How I wrote my latest novel, part 2

Last week, I documented how I came up with the initial idea for my latest novel—“Lisa & Charlie & Mark & Suzi & Monica & Tyrell,” which I was then calling “The Porn Novel”—and how I simultaneously began exploring that idea and laying out some basic formal parameters. I also provided a general overview of my general writing process. Today I’ll cover how I finished this initial exploratory period and settled into a stronger sense of the project as whole. Again, my hope is that these posts will prove useful to other writers, and interesting to everyone on God’s green earth. Because I remember very clearly that, during the decade I spent writing my first novel, Giant Slugs, I often felt frustrated and confused. And while every writer must figure ultimately things out for her or himself, some of my strategies and methods might prove theft-worthy—or at least provide a good laugh.

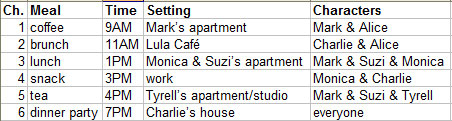

So I’d gotten to the point where I’d translated the original idea (“a pornographic novel that doesn’t contain any sex”) into a more specific approach: six chapters featuring six friends meeting up for six meals. I knew that each chapter was going to be long, to make the absence of salacious material more palpable. And I’d whipped up some character names, and sketched out a list of potential meals.

I also tried estimating how long each chapter would have to be. I decided that, in order to convey the proper feel, the first five chapters should be at least 20 pages each, and that the final chapter (the group dinner) should be longer—at least 30 pages. That added up to 130 pages minimum, which felt like the shortest the project could be. I translated that into word counts, since I think better that way (for one thing, I always single-space my manuscripts, since years of teaching/grading, not to mention taking writing workshops, have led me to despise the look of double-spaced manuscripts). I had a sense that the project would be dialogue-heavy and not contain any long paragraphs, running maybe 250 words/page. Hence, the projected numbers worked out to 5000+ words apiece for chapters 1–5, and 7500+ words for chapter 6. These were just targets, of course, but having a rough idea of what I’m aiming at helps me pace myself, and estimate how long the writing will take.

