because you’re wondering, given the consistency, “why X and not Y?”

An example of the bulk of the book follows, from a poem about midway through titled “Chew the Candy”:

from a crack in the concrete laid in an alley brutal

but potential for a lawn. Lounge there easy.

Find the line and then straddle it. Stroke the pole.

Probe the hole. Be comfortable in all that is not

there.

August 26th, 2013 / 11:00 am

OUT OF NOTHING #[0]; Or, blurbing the whole cacophony

[out of nothing] #0: theoretical perspectives on the substance preceding [nothing]

[out of nothing] #0: theoretical perspectives on the substance preceding [nothing]

Ed. [out of nothing], October 2012

144 pages / $12 Buy from Amazon or Createspace

When the opportunity presented itself to review the printed edition of [out of nothing] recently, I jumped on it quicker than anything I’ve jumped on since I was ten. The idea in my mind wasn’t even necessarily to “review” OON but just to be able to hold the thing in my hands, first and foremost. [out of nothing] and Lies/Isle are obsessions of mine of late—the online versions, that is; these strange permutations of art and thought and science and everything intellectually captivating you could imagine organized into endless mazes of online content. If we’re to believe in such a thing as collaborative arts on the internet, this, in my opinion, is the sort of thing heading up the effort.

So anyway, I immediately requested a review copy of [out of nothing] and when it reached my house I felt connected to something likely akin to movements in the art scenes of New York in the 70s and 80s or Berkeley and various Western lands in the 60s. Here was the personification of serious writing and art in the twenty-first century and here was my opportunity to consider it. To be sure, considering it is likely the greatest feat I’ll here be able to accomplish. I’ve tried over the past few months to conceive of items to potentially submit to a publication like OON and I can’t for the life of me make it happen. Perhaps it has something to do with the collaborative nature of the thing, perhaps the three editors and founders of OON are just that-fucking-savvy that they’ve managed to push the intellectual envelope even more, I’m not sure. All I know is, if The New Yorker was once taken (dreadfully) seriously as a hub to receive one’s culture, [out of nothing] (both the print and online version) is its strange twenty-first century cousin doing bizarre rituals/experiments in the city’s basement trying to reanimate the corpse of Soren Kierkegaard.

But I digress:

Considering the structure of this anthology, I’m going to move through and evaluate each piece in order with as calculated a response as I can muster. This being an anthology of the highest order, my efforts as critic of OON will be best if the responding structure of my own writing not attempt the strange collective genius inherent to that which I’m writing about. I featured the subtitle “blurbing the whole cacophony” to draw comparisons with Melissa Broder’s piece “blurbing every story in the new New York Tyrant,” because it’s helpful to have something to riff off of this time of year, when the mind slows down and wants only to recoil into hours of sleep. O sleep.

(Furthermore, given the array of materials that exists within the 144 pages of OON, the length and style of my interpretations will vary, and where my words will surely fail to illustrate the images/texts and their substance, I’ll include scanned images of pages because I’m not beyond that and I love this fucking thing too much to assume to understand it.)

Now, regarding the introduction:

IS THAT ALL THERE IS?

by Jon Wagner

Reading this, I’m reminded of something Rick Roderick says in his lecture regarding the works of thinkers like Foucault, or Habermas—and one could easily expand this to Deleuze, or even Derrida if one was so inclined—whose works can hardly be called “philosophy,” in the traditional sense. He goes on to emphasize that contemporary “thinkers,” must encapsulate more of society than was previously expected of philosophy, and that the greats like Foucault or Nietzsche must be acknowledged as something else to be understood. Not only can Wagner’s introduction not be called an “introduction,” in the strict understanding of the word, but it belongs alongside the works of those aforementioned thinkers as something transcending mere criticism, philosophy, history, geneology, ontology; the list goes on. What’s given here is first a consideration of the idea of [nothing],’ and what the bracketing of the word/idea itself might mean, then an introduction to the proceeding texts is given and it’s briefly explained that commentary will be provided by a handful of “Jabberwocks,” along the way—“Benjamin, Baudrillard, Derrida, and Kierkegaard. This is something I’ve not seen done, like, ever, and in addition to creating this extremely fun intertextual environment while reading, it brings to mind all kinds of questions about the apocryphal, marginalia in general, and ghosts. My own thoughts here channel and mimic Deleuze, Pasolini, and Miss Peggy Lee within a restricted economy of expression that bleeds a general excess in the very effort of constriction.” I.E. OON does not seek to be a mere anthology, nor even a mere physical book, and will go so far as to resurrect the dead in texts to bury its collective mind in the concepts of nothingness as deeply as possible. This is unlike anything dubbing itself an anthology that I’ve yet experienced, and onward we must go.

