I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying

I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying

I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying

by Matthew Salesses

Civil Coping Mechanisms, February 2013

138 pages / $13.95 Buy from Amazon

Koi fish have hundreds of scales that form a protective armor around them. Matthew Salesses’s I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying is a collection of 115 flash fictions that, like those scales, explore the spoken and unspoken nuances that connect and glue relationships in all their misfit forms. Many of the characters go unnamed, a decision that suggests that the companions symbolize divergent desires. There’s the wifely woman who’s his main lover and there’s a “white woman” who acts as a mistress as well as another Korean woman who is in place “for emergencies.” Each serve a different need, though none can satisfy him because he partitions himself like the segmented chapters that comprise the book. They are lyrical segments akin to jazz solos forming a striking concerto of prose. The impetus that triggers the journey of the book is the appearance of a son he never knew he had. When the boy’s mother, an old lover, passes away, the narrator takes the son into his home. Rather than a definitive reaction to this revelation, there’s a miasma of conflicted emotion, an uncertainty that could best be summed up in the piece, “She Was a Tsunami to His Earthquake:”

His lovers, his co-workers, and finally, his son, form a tenuous thread that bind the invisible wavelengths of his life together. Only, he is always trying to split them apart and keep them isolated in a delicately stratified web. In describing the side girl-on-the-side, he says: “I had to be careful with her, though I wasn’t technically married, because she collected the crumbs of truth, but for an hour with her, I was someone else, and when I left, I could discard that part of me and know it would be repossessed.” The elegance of the book lies in the poetic congruence with which his life is shattered by circumstantial incongruence. Say, for example, his observation at an art gallery with his son that only the letter T separates the word “paint” from “pain.” This was an association formed from his failure to be the artist he aspired to be as a freshman in college. He is protecting himself from pain, but entering it willingly to try to teach his son something about painting. That contradiction of both being in the mural and trying to control it hints at the theme of a man all too aware of his foibles and flaws, but still is helpless to do anything about it. Twisted accents in his relationships add shades and make every interaction a layered strip tease, tantalizingly bare without showing anything essential:

May 17th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Donald Richie and the Japan Journals: A Tribute

Peter Tieryas Liu previously wrote about Donald Richie and his Japan Journals on HTMLGIANT (read the full review here).

And now this great video:

My Pet Serial Killer by Michael Seidlinger

My Pet Serial Killer

My Pet Serial Killer

by Michael Seidlinger

Enigmatic Ink, 2013

312 pages / $13.99 Buy from Amazon

Some people raise cats and dogs. Claire, the protagonist of Michael Seidlinger’s My Pet Serial Killer, raises serial killers. Caged within the pages of the book is the ‘Gentlemen Killer,’ his gallery of helpless women, and a whole panoply of cultural idiosyncrasies that seem strangely alien when viewed through the cool detachment of Claire. Claire is an experienced collector who dissects social rituals with the vivifying apathy of a biologist. I’ve read a lot of serial killer books in the past two years, most trying to differentiate themselves by latching onto a more unusual gimmick. My Pet Serial Killer distinguishes itself with a unique foray into the world of mass murderers that’s best encapsulated by Claire’s proposition to the Gentlemen Killer: “I support you financially. I give you a place to hide. I make sure you are never under suspicion of being what you really are, a cold-blooded psychotic killer (so hot), and, in return, you clue me into your process. You become mine.”

The prose flows in a conversational rhythm and her tone remains relatively level throughout, despite the fact that she is describing horrific scenes of murder. The macabre episodes are lent an especially disturbing tone because of the way Claire chastises her pet for not carrying out the murders in an optimal way. She treats him like a puppy gone awry and complains about him like an unruly boyfriend: “He doesn’t want instruction but, as master, I feel like I need to show him how it’s supposed to be done. He’s too lenient on method and MO. No wonder we find ourselves needing to find patsies covering our tracks every few girls.”

Interspersed within the narrative are italicized segments that are described as “optional” but provide deeper insight into the issues at stake and break apart traditional relationships. Targeted are friendships, classmates, strangers at parties, lovers, master and pet, and even reader and author. Claire refuses to reveal her name to Victor, AKA the Gentlemen Killer, who is a suave and dashing man that can woo almost any woman into bed. She’s less impressed by him, especially after her initial exhilaration dies down: “I’m quickly discovering he’s not much of a talker after he’s exhausted all introductions and quick casual lines. Everything’s practiced until he’s out of memorized and rehearsed material. He’s awkward at his most pure, and he’s incapable of matching my gaze when I’m still there looking for more… So I’m the one that has to tell him what to do. I’m telling him to go into his room.”

