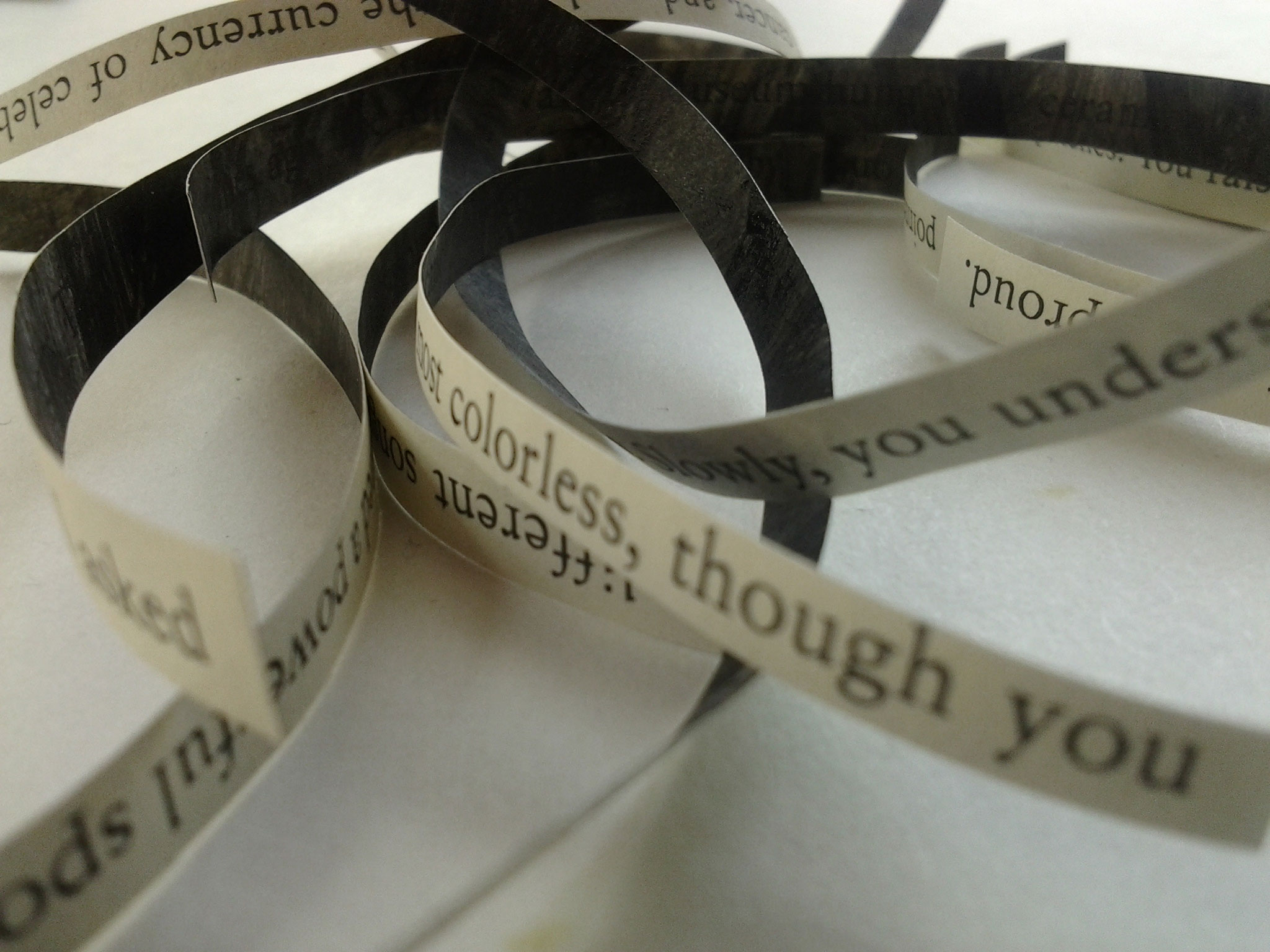

Another way to generate text #7: Gysin & Burroughs vs. Tristan Tzara

A while back, I ran a little series, “Another way to generate text.” The first one proved fairly popular, and I’ve been meaning to make more of them, but generative techniques haven’t been on my mind. However, my post last week, “Experimental fiction as principle and as genre,” generated a lot of text (haha), in the form of comments. Some people who chimed in questioned whether the Cut-Up Technique that Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs developed and used in the 1950s was ever all that experimental. Specifically, PedestrianX wrote:

I find it hard to accept this argument when its main example, the Cut-up, didn’t start when you’re claiming it did. I’m sure you know Tzara was doing it in the 20s, and Burroughs himself has pointed to predecessors like “The Waste Land.” Eliot may not have been literally cutting and pasting, but Tzara was.

This comment got me thinking about the role influence plays in experimentation; more about that next week. Today I want to address the point PedestrianX is making, as it strikes me as pretty interesting. Were Gysin and Burroughs merely repeating Tzara? Or were they doing something substantially different?

To figure that out, I decided to run through the respective techniques, documenting what happened along the way. Because if I’ve learned anything in my studies of experimental art, it’s that thinking about the techniques is usually no substitute for sitting down and getting one’s hands dirty.

If you want to get dirty, too, then kindly join me after the jump . . .

Experimental fiction as genre and as principle

A few years ago at Big Other I wrote a post entitled “Experimental Art as Genre and as Principle.” That distinction has been on my mind as of late, so I thought I’d revisit the argument. My basic argument then and now was that I see two different ways in which experimental art is commonly defined.