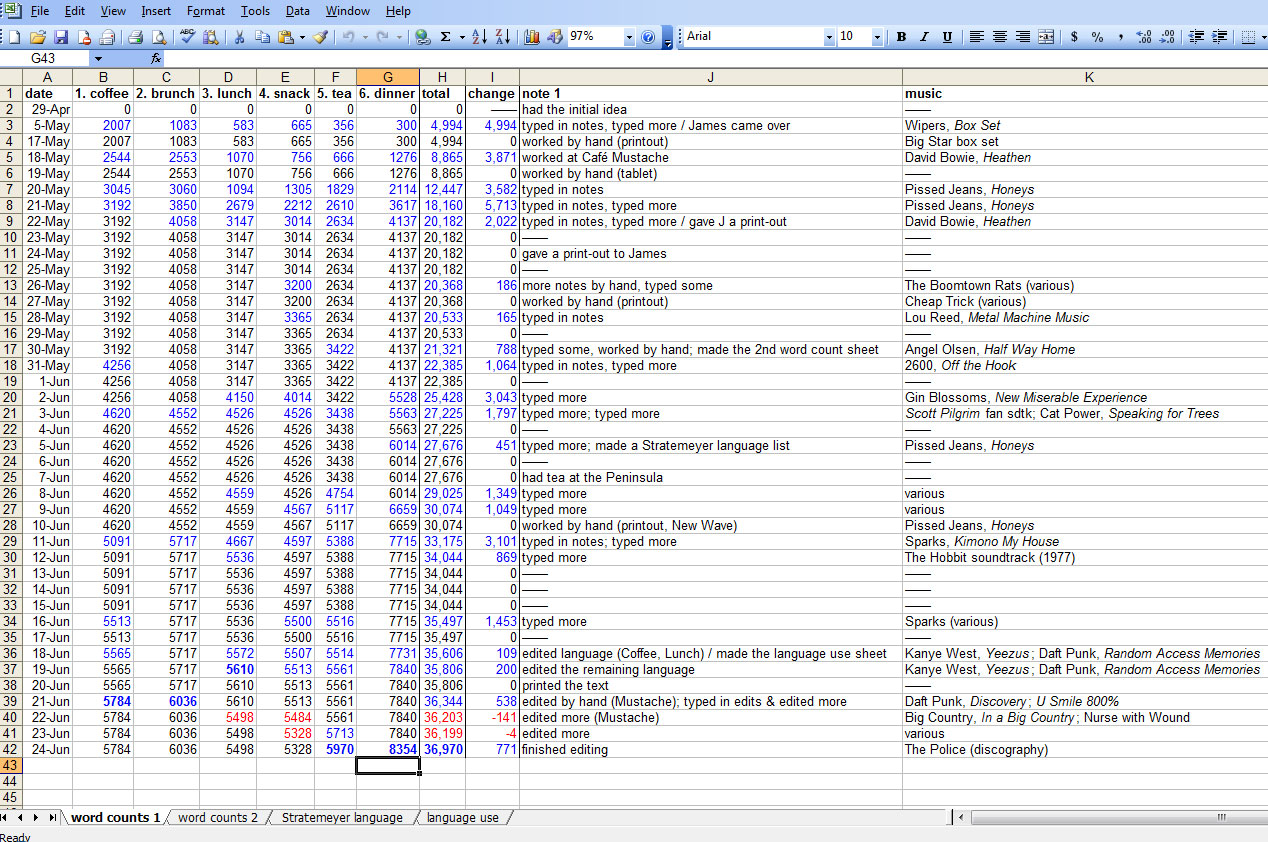

I also started my writing journal. I use Excel for this and it’s nothing extravagant; I just note each time that I work, and jot down a few words as to what I did. I also track the word counts as they change (using blue for increases and red for decreases). And while this habit of mine is probably the sign of a diseased mind, it helps keep me motivated, encouraging me to “log in” every day, and stick to my routine. It’s not unlike tracking my workout routines, or the movies that I watch. Plus it yields data I can later analyze, which is the only thing that sustains me through the long cold Chicago winter. (Dear NSA, I hear you had an opening recently? Call me!)

Now before you think me entirely insane, consider this. I have a simple litmus test for what enters/exits my writing routine: is it fun? I write a lot, and want to enjoy it, and make it something I look forward to doing. As such, I’m always looking for little ways to reward myself, and to make the situation more pleasant / less stressful.

For example: when I was younger and writing only fitfully, I mostly wrote late at night, even though I never had much success doing that. Writing was something I did after stressing out about it all day, feeling guilty about not having gotten any work done. After a decade or more of that, I switched to writing in the morning—and, believe me, I did not think I was a morning person at that time. But I started living with a yoga instructor who taught early morning classes. So I started getting up at 5 AM and, amazingly, I discovered that I was much more productive and happier when I wrote then. (I also realized that predawn is my favorite time of day.) That experience taught me to examine the rest of my writing routine, and to try making it more enjoyable overall. So my Excel files are in some sense silly, yes—but they are my only friends, and I name them, and I love them.

Here’s a snapshot of the journal that I made:

(That’s the finished version. I fill it out line by line, day by day.)

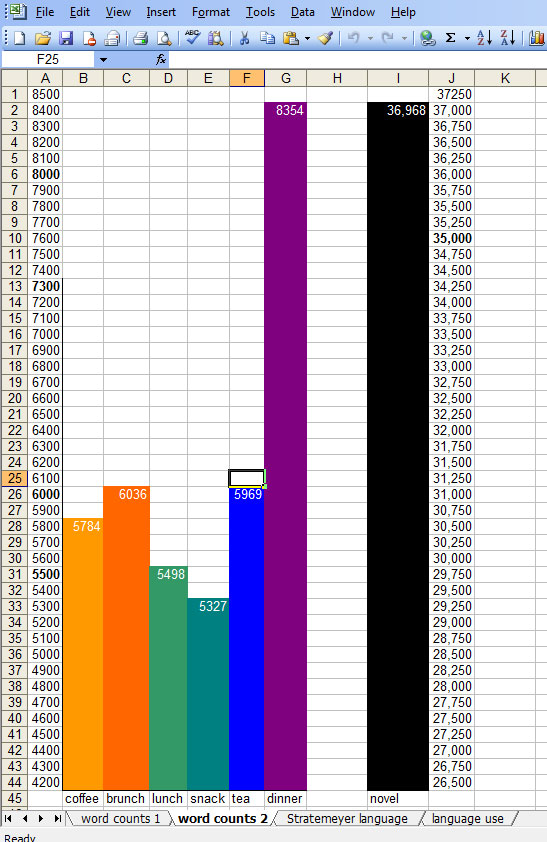

I also made a second spreadsheet, where I could visually track the word counts of each chapter as they developed. This provides further motivation—I find that one of the more challenging aspects of writing a novel is the absence of the immediate gratification provided by stories and poems (and blog posts). You have to keep plugging away and believing you’re making progress. Watching the columns creep upward helps me feel like I’m getting there:

All right, now you may think me thoroughly insane.

I’m not saying that making colorful Excel sheets like this is for everyone. And I might finish novels faster if I skipped making them myself. But have you also considered that humans invented writing in order to give them an excuse to make colorful Excel sheets?

Back to the literary form that was gradually emerging. All this time, I kept bashing out text, freely exploring ways that the conversations could go. As I did that, I tried imagining or distilling larger principles that could guide and structure the work. Again, I went with what felt good, though I also asked myself why I thought it felt good.

For instance, the more I worked, the more I began thinking about the novel’s style. I wasn’t revising or editing the prose yet—far from it!—but I was looking at the words that I was producing, and wondering which way they might eventually go. And I started thinking that I didn’t want the language in the novel to be particularly clever or acrobatic. That is to say, I wanted the finished language to be on the simpler, plainer side, neither intricate nor ornate.

