The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame

The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame

The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame

by Gengoroh Tagame, ed. Anne Ishii, Chip Kidd & Graham Kobleins

PictureBox Inc, April 2013

256 pages / $29.95 Buy from PictureBox

Passion is generally defined either as “any powerful or compelling emotion or feeling” or, within the context of personal relationships, as a “strong sexual desire; lust.” Strength & power are two words that dominate these definitions. Strength & power are two concepts that dominate the short, hypersexualized narratives of Gengoroh Tagame’s characters: strong, large & butch men dominating, fucking, & occasionally loving other strong, large & butch men.

In the world of manga, and especially in the imported consideration of such, there’s an abundance of yaoi stories that teen girls flock to, love, write fan-fic about: yaoi is a subgenre of manga that takes young, thin, often effeminate boys loving other young, thin, often effeminate boys. Clearly, there’s a contrast between this & what I’ve mentioned Tagame’s narratives hold above: thick muscles, thick cocks, heavy BDSM overtones–there is the occasional cross-generation ‘romance’ told by Tagame, but even the young boy shares a closer physic to a professional wrestler than the twinky waifs that populate yaoi.

Pierre Guyotat once remarked that he couldn’t write unless his cock was hard. Similarly, Tom of Finland once remarked that his best drawings occur while he’s erect. I have to imagine that the sexual narratives that overtake Tagame’s work drive their creator, as well, to sexual satisfaction. There’s a remarkable sense of erotic obsession that drives the work, moving from gang-bang fantasies to hyper-developed arenas of sadism. Sometimes, when there’s time for it to develop, a work develops a plot, often a somewhat complicated one considering the constraint of a number of pages. Sometimes there is less plot, but always there is a surge of powerful eroticism dominating each panel.

READ MORE >

July 5th, 2013 / 2:44 pm

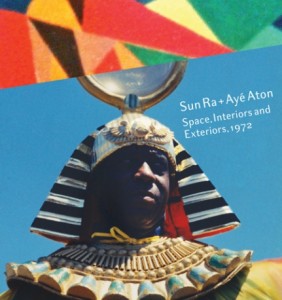

Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972

Sun Ra + Ayé Aton: Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972

Sun Ra + Ayé Aton: Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972

By John Corbett

PictureBox Inc, April 2013

112 Pages, $27.50 | Buy from PictureBox

Opening with several candid shots of Sun Ra donning full afro-futurist regalia in Oakland, filming the quintessential Space is the Place, Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972 finds Sun Ra himself in the foreground. An interesting choice, really, due to the fact that a large majority of the book focuses on Ayé Aton’s murals, painted primarily on the walls of Chicago’s south-side in the early 70s. But this choice makes sense, as the brief essay included in the book lets us know, as it was the overpowering figure of Sun Ra that brought a focus to Aton’s work.

Aton, who became a correspondent of Sun Ra in the early 60s (shortly after Ra moved to New York City), eventually joined the Arkestra, touring and recording with Ra during the Ra’s most significant span of recording, the years 1972-1974, when his most well-known album records was recorded, Space is the Place. Aton & Ra’s correspondence, in the beginning, was a mentorship. Aton’s curiosity towards many afrocentric esotericisms finding, if not answers, at least a response in Sun Ra (to see the breadth of the information that Ra poured into his philosophy, take note of this syllabus from a class Ra taught at UC Berkeley in the early 70s [as an aside: the environment of Berkeley where Sun Ra could teach a class like this is so far distanced from the current reality of UC Berkeley that it’s astounding], as recounted “by Arkestra drummer, Samurai Celestial, and others.”

Two brief essays in the book present this biographical (this mythical) information before treating the reader to a gallery of Aton’s murals, photographed, often obliquely, on Polaroid film in Instant film has never been the most archival film available; in these Polaroids it’s clear that colors have faded, that the precision of the film’s chemical reactions, etc, is far from precise. The material degradation adds a level of entropy to the aura the images create. While the introduction asks us to imagine rooms where entire walls are painted with fluorescent paint, the Polaroids reveal rough gestures in muted colors. With time everything fades.

But the suggestion, the consideration, is a fascinating one. As another essay points out, none of the photographs of Aton’s murals depict people in front of them, they are isolated in space, often even destabilized away from their position on walls, embedded in the flatness of the picture plane. In the late 1950s Sun Ra started calling his music “space music” because ” the music allowed him to translate his experience of the void of space into a language people could enjoy and understand” (Wikipedia). With these photos, the viewer is floating in a void of colors long faded. The dream is dead, and I wouldn’t be surprised to find most of these murals either painted over or felled with buildings during destruction.

My favorite mural, documented by a square Polaroid stamped with the month of “January” but bearing no year, finds a ram’s head above four staggering lines of grey, set within a large silver/white star-burst, across a field of pinks and oranges with black accents carrying through the field. The nothingness of the image plane is violated by a minor intrusion: that of a golden chandelier, hanging from a white ceiling. The reality of the murals becomes uncanny. This is a step towards a necessary mysticism, used by Ra and others to strive towards freedom, borrowing Egyptian symbols and steeping them in Biblical revisionism, a reality that allows the oppressed a sense of revolution. Space is the place, space is the place. The field turns into colors and every man and woman is wearing a costume that disorients. It’s after the end of the world–don’t you know that yet?

In 1968, Kenneth Anger visited the great pyramids of Egypt with a cavalcade of junkies, musicians, artists, and magicians. Costumes were brought. Anger’s greatest film, Lucifer Rising was filmed. Problems followed. The film eventually was released and has been recognized for its brilliance. Sun Ra, on the other hand, refuses to just make his film. The costumes were part of life. Life was revolutionary and within this revolt there was a refined aesthetic insistence. Aton’s murals carry this aesthetic insistence further, into the banalized reality of those who don’t have the freedom to live in Sun Ra’s world permanently. The murals serve as a reminded.

June 11th, 2013 / 11:27 am