PRE-WAR

Nicholas Grider

I’ve wondered a great deal lately about the idea of a text somehow avoiding the idea of a start and finish entirely, and bridging the gap towards something more diffuse. One thinks of Joyce in this regard and Finnegan’s Wake, or perhaps something more contemporary like Lost Highway, but even still these things do have a beginning as far as location is concerned (the “first” page, the “opening” of the film). I’d feel safe in positing that Grider’s piece comes close to achieving this rather timeless sensation. Although the writing only runs across three pages, the blend here of Walter Benjamin’s and Jean Baudrillard’s insights with the author’s own do lend an eerie, spectral air to the thing and that tied with the fractured indentation of Grider’s lines tempted me to read the thing out of order, forwards and backwards; as many ways as I could considering its brevity. I won’t begin to argue that we’re a great deal closer to printed texts that could actually be called diffuse in this regard, but this first in the anthology does seem to chip away at this idea. I’ll include here the interplay between Grider and Baudrillard, without question my favorite moment in the piece.

“or you have better things to do, you are a background character who laughs a little too long at the funeral parlor with 2.5 walls, you can do a lot of things with flashcuts these days, jackknifing, binge drinking, shoplifting, heavy breathing. {}

{Indeed, you can, when the reified even it so much so that a single marker can indicate an

entire conceptual package: an action, a life, an historical trajectory. JB}”

READ MORE >

May 8th, 2013 / 11:00 am

How to Review Vanessa Place’s Forcible Oral Copulation

Parrot 11: Forcible Oral Copulation

Parrot 11: Forcible Oral Copulation

by Vanessa Place

Insert Blanc Press (Parrot Series), 2012

18 pages / $9.00 Buy from Insert Blanc Press

1. You could just write a short summary of the chapbook, which is artfully arranged and darkly comic legal testimony of, no surprise, forcible oral copulation. You could mention that it’s part of Insert Blanc’s Parrot series, provide an excerpt like the one below, and write something to the effect of writing a review of Strict-Lift Conceptual Writing is sort of like writing a review of a rock: is it a good rock? Does it fulfill its implicit goals of being a rock? And so on.

When asked if he orally copulated his victims, appellant said he hadn’t; when asked if he’d forced his victims to orally copulate him, appellant said he hadn’t; later, appellant said maybe he had.

2. You could breeze through description and head straight into a discussion of Strict-Lift Conceptual Writing (henceforth SLCW), outlining the history and current state of it and then providing your opinion of it, writing maybe that unlike the more engaged conceptual writing found in great books like I’ll Drown My Book SLCW is sort of like the kind of joke that’s only funny the first time. The novelty wears off yet you keep hearing the same joke and you’re too bored to laugh so the joke-teller tries to confront you with titillating and/or shocking subject matter and you yawn because SLCW is SLCW is SLCW.