I should stress that this is a real departure my other novels. Giant Slugs consists of nothing but clever sentences:

We’ll all follow the finer taboos, the tattoos of a pro percussionist’s tom-toms. I’ll recall the tablets my kiddy fingers traced, guided by my father’s gauzy own, which when young gripped the blunt reed and delicately dedicated his bird-like words to clay.

“We’ll all follow” = “We’ll all fall” (extensive Humpty Dumpty imagery runs throughout the book). And “pro percussionist’s tom-toms” = “proper customs”—in writing Giant Slugs, I did scads of “word splitting,” a technique I described more thoroughly in this post. That book required that I spend long hours revising the language, packing in as much wordplay as I could. And while my second novel, “The New Boyfriend,” is far less punning, its first-person narrator is still a clever person (a “wordy“), who relates events in a wryly circular style:

I tried to deny it, but there was simply no use in denying it: the two of them made a very cute couple.

“You make a cute couple,” I said at last. “There’s simply no use in denying it!”

“Still,” Lauren exclaimed, “I can imagine you denying it!”

“No, not true, not true!” I cried, very playfully. “I wouldn’t ever!”

“You’re such a denier,” Lauren said; she said this mainly for the benefit of the new boyfriend. There was no use in telling Melanie—she already knew this (and much more) about me. “Just begging to differ—such a contrarian, very contrary.”

Well, I could see that there would be no use in my denying that.

In the case of this new novel, I wanted to try something less self-conscious. The writing would still be stylized (all writing is), but I decided to make it as invisible as possible. The way I articulated it was that the story’s third-person narrator should have no psychology whatsoever. (Mind you, I don’t think that’s really possible, but I tried to approach that concept the way a parabola approaches its asymptote.)

This decision felt right to me for various reasons. Pornographic films employ small talk and flimsy plots as a means of getting to the “real” content: the pizza guy shows up at the sorority house, and there’s some dialogue about how big a tip he should get—but that’s just an excuse to justify the sex, and no real effort is spent on it. It just has to be “good enough.” In the case of this novel, I wanted nothing but the pretext.

At the same time, however, I knew that I didn’t want to use any double entendre, even though that’s a staple of pornography. But I wanted the finished book to be innocuous—totally stripped of any titillating content. Double entendre functions metaphorically: the literal content stands in for some other meaning. I wanted only literal meaning, and no direct allusions to sex. (It helped me to think that sex might not even exist in the fictional world I was describing.)

Writing very plainly helped make the novel feel more perverse to me (and, despite the dearth of titillation, I wanted the prose to achieve a perverse quality—I just didn’t want to do so by including or alluding to sexual content). And here the novel’s form was influenced by the literary culture at large. Because I’ve felt for a while now that, in general, the literary writing scene overvalues clever and ornate language, valorizing it at the expense of other formal issues in writing (see, for instance, my critical post “The Barthelme Problem,” which I think I should try revisiting). I don’t think that literary excellence hinges on clever writing. This new project, then, offered a chance to try making something literary and enjoyable without employing dynamic sentences or an overly flashy style. (I’ll say more about the style that did develop in part 3 or 4.)

All this time, I kept thinking about the characters and the meals they would be sharing. I knew I wanted three women and three men, and had assigned them names (which never changed). Since a lot of the rest of the novel was shaping up to be pretty homogeneous in both style and form—meal after meal after meal, rendered in a pretty straightforward fashion—I decided to introduce variety at the level of character, setting, and event. I started brainstorming scenarios that I wanted to include: a scene in a restaurant, a scene in a workplace, a scene in a garden. The characters also started coming into focus: Monica was a tall elegant European woman, slightly fussy and bossy. Charlie was a somewhat heavyset older man, and something of a glutton and a lecher. Mark was a goofy hipster writer. Suzi was a spunky Asian-American photographer, unselfconscious and uninhibited.

I should emphasize that all of these thoughts were happening simultaneously and influencing one another. Knowing that I wanted the style to be on the plainer side affected the way the characters would speak, which in turn affected their personalities, and vice-versa.

Looking back now, the characters and the finished chapter/meal structure strike me as obvious, but it took me a while to figure it out. My 6/6/6 structure, for instance, didn’t seem viable given my desire to have one character appear in chapters 1, 2, and 6. (See part 1 for more on the reasoning behind both of those decisions.) The problem here was twofold:

1. It looked as though one character would have to appear in too many chapters, and I wanted the novel to be about the group, not a single character. So I didn’t want anyone to show up more than three times.

2. It seemed unrealistic that the characters would eat so much in a single day, and I wanted things to be generally plausible.

Whenever I run into formal problems like this, my preference is to tackle them head-on, because ignoring them only creates bigger problems later. Also, solving problems early on helps me clarify what’s important. My method is simple: I ask, “What should my priority be?” or, “What do I most want to do?” Answering that tells me what’s negotiable and what isn’t. (This is one way that I’ve applied to my writing the Russian Formalists’ notion of “the dominant”).

