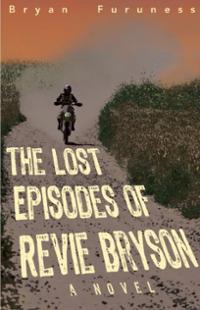

The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson

The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson

The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson

by Bryan Furuness

Black Lawrence Press, March 2013

309 pages / $18 Buy from SPD or Black Lawrence Press

Bryan Furuness’s first novel, just out from Black Lawrence Press, takes on taboo territory – both the taboos of polite society (parental separation, suicide, rape, incest, abortion), and the taboos of impolite contemporary fiction (namely, Jesus). By which I mean Jesus as a good guy, Jesus as possibly ourlordandsavior. The volatile tension that results when you mix the unspeakable with the overspoken complicates what could otherwise be a well-written but conventional coming-of-age novel. Its subtle moralizing threatens didacticism but is consistently surprising and complex enough that it will at least goad readers into remembering how daunting it was as child to observe so much of the adult world invested in the Bible – a kid’s story of good and evil, impetuous gods and walking dead.

I was first introduced to Furuness – and to Revie Bryson – in a story called “Ballgrabber” that appeared in Hobart 9. Revie surveyed the world of kids in such an irreverent, fresh, hilarious way that I filed Furuness’s name away and vowed to read his first novel whenever it came out. I read Lost Episodes in three days, and that same irreverent freshness was there to remind me why I’d been anxiously awaiting its release.

The book opens with Revie believing that, on his twelfth birthday, God will reveal that he is, in fact, the second coming of Christ. As Revie begs his father to take off work and be there for the big event, Furuness riffs on a quote from the Gospels that lingers somewhere in many of our minds: “I needed him there when the big voice came from the sky, declaring me His son, with whom he is really excited to be working” (24). Revie’s mother, whose Hollywood dreams were dashed by early motherhood, departs early in the novel for a last-ditch pilgrimage to La-La Land, leaving Revie and his father back in Indiana, feeling – I love this – “awful and tender” (107). The family’s brokenness brings out the worst in everyone: Mom’s pathetic optimism, Dad’s inability to handle the most meager domestic duties, and Revie’s devastating speculations, such as: “Our family was the toxin my parents were trying to flush from their systems” (130).

As with any novel that takes risks, this book is vulnerable to some heavy questions. Why do our estranged parents finally have makeup sex right after discussing their son’s sexual activity? Are they getting off on it? Why do Revie’s clothes need to come off as a peripheral character steps up to deliver the novel’s main moral crux? Part of me wants to tap the side of my nose and suggest we should give kid nudity and catechism class a bit of distance, but a greater part of me applauds this book’s exploration of daunting life circumstances we normally hide behind euphemisms like “messy terrain.” I’d rather a novel raise problematic questions than just answer comfortable ones.

April 29th, 2013 / 11:00 am