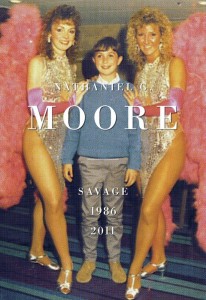

Savage 1986-2011 by Nathaniel G. Moore

Savage 1986-2011

Savage 1986-2011

by Nathaniel G. Moore

Anvil Press, 2013

256 pages / $20 Buy from Amazon

“If I had to write a will, it would only fill a matchbox flap. But a self-involved snuff letter would occupy months of effort, filling thousands of Bristol board sheets on both sides: the meticulous marinating of my family’s kamikaze descent.” With these tattered lines Nathaniel G. Moore takes us on an exhilarating tour of life in the strangest, coldest, and most depressing of families, set in the city that recently brought the world Rob Ford, packaged (according to Wikipedia) as a New Order box set. (Note: each chapter save for the prologue is named after a song by the post-punk electro band).

Set between the summer of 1986 and the late spring of 2011, the book unevenly chronicles, with an honest treatment, the rise and fall and (attempt at reuniting) a middle-class family from the suburb of Leaside in Toronto.

When Nate, a messy, lusty, mouthy yet anxious kid turns twelve years old, his father takes him to a wrestling match where he sees Randy “Macho Man” Savage live for the first time. (It should be noted that at the match, Nate is a fan of Ricky Steamboat and wants Macho Man to lose. This attitude towards the titular wrestler of course changes drastically in short order.)

Early on, the teenage fumbling of Nate and a friend named Andrew turn into a suggestive game of power and what appears to be, an area of interactions between exploration and abuse or a hazing. Yet their friendship seems to be the only non-family, non-fantasy thing in Nate’s life. At one point in grade nine, the narrator says, “Andrew was quickly becoming my whole world.”

Another factor contributing to Nate’s fear of isolation is the departure of his older sister Holly to university. As Nate says goodbye to the nineteen eighties and its Kodacrom of idyllic summer bike rides, swimming pools and erections, the nineties comes in with a bang of economic woes, family blows and dying grandparents. Holly’s returns on weekends are fuzzy, hungover interactions that play out in tender vignettes between slowly estranging siblings.

When Nate’s maternal grandmother dies during his last year of high school, his nostalgia kicks in at high gear the day of the funeral. “I urged everyone to watch the last known footage of Grammy, at which Uncle Carl waved me away, suggesting it wasn’t the time. That was it: she was gone.”

While Nate conjures up wrestling fantasies to portray his intense friendship with Andrew, the fantasy is not reciprocated, tolerated or understood. Soon Andrew withdraws from interacting with Nate, leaving him in the throes of conflict with an abusive father, a nervous mother and barely-there older sister. Just when things couldn’t get any weirder for Nate, his father loses his insurance job and begins working at a funeral home owned by Andrew’s father. For the next couple of years Nate and his father feud and fight in a series of two or three punch fights, including a grotesque display of callous behavior on both father and son during a family visit to Aunt Rebecca’s house. After mouthing off about keeping Nate’s mom out of the financial picture should she ask for a divorce, Nate begins to cry and retreats to the car outside where he fumbles for a cigarette. When his father goes to check on him, Nate loses it. “How could you say that about Mom you piece of shit!” Nate shouts with tears before pulling his father out of the car, throwing him into the snow and kicking him in the stomach.

Within a year of the incident, Nate’s fears come to fruition and his parent’s divorce. Nate spends years couch-surfing, pill-popping, a drug overdose, all the while trying his best to get back into University. The vitriolic charges portrayed in letters and voice messages sent to family members demonstrates the drama going on in the protagonists head and also draws on an element of wrestling subculture: the shoot interview style, which of course I put together when later in the book we discover that Nate’s knowledge of wrestling as a teen leads to a part-time job at a media website. A wrestling shoot interview is a popular form of video interviews ex-wrestlers does to tell their side of an infamous wrestling storyline or backstage drama. There are literally hundreds of them on Youtube. The later half of the book acts as a rerun of Nate’s unraveling, reliving the pain of growing up, the rejection of his parents and his years “pilled out of my mind”.

The prose are at times detached, poetic and marred by emotional analysis. Footnotes add to the tell-all feel the novel oozes with, and accompanying artwork by Andrea Bennett and Vicki Nerino give the book a sickly sweet aesthetic.

With its multiplicity of domestic settings and kaleidoscopic mix of wrestlers, Christians, truth, evil, George Michael, masturbation, sibling rivalry, the mental health system in Canada, New Order, eventual redemption, Savage 1986-2011 is a memorable memoir packaged as a novel, not to be read by candle light too close to your own family’s powder keg of secrets.

***

Jenny Simpson is a poet and visual artist living in Edmonton, Canada.

February 24th, 2014 / 11:00 am