Seeing as how I’d reached a make-or-break point, I set aside a morning to hammer things out. I went to one of my favorite local cafés, taking along some of my favorite materials: cheap blue Bic pens and a yellow legal tablet, plus David Bowie’s brilliant album Heathen, which Shaun Gannon turned me on to (thanks, Shaun!). Settling in with a bottomless cup of coffee, I proceeded to make a list of the things I knew I wanted:

- for there to be 6 character / 6 meals / 6 chapters;

- for the novel to take place over the course of a single day;

- for each character to appear in 2–3 chapters—no more, no less;

- for one character to appear in chapters 1, 2, and 6;

- for two chapters to feature three characters (male-male-female and female-female-male);

- for the final chapter to include everyone;

- for the whole thing to read plausibility (I realized that I was writing realist fiction, which was a first for me—all of my other fiction is fantasy).

But whatever combinations of characters and meals that I tried, I kept running into problems. One character, it seemed, would have to repeat too many times. And I still couldn’t figure out why they were they eating so damn much! I considered removing one or more of these criteria: having the novel take place over a few days, or adding one or more characters. But those solutions felt wrong.

So I kept hammering away. In the end, two things helped me solve this problem (or interconnected set of problems):

1. I remembered that I wanted to feature variety at the meal level. The six meals didn’t have to be equal in size or importance. Making three of them smaller accomplished a great deal. I revised my list of meals and decided upon coffee, brunch, lunch, a snack, tea, and the concluding dinner party.

2. I also employed a trick I learned while writing Giant Slugs: write the problem directly into the work itself. Why would some of the characters meet for tea if they were going to a dinner party in just a few more hours? Well, what if they themselves addressed that very issue? I immediately sketched out some dialogue in which one of the characters apologized for the tea being simple and light, since they would soon be heading to the dinner party. So why then were they meeting for tea? Well, they’d been talking about doing so for months. One of the characters had never had a proper British tea before, and was desperate to try it. But why would they meet up on that particular day? Well, the fellow in question would soon be leaving the country, and this was the only day that all of them were free. So they were doing it to say that they had done it.

One of the characters, Tyrell, thus became British. He was also a painter, and Suzi had been modeling for him as of late. The two of them had shared tea many times before. Mark and Suzi were leaving soon for Thailand, and Mark was the tea virgin. Suzi and Tyrell were eager that Mark should join them for tea at least once before the trip.

I also decided that the party in the final chapter should be a surprise birthday party. That way, at least one of the characters (Charlie, who became the birthday boy) didn’t know it would be happening, which made it more plausible that he’d eat a lot at brunch. (I also made him something of a glutton, with a tendency to announce that he shouldn’t eat something right before doing so.) Charlie, meanwhile, was planning his own surprise party for Mark and Suzi …

Now I had a good sense of what I wanted to accomplish, how long the novel would be, and how I was going to structure it:

With this now resolved, I could focus more on the conversations that the characters were having, as well as building suspense and intrigue into the novel. … More about which in part 3!

Tags: Excel, Giant Slugs, novel writing, pornography, Roman Jakobson, Russian Formalism, The Dominant, Viktor Shklovsky

Mark seems to be an exception with his four meals. Diagetically makes sense since two of the meals are coffee and tea, but breaks the “no more, no less” rule.

Ah, yes, I should have mentioned that. Something had to give, so Mark ended up sneaking his way into four chapters. I compensated by making him more passive. He mostly hangs back and chills, going with the flow, while Monica and Charlie are more aggressive and drive things.

It also helped, I think, that Mark showed up in 1, 3, 5, 6. Not being in 2 and 4 made it feel more like he was popping in and out, and wasn’t a focus of attention? At least, that was my reasoning…

Interesting!

Yr excel stuff sounds similar to the Seinfeld method. The one where you draw a big red X in yr calendar every day you work, & after a while the Xes start to accumulate, which puts a psychological pressure on you to work and scratch that beautiful red X in. Don’t break the chain!

Also, no homosexxxual chapters? At least a lesbian scene is a mainstream porn convention.

Definitely similar to the Seinfeld method! Funny, last year I watched the box set, and saw some writer interviews where they talked about that.

Half of the chapters (3, 5, 6) feature same-sex pairings, and I varied them by making them MFF, MMF, then group (which starts with everyone, then turns into constantly changing couples and trios). Also, in the MMF chapter, the woman (Suzi) leaves early, so it becomes MM until the end.

More please. These are great. (Also really enjoyed The Barthelme Problem article). Thank you.

Thanks!

So the entire, completed novel is 37,000 words long?

Yes—36,968, actually. 150 MS pages.

Nice. This is the stuff I like–your spreadsheets, and the dissection of sentences from your previous novels; the discussion on why you made the choices you made, etc. I cannot wait for the “dialogue” portion of this essay. How the novel actually reads/feels/sounds. Good build-up. Part 3, now; please!

So it’s really a novella.

If you say so. I don’t think there are any official rules regarding what is a novel and what isn’t. Nor do I think it’s really all that important?

You don’t know the rules?

0-15k short story

16-30k Kindle Single

30k-80k novella

regular novel

maxi-novel “Middlemarch””Infinite Jest” etc.