By principle I mean that the artist is committed to making art that’s different from what other artists are making—so much so that others often don’t even believe that it is art. As contemporary examples I’m fond of citing Tao Lin and Kenneth Goldsmith because I still hear people complaining that those two men aren’t real artists—that they’re somehow pulling a fast one on all their fans. (Someday I’ll explore this idea. How exactly does one perform a con via art? Perhaps it really is possible. Until then, I’ll propose that one indication of experimental art is that others disregard it as a hoax.) Tao visited my school one month ago, and after his presentation some folks there expressed concern, their brows deeply furrowed, that he was a Legitimate Artist—so this does still happen. (For evidence of Goldsmith’s supposed fakery, keep reading.)

Eventually, I bet, the doubts regarding Lin and Goldsmith will fall by the wayside. Things change. And it’s precisely because things change that the principle of experimentation must keep moving. The avant-garde, if there is one, must stay avant.

That’s only one way of looking at it, however. Experimental art becomes genre when particular experimental techniques become canonical and widely disseminated and practiced. The experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, during the 1960s, affixed blades of grass and moth wings to film emulsion, and scratched the emulsion, and painted on it, then printed and projected the results. Here is one example and here is another example. And here is a third; his films are beautiful and I love them. (The image atop left hails from Mothlight.) Today, countless film students also love Brakhage’s work, and use the methods he popularized to make projects that they send off to experimental film festivals. (Or at least they did this during the 90s, when I attended such festivals; I may be out of touch.)

Those films, I’d argue, while potentially beautiful and interesting, are not necessarily experimental films. As far as the principle of experimentation goes, those students had might as well be imitating Hitchcock.

Nothing is True, Everything is Permitted

But these operations do not occur in neutral territory, Kaye was quick to point out. Burroughs treats all conditions of existence as results of cosmic conflicts between competing intelligence agencies. In making themselves real, entities (must) also manufacture realities for themselves: realities whose potency often depends upon the stupefaction, subjugation and enslavement of populations, and whose existence is in conflict with other ‘reality programs’. Burroughs’s fiction deliberately renounces the status of plausible representation in order to operate directly upon this plane of magical war. Where realism merely reproduces the currently dominant reality program from inside, never identifying the existence of the program as such, Burroughs seeks to get outside the control codes in order to dismantle and rearrange them. Every act of writing is a sorcerous operation, a partisan action in a war where multitudes of factual events are guided by the powers of illusion … (WV 253-4). Even representative realism participates – albeit unknowingly – in magical war, collaborating with the dominant control system by implicitly endorsing its claim to be the only possible reality.

From the controllers’ point of view, Kaye said, ‘it is of course imperative that Burroughs is thought of as merely a writer of fiction. That’s why they have gone to such lengths to sideline him into a ghetto of literary experimentation.’

If love can be a brainworm then I would like to talk about my brainworms

I met someone who gave me brainworm recently. I used to think of brainworm as something that I would own and hold. I thought, “The person who gives me brainworm will be mine and I will be theirs.” The new brainworm I found does not feel like something I need to own or hold. It is a thought that continues to eat wherever it wants to eat. I enjoy the feeding of this thought. The feeding is endless. I could let this feeding continue the rest of my life and I would be happy even if I never saw the person who gave me the brainworm. I am so full of brainworm that I am sick. It seems stupid that I could be so happy about having something as dumb as a brainworm.

I met someone who gave me brainworm recently. I used to think of brainworm as something that I would own and hold. I thought, “The person who gives me brainworm will be mine and I will be theirs.” The new brainworm I found does not feel like something I need to own or hold. It is a thought that continues to eat wherever it wants to eat. I enjoy the feeding of this thought. The feeding is endless. I could let this feeding continue the rest of my life and I would be happy even if I never saw the person who gave me the brainworm. I am so full of brainworm that I am sick. It seems stupid that I could be so happy about having something as dumb as a brainworm.

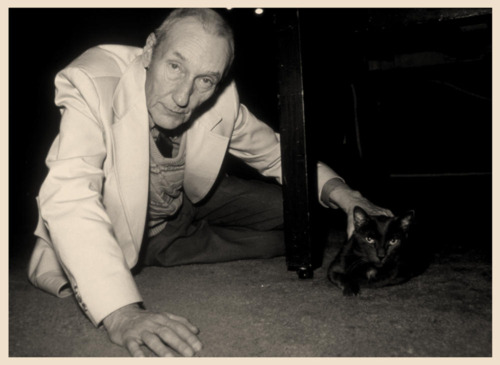

Tonight I ate some cheese. I was one of the last people in a room eating cheese. An elderly woman who reminded me of my grandmother began talking. She talked about the time she saw William S. Burroughs read. She went to the reading because she wanted to ask him a question. A lot of people at the reading just wanted to take William S. Burroughs out and get him drunk to see what would happen. She never asked the question she wanted to ask because she didn’t know how to formulate it. I continued to eat cheese and listen. The elderly woman said, “If I had a chance to ask William S. Burroughs a question now I would ask him: but what about love?”

My roommate just got home. He said, “Hellllwwwwwooooo” when he walked in the door. He likes to pretend he is a cat and an Asian when he says “Hello”. When he said, “Hellllwwwwwooooo” just now he was actually saying “Hello” to all the haters who will say they don’t believe in brainworm and think its so heterosexual to believe in something like brainworm.

But yes, I have a brainworm that I’m prepared to live with for the rest of my life and not doing anything about.

Ignorant Proclamation +2

1. At The Observer, another stockbroker says another dumb thing about the state of fiction.

Dear Lee: When your weathervane is James Wood, you might as well be covering the World Cup. Where have all the Mailers gone? I only ever knew of one, and he’s dead. Try actually investigating something. Open your eyes.

2. At the Guardian, Jeremy Kay reports from the set of the new Herzog/Lynch collaboration.

3. At Pop Damage, an interview with James Grauerholz, the executor of the William S. Burroughs estate.