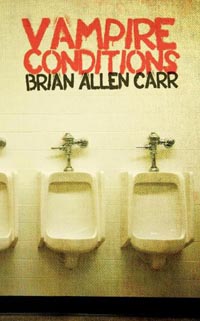

Vampire Conditions

Vampire Conditions

Vampire Conditions

by Brian Allen Carr

Holler Presents, 2012

114 Pages / $9.99 Buy from Amazon or Powells

When given the choice, I mostly choose not to read literary realist fiction. I’ve been out of school for more than a year now, so I’m accustomed to having the choice. I read Brian Allen Carr’s collection Vampire Conditions anyway, and I loved it. I knew that I wanted to review the book, too, which meant that I would have to find a way to articulate why I loved it. There are two keys. First, Carr takes nothing for granted. Second, he never justifies his stories.

Carr’s refusal to take anything for granted makes him different from most writers of literary realist fiction because most of these other writers — the ones I now choose not to read — will resort to writing what they think “it’s really like” when they aren’t sure what to do next. That is to say that they often make boring events and characters (affairs and the middle-aged people who have them, unconsummated affairs and the middle-aged people who don’t have them, cancer deaths and the survivors who mourn them, suicides and the people who commit them, drugs and the people who use them) and congratulate themselves for writing the world the way it is. This takes the reader for granted because it assumes his or her interest will sustain itself without the writer’s help. This takes the world for granted because it suggests that the way we expect things to be is the way they are. Such writing fails as an imitation of reality; nothing in this life is ever much like what it’s “really like.”

I don’t believe that Brian Allen Carr writes his literary realist stories by asking himself what is likely or real. If he were doing it that way, he wouldn’t have made up Thick Bob, a grotesque who one day gave a bartender so much shit she actually tased him — and who, when he saw how much pleasure it brought the bar’s other patrons to see him tased and collapsed on the floor, proceeded not only to continue antagonizing the bartender, so that she would regularly repeat that performance, but to mount brief shows on a small stage inside the bar, wherein said bartender hits him with a bat, explodes fireworks in his clothes, throws darts at his person, and etc. If Brian Allen Carr wrote stories by asking himself what is likely, he wouldn’t have invented the protagonist of “Lucy Standing Naked,” a young boy of Asian descent, adopted by white Texans, who is named Nelson, and who is learning to play the guitar, and who sings country music better than most white boys, and who is in any case a novelty because there’s never been a famous country singer who looked like him. He wrote Nelson because Nelson was interesting. He wrote Nelson because Nelson makes a good yarn.

January 4th, 2013 / 12:00 pm