Those aren’t “rules,” and there’s no consensus to how long novels are or should be. That’s because “novel” isn’t any kind of official term backed by any kind of authority. It just basically means “a long work of fiction, distinct from a story,” and different people have different ideas as to how long “long” means—but it’s not like measuring the speed of light, or determining whether a cheese is truly Camembert.

When I was in college, a writing professor told me that anything longer than 45,000 words was a novel. Nanorimo says 50,000 words. You say 80,000 words. Meanwhile, plenty of works much shorter than all of those limits are commonly labeled and considered novels. Have you read for instance The Malady of Death? It’s 60 pages long, if that, and it says “A NOVEL” right there on the cover in fancy script.

If you think a novel has to be at least 80,000 words long, then by your criteria, I’ve not written a novel. I myself don’t define a novel that way, and feel perfectly comfortable calling this new work a novel. Feel free to not call it one yourself, because I honestly don’t consider it all that important a distinction. I mean, what’s really at stake, beyond perhaps marketing issues?

The way I tend to look at it, there are novels and there are stories. Stories can be read in one sitting and usually don’t have any interruptions (like chapter breaks). Novels are longer and often broken up, to make them easier to put down and pick back up. Beyond that, I don’t sweat the difference. This new MS is six chapters long and I doubt anyone will ever read it straight through, so a novel it is.

Cheers,

Adam

Thanks! And Part 3 next week!

Another point perhaps worth considering: the trend in contemporary publishing seems to me toward shorter and shorter work. How many magazines now print stories upwards of 15,000 words? I recently submitted an 8000 word story to a journal and the editor just laughed at me, said they no longer publish anything over 3000 words.

I took a novel workshop last year, and the prof warned everyone in it that any MS longer than 200 pages would be difficult to publish. She encouraged us to aim for writing 150–200 page novels.

These things are all trends and they’re always in flux. I think the novel/novella distinction mattered more in a different time and place.

I was just playing. You referenced marketing being against the “novella” so I’m surprised your teacher told you the trend is towards shorter books. Personally, I like novels to be at least 220pp if I’m paying ~$14 or else I feel dumb. But actually I never care about labels or length if I’m not paying for it.

I think it’s noteworthy for a couple of reasons. The first is that I recognize a trend here. It seems to me that many people within this subculture prefer to turn out material quickly as opposed to producing work of lasting and interesting value. Writing a book seems to be the point, as opposed to writing a *good* book. The authors whose work I most admire did not (and do not) churn out 40,000 word “novels” in a month.

Writers of pulp–of which, I’ll admit, there have been several true talents–churn out quick, formulaic novels. But writers of very good work often spend years (and at the very least many months) writing their books. They do not treat the process as a race to produce material so that they can can get their names into the world.

Shane Jones had a post on the 30th of last month about publishing in print journals, and how he was surprised to learn that people in the actual publishing industry still find such publications to be of value. He estimated that the amount of time required for him to draft, edit, and submit a story was ten hours. In my opinion, that’s an absurdly short time to spend on a story. It seems a given that a story that only took ten hours of one’s life wouldn’t end up in any respectable magazine, even though one could always find a website (possibly run by an acquaintance or friend) on which to post said story.

The second reason I think the question of your book’s length is interesting is that, if it really didn’t matter, you would just call the book what it is, which is a novella, not a novel. There’s a sort of self-aggrandizement at work in these posts about the speed with which you wrote a novel.

It would be the same if you had recorded three five-minute songs and then went on at length congratulating yourself for recording an album and showing everyone how it was done. Sure, if you look you can find other records with only three songs that have written on their covers “an album,” but everyone knows it’s just three songs. And three songs does not an album make.

The Malady of Death is less than 5,000 words. The cover can say what it likes, but 5,000 words is not a novel.

In my experience the most profitable way to judge if something is any good is to read it. So I really don’t care if it took Shane Jones 10 hours to write a story or 2 years, if I think it’s good. I also generally don’t care if a book is 40,000 words and calls itself a novel. Mostly I just care if it’s good.

Now, that’s in my experience. And I understand that what you’re saying is that you see a correlation between things that did not take that long to write or are not very many words and things that are not to your taste/in your opinion good. I wouldn’t presume to tell you what to like or not like. Just offering a counterpoint of sorts.

Oops I posted that and I had other thoughts:

Poetry is, to a limited extent, different, but I will say that some of the poems I’ve published in places I really respect/hold in high esteem and that I think other people respect/hold in high esteem have taken me a very short amount of time to actually write. I will namedrop places if you need me to, just trying to mitigate the self-aggrandizement aspect you’re talking about (which maybe, or probably, does really exist in some people). One poem that I think was reasonably strong took me only 30 minutes or less to draft. Then I sat on it or sort of held it in the back of my mind for 3-4 months, edited it for another 30 minutes or less, sent it out, and got it placed in a cool journal. Did that poem take me an hour to write, or 3-4 months? Is it automatically shitty because I only spent an hour of actual writing time on it? Real questions, not rhetorical.