3. You could breeze through points numbers one and two and throw down a gauntlet maybe something like Forcible Oral Copulation would be right at home on Paul Ryan’s bookshelf next to his Rush Limbaugh books because SLCW is inherently neoconservative in its negation of creativity, complexity, and pleasure in favor of dumb objects. SLCW the opposite of Conceptual Art’s dematerialization, a fetishizing of the material and content-free vs. anything remotely avant or provocative, and you could maybe say that SLCW is not going to hurt you but it’s sort of like trying to swat a dead fly with a completely numb arm. You’d go on to shore up your dragging in of capital P Politics by paraphrasing Adrian Piper’s statement that all art is political, whether explicitly or implicitly, and you’d compare the production of SLCW unlike thrilling freeform conceptual writing as a shutting down of possibility, a reduction, conservatism in the literal sense and so in the political. Or maybe you’d avoid politics because SLCW is maybe the it-girl of the 21st century alt lit scene and knocking it would be like yelling back at the television in a room full of people who want you to shut up and just watch like a reasonable person or else leave quietly.

4. You could talk about your history as a rape survivor and wrap your discussion of Forcible Oral Copulation around its ability to do anything other than function as the outcome of an idea, simple curation that puts you on edge even though you’re supposed to be clinically distant and Over It anyway.

5. You could zoom through points one through three and go light on the politics in favor of discussing why conceptual writing, along with The New Sincerity, are relics of Bush-era willful ignorance because both SLCW and The New Sincerity are not sincere but naive in their fumbling mimicry of something past or lost and serve the purpose to present a literary angle of attack that reduces literature to something fundamentally unchallenging and unnecessary. You could maybe bring politics in at this point but maybe not.

December 17th, 2012 / 12:05 pm

[BOND, JAMES]: alphabet, anatomy, [auto]biography

[BOND, JAMES]: alphabet, anatomy, [auto]biography

[BOND, JAMES]: alphabet, anatomy, [auto]biography

by Michelle Disler

Counterpath Press, 2011

120 pages / $14.95 Buy from Counterpath, Amazon or SPD

Superficially [Bond, James] is an exploration of the Bond character as he appears in Ian Fleming’s novels: rescuing girls, thwarting villains, escaping from dangerous situations, and smoking a ton of cigarettes. What’s fascinating and brilliant and great about the book, though, is that we get this exploration and some rumination on the masculinity it represents not in standard linear nonfiction prose but as a series of lists and games and experiments. This makes the book worth your entertainment dollar in a variety of ways: as an investigation of a popular icon/fictional character, as a look at what represented the summit of masculinity 1953-1965 and how the ideal is shored up through the use of women (and villains) as disposable props, and as a really stunning example of how brilliant innovative nonfiction can be when it’s not afraid to take a lot of risks.

And the book does take risks. Divided into the three sections of the subtitle, the text never offers a moment of scholarly distance but instead offers you a spread of cross-sections of Bond as character and as archetype. In the first section, alphabet, you get just that: an alphabet comprised mostly of lists of common people, objects and events in Bond’s world. For example D is for “Dislikes” and you get a two-page inventory of things like the following:

October 29th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

On Poems On

On Poems On

On Poems On

by Sandra Liu

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012

28 pages / $8 Buy from UDP

Even though there’s nothing particularly insular or fragmentary about Sandra Liu’s work, it’s still difficult to grasp exactly what’s going on in the book because of the restless nature of the poems’ wanderings through landscape, experience, character and image. Nominally this is free verse written in standard syntax, but individual lines or sentences in Liu’s poems aren’t trustworthy indicators of what might come next. This is always a good thing, because the unpredictability adds to the poems’ allure and as I read through the chapbook I found myself drawn closer and closer to whatever sharp turn the poem might next, unless there’s no sharp turn or the poem cuts off abruptly. The poems in On Poems On are a ceaseless lateral movement along or between landscapes either literal, linguistic, or informative that leave you with a sense of having visited a location or moment without being allowed to linger long enough for details of daily life to become mundane.

This isn’t to say that the poems are particularly wild, save for the punctuations throughout the book of often deadly violence; the work is measured and light, and could pass as graceful observational poetry if there weren’t more at work, like the aforementioned violence. A good example of this is “Static,” in which dryly delivered information about the geography of and south of Indonesia is woven together with scenes of rioting crowds gunned down by state forces:

archipelago, grenades, AK-47s,

household bombs and machetes alternate with an underwater

topography, flats of nadir in several areas of the city and extended airscaping

ridges

leading to Halmahera,

itself comprising four peninsulas, each,

a 12-year-old boy, drawn out by congeries of islets,

traversed by SUV.

