Detachment: On Shira Dentz’ door of thin skins

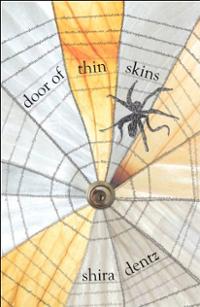

door of thin skins

door of thin skins

by Shira Dentz

CananKerry Press, 2013

96 pages / $16 Buy from Amazon

The retina is brain tissue that lines the inner surface of the eye, captures images of the visual world, and communicates them to the brain. Retinal detachment is a disorder in which the retina peels away from the eye. It is often caused by an injury or trauma to the eye or head that breaches the barrier. That breach that allows fluid to seep under the retina and to peel off the way wallpaper peels from a wall. Initially, the person might initially see clouds in their vision often called “floaters.” As detachment progresses, a moon-shaped shadow appears in the periphery of the visual field and starts to billow like a sail in the wind.

Shira Dentz’s door of thin skins narrates a fairy-tale-like story, “perhaps / a fairy tale,” of a young woman’s trials with her shapeshifting psychotherapist, Dr. Abe. Part lizard, part whale, part Macy’s Day balloon, Dr. Abe is a big man with narrow tongue, “but really it was such a narrow tongue.” Dr. Abe’s office is a veritable forest with its brambly hedges, placid buffalos, quick meadows, and spider plants. It is “fashioned according to Freud, lover of the primitive.” Trained at the White Institute along with Rollo May and under the tutelage of Eric Fromm, Dr. Abe also fashions his practice after one of the institute’s major influences, Sandór Ferenczi, the Hungarian psychoanalyst and contemporary of Freud.

Both Sandor Ferenczi and Otto Rank broke from Freud in the 1920’s to collaborate on the development of a different form of psychotherapy. Claiming that Freud’s requirement for emotional detachment on the part of the psychotherapist leads to “an unnatural elimination of all human factors in the analysis,” they endorsed a type of “here-and-now” approach that emphasized the clinical importance of attachment, intimacy, and intersubjectivity, encouraging more countertransference and mutuality between patient and doctor.

Ferenczi is also widely known for his “confusion of tongues” theory of trauma. In his essay on the topic, he explains that when children playfully communicate the desire to be the spouse of a parent, they are speaking with a infantile and tender tongue. “We find the hidden play of taking the place of the parent of the same sex in order to be married to the other parent, but it must be stressed that this is merely phantasy; in reality the children would not want to, in fact they cannot do without tenderness…” According to Ferenczi, the danger lies when the pathological adult misinterprets this call for tenderness as a call for passion.

In fact, in the 1920s, Freud broke from himself and repudiated his theory that female hysterics really suffered sexual abuse. According to Judith Herman, he did this because he could not cope with the truth that sexual abuse was pandemic and therefore repressed it. In my thinking, the same sort of repression may have occurred with Ferenczi in his “confusion of tongues theory,” for according to him, the confusion is still based on mutual dialogue, on the innocent participation on behalf of the child. Perhaps like Freud he couldn’t cope with the fact that many children do not participate in the conversation. They don’t call out for tenderness in some sort of spousal fantasy. Instead they cry angrily for safety while the “pathological” adult ignores these calls and forces the “pathological” tongue upon the child. Certainly this is true of Dentz’s child.

Here, Dentz speaks to the event in the third person. When she screams, when she articulates her infantile and angry tongue. Her voice is detached from first-person self, for the “I,” could no longer bear witness to real world but instead is left floating in a world of chaos.

July 26th, 2013 / 11:00 am