Then again, I try not to run around telling everyone “yo, check out this poem I just published, I wrote it in 5 minutes!” at least

Hey Trey, I totally agree. Poetry is a bit different. But even treating it as the same, I think it’s perfectly natural and right that there are instances in which a piece of art comes to its author as though it existed within her or him fully-formed. As a result, a poem written in an hour might be the most powerful piece in a collection or even a body of work. But in that instance, the author didn’t sit down and say, “I am going to write a poem in one hour. It should contain 2 emotions, and 280 syllables. It should refer at least once to a balloon, because balloons make people both happy and sad. Ready? Go!”

Shane Jones didn’t say it took him an unusually short time–only ten hours!–to write his short story. Maybe that’s what he meant, but it read to me as if he were suggesting that the time spent on the story was typical for him.

I agree in general that it doesn’t matter whether a work is a novella or a novel, except that in this case, he is shouting from the HTMLGIANT rooftops that this is how is managed to write his NOVEL in 40 days, a feat that sounds quite impressive and important until you note

that that’s less than 1,000 words a day. Completing any literary work is a great feat, even if it’s being treated like a 40 yard dash. Even still, a trace of uncertainty would go a long way here. And what exactly is it about this 40,000 words that makes it feel like a novel and not a novella? I suspect that it’s simply that “novel” sounds so much better. So I guess I’m just reacting to the pretension and absurdity of that.

I wish journals and presses were open to longer works. I tend to write longer things myself. My stories are usually well over 3000 words, and as such I’ve essentially given up trying to publish them in journals. And my first novel was 100,000 words long, 400 MS pages, and the press that published it had to reformat it to fit on 300 pages so they could bind it.

Stuff’s getting shorter and shorter. Capitalism probably has something to do with it.

For the longest time I thought 240 pages was the perfect length for a novel because that’s how long Wittgenstein’s Mistress is. But my pal Jeremy M. Davies’s 2010 novel Rose Alley is 178 pages long, and it’s brilliant and well worth the MRSP of $15.95. Each page is worth at least two pages of most normal novels. (And I don’t say that because Jeremy is my pal; his writing really is brilliant.)

Cheers,

Adam

Oh, it’s totally super-short. The font is like 18pt; if it were reformatted at 12pt, the book would be maybe 20 pages long, at best.

But that’s the thing about the term “novel”: there is no real official guideline that delegates what is and isn’t one. And that’s my whole point. We’re not discussing something involving objective agreement. Again, it’s not like making Camembert: authors and publishers don’t have to follow particular rules here. If they call something that’s 5000 words long a novel, it’s not like the literary police come and pull it off the shelves at Barnes & Noble.

The more interesting question to me is: what is the force or consequence of calling something a novel? As opposed to a story? (That’s whether it’s long or short.) And I don’t think that question can be answered simply by running word count in MS Word.

Marguerite Duras felt that La maladie du mort was un roman. She called it one. She published it as one. Granted, she was drinking like seven bottles of wine a day at the time, but I think her artistic decision is interesting and well worth considering. And what’s less interesting, to me, is raising one’s hand and saying, “Excuse me, teacher, but 5000 words is not a novel!” I mean, why be so pedantic? What does it get you in this instance? (I ask this in all genuineness.)

Cheers,

Adam

Hey traynor,

I think you misunderstand me, and I’m sorry if what I’ve written here has contributed to that misundertanding. I’m not trying to shout anything anywhere. HG has no rooftop, for all I know.

I wrote a longform fiction project (I consider it a novel myself but feel free to consider it not one, even though you’ve also not read a word of it, of course), and it took me 40 days to write it. It took me 40 days because it took me 40 days. In my experience, different projects take different amounts of time—like I said in the first post, my first novel took me 10 years to write. This new novel was very different than my first novel. For one thing, it was much easier to write. I don’t think that makes it any less good. In fact, I think this new novel is better than my first novel—more successful aesthetically, and much more pleasing to read. Time expended does not always equal quality,

But in any case, I can say that I worked very hard on the l.f.p. during those 40 days, as I take writing very, very seriously—indeed, I’ve devoted my entire life to studying it and to doing it as well as I possibly can. I’m even getting my third degree right now in it, a PhD which, believe me, takes up just about all my time and energy. I’m, like, totally committed to writing. But all that being said, maybe this new l.f.p of mine is a total piece of crap? Others are free to think of it what they like, though I do know that I can account for why I made it the way that I did.

In this particular series of posts, I’m trying to document what I did in writing this project, but not because I think I’m some amazing writing god or anything. Indeed, I considered not writing/posting this series because I was worried that people would mistake the posts for self-aggrandizement. And I’ve been blogging for over four years now, and I think I’ve demonstrated in that time that I’m not really one for self-promotion? I rarely ever talk about my own writing.

But I chose to write this series after all, because I want to write more about craft, and I think it makes sense to write about something where I can account for the choices I made. Rather than analyzing something that someone else has made (as I do 99% of the time).