October 12th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Marjorie Welish: In the Futurity Lounge / Asylum for Indeterminacy

In the Futurity Lounge / Asylum for Indeterminacy

In the Futurity Lounge / Asylum for Indeterminacy

by Marjorie Welish

Coffee House Press, April 2012

112 pages / $16 Buy from Coffee House or Amazon

It says a lot about Marjorie Welish’s new collection of poetry that the cover design of the book consists of well-known writers hard at work both explicating the book and extolling its virtues. The book doesn’t really need that kind of push in terms of quality (line by line, the writing is great throughout) but explaining what Welish’s project consists of is more of a problem. Reading the book, when you try to corral the abundance of subjects addressed in the book into a good read and interesting network of ideas, you’re often interrupted by uninvitingly plastic stretches that may test your patience not because they don’t add up but because Welish’s “not adding up” isn’t an interesting and compelling kind of resistance.

Subjects and abstractions that recur and are addressed from different perspectives across the span of the book include but are not limited to: architecture, modernism, the language of public space, language as a faulty reproductive device, proscriptive language, performance, mechanical technology, outmoded technology, Brecht, Beckett, Stein, Shakespeare, Baudelaire, translation, the pragmatics of the visual art world, and Dada. These aren’t just jumbled together, however, so much as continually revisited in widely varied forms. And with the press materials in hand, there’s even more: the book is actually two books, the first being a “laboratory of modern futurity” and the second “a zone of research” responding to choice terms from translations of Baudelaire’s “Correspondences.” It’s not hard to imagine, then, how the book could labor under the weight of so much content even as the poems themselves are compelling moment by moment.

What more effectively ties the individual poems together is the very creatively employed use of repetition and rearrangement. The poems often proceed not via an attempt to directly address or explain any of the more abstract ideas mentioned above but to perform them and move sideways through varied repetitions and a reliance on all caps and homophones. One of the more concrete examples of this appears in “Signal to Noise,” which begins like this:

Bathe her and anoint her in oils, permit her to feast. Then interview her.

Then interview her

Ask her name and from whence she came. Then how she came to this pass.

This is a test.

This is a test.

END.

and quickly transforms into complex expansion:

Then interview her.

SENDER is to issue a few central questions in advance to structure the interview to allow

the SUBJECT a chance to think—I do not believe in provoking the stranger to tilt some

sort of misguided spontaneity in flight! HELPER may indeed issue three or four

questions also and ours, kindred may overlay. Infer her. Test test test test coincidence

of number emitted in collapse.

You’re not arriving at an increased understanding of the nature of either “SUBJECT” or questions but rather you’re shown an increasingly baroque set of variations that address the natures of an interview and a test as well as a play on words that spreads from interview her to infer her and (tacitly) interfere. This is how much of the book does the heavy lifting of addressing such a wide cast of content—by variations that illuminate the importance of minor linguistic differences and by playing around with those differences.

This play, and an attendant “subject” or place or thing, are what gives you mooring in the midst of all the complex abstraction, knowingly referenced in lines like these:

More specifics

legible, capable of being read charismatically, if unintelligibly writ

or written intelligently lenient despite indistnctness or obscurity

since reversed: inverted involved upside down scrambled sampled and

put through a sieve crushed with the blade of a knife cubed

and quartered split off from plaintext

The problem is that “plaintext” gets left completely unmoored for much of the book, which is compelling line by line but doesn’t accrue into any kind of broader perspective on any of the subjects named above or connections between them. That’s the main, and really only, problem of the book: the noise of abstraction is beautiful, but after dozens of dense pages it starts to seem repetitive and feel dull. This is not to say that the book itself is dull, but that the sheer tonnage of poetry crammed in a small font into 97 pages eventually makes the work of playing along much less appealing to do unless you’re an adept at the wide range of references Welish employs (from Frank Lloyd Wright to WWI to a Bob Perelman poem) or else read strictly for surface play rather than any kind of larger architecture.