March 18th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

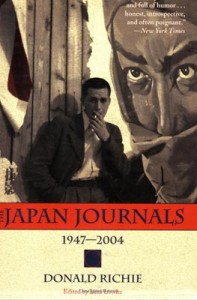

Donald Richie and The Japan Journals

The Japan Journals: 1947-2004

The Japan Journals: 1947-2004

by Donald Richie

Stone Bridge Press, 2005

496 pages / $18.95 Buy from Amazon

Donald Richie passed away on February 19, 2013. Many people knew him as the preeminent critic of Japanese film, bringing attention and exposure for directors like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu to Western audiences. “Whatever we in the West know about Japanese film, and how we know it, we most likely owe to Donald Richie,” director Paul Schrader declared. I became familiar with his work through his Japan Journals which was edited and compiled by Leza Lowitz, covering his life from 1947-2004. It’s a hybrid work that is in part autobiography, a compendium of Japanese culture, a menagerie of famous writers and directors, and a confessional. Richie first visited Japan in 1947 as a typist for the U.S. Civil Service and returned to stay, in part due to their greater tolerance of homosexuality (he was openly bisexual). What struck me about his writing were his keen observations that felt less like wordy descriptions and more like a cinematographer setting up a scene from a film. Take for example when he described the writer, Yukio Mishima:

“Look at Mishima, that casual wardrobe— the leather jacket the medallion on its thin gold chain, the boots, the tight trousers, and the wide belt. These create a cutout figure, an outline, and a recognizable icon. We can trace its lineage. From Hemingway to Brando and beyond, this image presumes virility.”

Or W. Somerset Maugham as an old man in 1959:

“The stutter is initially surprising. He is so very old, and stuttering is an affliction of the young. Even more adolescent seeming is that he apparently never accustomed himself to it. It still retains, after all these decades, the power to disturb. He remains embarrassed by it.”

Similar to the cinematographer, it’s the direction of the camera that highlights the perspective. Rather than painting with light though, he painted with his words. Richie knew how to craft a scene in a way that was not only entertaining, but gave us an unexpected insight into his subject. This often entailed taking famous figures like author Truman Capote or Nobel Laureate Yasunari Kawabata, and making them relatable and surprisingly human. He didn’t shy away from the negative nor the more sexual elements which he viewed without judgment or bias. As an expat, he was the outsider looking in, giving him the advantage of observer by being partitioned off. Surrounded by the rituals and societal customs of Japanese culture, it was probably as stark a contrast to his childhood growing up in Lima, Ohio as one could imagine. Even when he could reproduce their behavior perfectly, he stated with an air of accepting regret:

“I behave in the Japanese manner. I refuse something, have to be urged, I say I am wrong when I am not. This brings smiles and nods. But I am not seen as behaving “like a Japanese.” I am seen as behaving properly.”

March 1st, 2013 / 12:00 pm

We Bury the Landscape

Peter Tieryas Liu (and Angela Xu) made this video review adaptation of his review earlier this year of Kristine Ong Muslim’s We Bury the Landscape. Check it out:

December 31st, 2012 / 2:38 pm

A Return to Candide

Candide

Candide

by Voltaire

Norton Critical Edition, 1991 / 224 pages Buy from Amazon ($11.56)

Penguin Classics, 1950 / 144 pages Buy from Amazon ($11)

I must have had g-rated goggles on when I first read Voltaire’s Candide because I didn’t remember how violently twisted the book got. Published as satire in 1759, it attacked Leibniz’s idea from his Monadology that this world was the best of all possible worlds. History intertwines with fiction in Candide as the backdrop of the Seven Years’ War and a deadly earthquake in Lisbon that killed more than fifty thousand people fueled Voltaire’s rage. The religious men of his age, the ‘optimists,’ tried to comfort people with the idea that everything, no matter how vile, happened for a greater good as it was driven by a higher power. Dr. Pangloss, Candide’s tutor and an obvious caricature of Leibniz, espouses this belief and Candide carries forward it as a conviction throughout much of the narrative. Voltaire drills in his rebuttal with the violent imagery of something straight out of a Takashi Miike film.

Take for example, Cunegonde, the love of Candide’s life, as she shares her tragic story:

As horrific as this sounds, shortly afterward, they meet an old woman who assures them her misfortunes outweigh theirs. She used to be a princess until her betrothed was poisoned through chocolate. She was then carried off as a slave:

October 5th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

We Bury the Landscape

We Bury the Landscape

We Bury the Landscape

by Kristine Ong Muslim

Queen’s Ferry Press, April 2012

168 pages / $12.95 Buy from Queen’s Ferry Press or Amazon

If for one minute, I got lost in the galleries of Kristine Ong Muslim’s mind, I don’t know if I’d ever be able to leave. We Bury the Landscape is a collection of one-hundred ekphrastic works of flash fiction and prose poetry pieces that act as glimpses— better yet— conduits, into parallel universes constructed and inspired by a surreal, but brilliant, forge of one-hundred unique paintings. Visceral is a word that gets overused. But in this case, the text leaps off the pages, claws it ways onto your bones, gnaws and tears and embeds itself inside the cavities of your brain. Many of the stories are short and can be quickly read, but each of them lingers hauntingly as in, “The Taxidermist and the Girl Made of Dead Things:”

May 14th, 2012 / 12:30 pm