Meanwhile, I don’t think I’ve made any big deal out of the fact that it took me 40 days? I don’t really consider that remarkable. It took the length of time it took, no more, no less. And I also don’t really care if others call the finished product a novel or a novella, because I don’t think anything’s really at stake in that distinction. I myself tend to not use the word “novella,” but that’s because I don’t think it really means much of anything—the criteria for it are all over the map, and I don’t see why it’s functionally dissimilar from, say, “short novel.” Which my new l.f.p certainly is—150 pages is pretty short! But I do think the project ended up being around the exact number of words it needed to be. And that’s what really interests me: how I went about determining how long it should be to function aesthetically, and then how I went about making it that length. You can safely assume that my focus is entirely on craft.

But like I said above, feel free to call this new project a novella if that’s some super-important thing to you. Actually, at the moment it’s a Word file on my laptop. Who knows if it will ever be published? I don’t think that really matters all that much. (Meanwhile, if you really are so obsessed that anything under 80,000 words long not be called a novel, perhaps you can explain to me why you’re so passionate about that? Because I really don’t get it. And I say this in all curiousness. Explain your passion to me!)

Anyway, I’ll restate here that my goal in these posts is to demystify the writing process (my writing process) as much as I can. I am not trying to be pretentious or absurd; I don’t think I’m all that pretentious a person, honestly (though I can be absurd). And I’m trying to document what I did in the sincere hope that my process and methods will interest and be of use to other people. Of course they may not be. And like I said in the beginning, maybe people will want to do the exact opposite of what I’ve done! That would be cool.

I think you try reading what I’ve written here more charitably, you’ll see all that. Or I hope that you will. But if I’ve given the opposite impression, I regret that.

Cheers,

Adam

Hey Adam, Sorry to make it seem like a personal attack. I didn’t intend to be unkind. I *might* become argumentative in comment sections. I usually avoid them for the sake of my karma. I don’t have a larger objection other than the one I’ve already written, that I sense a greater disposability and a more casual attitude toward the question of quality among the writing that is produced by some people who see themselves as working outside of traditional publishing. And something in your post (and in the Shane Jones post I cited) called that to mind for me.

As to the question of length, I guess I’m just wondering if you acknowledge the existence of novellas. Are there such things as novellas on the planet? If so, why is your book NOT one of them?

Obviously, you are free to call your piece of long fiction whatever you wish, but did you consider calling it a novella, then reject that notion for some reason?

it’s not that I’m particularly passionate about the question, but if someone describes a goat to me and then calls it a cow, I wonder why. Maybe there’s compelling evidence that the goat should be called a cow. I just wondered.

I understand your position that there’s no governing body or “official” verdict on what is and isn’t a novel, but it seems as though you’re being willfully ignorant of the fact that there is general consensus on this question. Just google “What is the length of a novel”. I’m not making this stuff up. :)

One of my favorite books is Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow. I don’t know how long it is, but it’s very short, and I do think of it as a novel. I’m not entirely certain why. Probably just because it’s packaged that way. But I wouldn’t have thought twice if I had noticed it was the long story in a short story collection. I imagine they probably called it a novel because it would reach more readers and make more money that way.

Hi traynor,

Of course I acknowledge that novellas exist! I own many books with that word on the cover. For instance, Lore Segal’s brilliant Lucinella, which I highly recommend if you haven’t read it.

The thing is, though, even though you write that there’s a “general consensus” as to how long a novel is…there isn’t. Nor is there any “general consensus” as to what distinguishes a novella from a novel. Rather, those distinctions are very arbitrary. In the 15+ years I’ve been studying writing, I’ve encountered a wide variety of criteria for both, to the point where it seems to me that the discussion is characterized more by disagreement than agreement. In other words, it’s nothing at all like distinguishing between a goat and a cow, because those are distinct animals that usually aren’t confused by people. There isn’t an ongoing debate over which is which.

But consider Lucinella alone. Melville House Press reprinted it in 2009 as a novella. But the original printing in 1976, by FSG, was labeled a novel. And the author, Lore Segal, refers to it as a novel at her website. And that’s just a single example. (Meanwhile, neither the contents of the book, nor its brilliance, have changed in any way.)

As such, the novel/novella debate has never really interested me all that much, because 1) the length arguments seem entirely arbitrary (again, there’s no “general consensus”), and 2) as I stated elsewhere in this thread, I fail to understand what’s at stake in making such a distinction, especially given the wide range of word counts / page numbers invoked. Why is it so important that some works be called novellas? I do recognize that some folk are adamant about that distinction, but I’ve never seen a convincing argument as to why—instead it strikes me as pedantry more than anything. (But like I said before, if you think there’s a vital reason for labeling certain works novellas, please do explain it to me! I’m all ears.)

Me, I tend to think of novels as being works of fiction that are longer than stories and intended to be read in more than one sitting (to which end they usually contain chapter breaks). A novella, then, if I had to define it, would be something between a novel and a story, possibly a very long story that isn’t like a novel but that is meant to be read in maybe two sittings? But I dunno. Again, it’s not a distinction I’ve spent much time thinking about, or feel very invested in. It seems to me if anything that “novella” is an older term that was once more important (when novels tended to be much longer on the average), but that has become less necessary or important in the past 100 years, and is now not used consistently. But I haven’t studied the issue carefully and could be wrong about that.