No single line or poem is flat-footed here, but it’s the weight of unplacable reference and dodge into abstraction that makes the book tough as a straight-through read. Instead the book invites visiting it here and there, piece by piece, reading enough to see the intelligence and wit at work but not so much that the poems’ frequent indeterminacy begins to frustrate or bore. As the book title even suggests, In The Futurity Lounge is less a place to stay than to visit and hang out for a while before moving on, interested in visiting again.

***

Nicholas Grider is an artist and writer whose artwork was recently the subject of a solo show at the Armory Center for the Arts in Los Angeles and whose writing has recently been published in Conjunctions, Drunken Boat and other journals.

July 13th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

I’LL DROWN MY BOOK: Part 3

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

Edited by Caroline Bergvall, Laynie Browne, Teresa Carmody, & Vanessa Place

Les Figues Press, 2012

455 pages / $40 Buy from Les Figues Press

(Disclosure: I honestly had no idea when I requested the book but note that it contains the work of some of my friends, acquaintances, teachers, mentors, and personal heroes, though the widescreen approach in curating the book’s 64 writers works against me simply cheering on a select group or writer to whom I’m personally attached.)

Prior to reading I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women, my general, sloppy idea about conceptual writing was that it was only the kind of writing where the experience of appropriated text as object/concept was more important than the experience of reading what’s been sculpted into book form for “literary” value. Instead, I’ll Drown My Book offers approaches to encountering and writing text as various as the writers included and as familiar as “appropriation,” “intertextuality,” “hybrid” and “constraint,” named in the book alongside “dissensual,” “baroque,” and thirteen other broad categories as forms conceptual writing might take.

What’s important and unique about the writing in I’ll Drown My Book isn’t what strategy is being employed but the fact that there is a strategy, and often a structure. (The two being different in that strategy involves an approach guided by a given or created set of rules while structure involves use of a given or created form other than a continuous or broken line.) You could claim that all writing is strategic in some way with respect to what decisions you make when you set out to write anything but the writing in the anthology is strategic specifically because the strategies are local, formal, and often overt vs. obscured from the reader. Conceptual writing, here, is not a movement but a methodology, a way of viewing writing as always following and rewriting a myriad of different kinds of other texts, or by replacing “writer” with text. Just for the sake of contrast I’m claiming the nominal state of what let’s call “normative” writing is that you can and do claim sole authorship,over additive and usually linear text, starting off in your headspace with an idea or image or voice that seems worth pursuing and building on it alone, meaning, in the words of Frank O’Hara, you just go on your nerve.

June 6th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

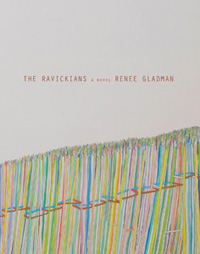

A Voice of Leaving: Renee Gladman’s The Ravickians

The Ravickians

The Ravickians

by Renee Gladman

Dorothy Project, 2011

168 pages / $16 Buy from Dorothy Project or SPD

The second volume of a trilogy of novels exploring the crumbling, war-torn imaginary country of Ravicka, The Ravickians is less an exploration of the people and culture of Ravicka than it is a breathtaking book-length meditation on loss. The book moves through what it means to be lost, to get lost, to lose connection with your fellow humans and surroundings. This is all done in a brief novel divided into three parts: 1) a first person account of a day spent wandering by The Great Ravickian Novelist Luswege Amini; 2) a poetry reading that same day given by Amini friend Zäoter Limici; and 3) 52 pages in twelve sections of unascribed dialogue spoken during a night out in the broken down capitol city of Ravicka that includes Amini, Limici, other writer colleagues and some new characters not mentioned earlier in the text.

May 21st, 2012 / 12:00 pm