I get the impression that you consider novels somehow better or more important than novellas? (“I imagine they probably called it a novel because it would reach more readers and make more money that way.”) Or perhaps you’re saying that others make such a distinction. Me, I do not share that bias in any way. Instead, what matters to me is formal unity: works should be the length they are because they cannot be any other length and achieve the intended aesthetic effect. A great short story, if it is great, is just as great as a great novel, theoretically speaking. In any case, when I called my new project “a novel” I wasn’t trying to puff myself up or anything. I didn’t consider calling it a novella for even a second, due to the reasoning I’ve laid out here. But that had nothing to do with my thinking that novels are better or more important than novellas, or vice versa. (If anything, I get the impression that novellas are considered pretty hip these days, thanks to MHP?)

Today, the novella / novel distinction seems mostly to do with how books are marketed, which doesn’t interest me all that much, and has no relevance to this present series (which is describing how I wrote something that hasn’t been published yet, and may never be published). Hence, Lucinella was reprinted as a novella because that’s how MHP wanted to market it, as opposed to how FSG wanted to market it almost 40 years ago. But marketing distinctions have to do with how books are sold, not how they are written, and the decisions authors made in making them. If, later on, some press wants to publish this new MS of mine, and wants to call it a novella, then I’m not going to put up a fuss. Because that won’t have anything to do with the work’s quality, or how I wrote it, or why I made it the way that I did. And the latter is what I’m trying to discuss in this series. My passion is for craft, and achieving the strongest aesthetic effect possible. My interest is in art.

I hope this clarifies my thinking, and where I’m coming from! I really do appreciate your comments, and am now more interested in the history of the novella than ever before!

Cheers,

Adam

Thanks for the reply. You say, “I didn’t consider calling it a novella for even a second, due to the reasoning I’ve laid out here,” but I didn’t really see you lay out any reasoning specific to your book. You basically just repeated that you don’t know what’s at stake in making

the distinction, and that you wonder why others feel that anything is at stake at all. Oh, and that there is no consensus about what makes for a novel-length manuscript–that one I really disagree with. Not because I give a shit particularly, you understand, but because if I Google it, I come up with a consensus. We could Google it together, but I don’t think it’s worth either of our time.

It feels a bit like projection to say that I might think of novellas as lesser works than novels. You’re won’t even entertain the possibility that you might have written one.

I understand that you are invested in calling it a novel–perhaps for a reason you don’t feel like sharing–and that, I suppose is reason enough to call it one. I like novellas, I like novels. Either way, I sincerely wish you every success with it, and I hope it’s very good, because I am always happy to read very good work, whatever its length.

novella length for whatever reason seems to be more firmly defined (17,500-40,000) in the SFF field. not sure about other genres. novellas don’t seem to be as common in lit fiction (if you will, and if adam’ll allow me to categorize his lfp w/o my having read it), and i dunno if there are major prizes awarded to them as a category (there are hugo, world fantasy, etc awards for novellas in SFF), so i dunno that a particular word-count range has really taken hold as being the definite length of a novella in lit-fic circles. a few google searches give me no evidence of consensus on the length of a novella if i exclude reference to SFWA or RWA prize guidelines.

that said, if i were adam’s publisher i’d likely be inclined to publish it as a novella. and i agree w/you, traynor, that there seems to be a small trend in, i dunno, small press or indie or alt lit or whatev to call something that’s like 31,000 words a novel. i dunno if it’s a grab for cheap gravitas or what.

that said, i agree with adam that there’s not much at stake in the distinction. and it seems pretty obvious to me he’s not looking for cheap gravitas by calling his work a novel.

Yeah, the definition of a novella is hazier than the definition of a novel, for sure.

This is an interesting tidbit on the subject of novellas:

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2012/10/some-notes-on-the-novella.html

Ian McEwan writes:

“Let’s take, as an arbitrary measure, something that is between twenty and forty thousand words, long enough for a reader to inhabit a world or a consciousness and be kept there, short enough to be read in a sitting or two and for the whole structure to be held in mind at first encounter—the architecture of the novella is one of its immediate pleasures.”

Wikipedia’s entry on word counts lists 40,000 as the bottom end for a novel, which kind of surprises me, actually. But of course, anyone could have written that.

EDIT: It seems worth saying that this is not an issue about which I care deeply. I was just curious why the subject isn’t even up for debate here.

-Anyone know how long Barry Hannah’s Ray is? That seems like a fine length for a novel.

-I’m enjoying these posts a lot! I like explanations of structure and method, particularly from someone who determines the constraints of the novel before it begins. Do you worry at all that it might be too structured — that by having moderately strict expectations of the novel it’ll stunt your creativity? Or is that the sort of thing you’re looking to demystify?

-Heathen is a pretty good David Bowie album! I started listening to him during the Reeves Gabrels era (Earthling/hours…) which, looking back on it, were not his best.