Word Spaces

Venus & Jupiter: The Conjunction of Brown & Powell

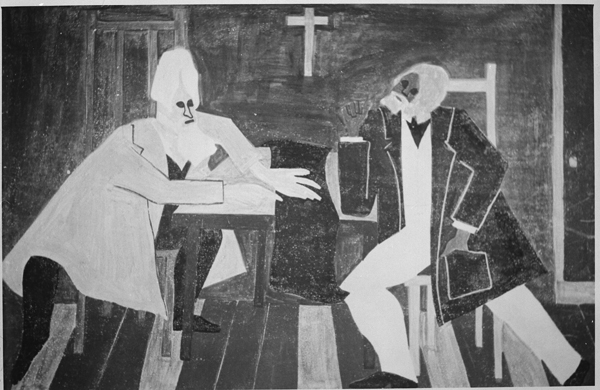

Frederick Douglass argued against John Brown’s plan to attack the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Jacob Lawrence

One hundred and fifty years ago, a man named John Brown was put to death by the state. He was not gunned down in the street, nor was he unarmed. He was arrested by Robert E. Lee for leading a raid on the national armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. He had planned to arm America’s slaves with a hundred thousand guns. He was a white man, a preacher. Newspapers called him “a madman.” In most pictures he had “crazy eyes.” Abe Lincoln declared him “insane.” One thing’s for sure, he was mad. His rage boiled over.

American poets compared Brown’s life to a meteor that tore across the sky as he sat in jail, very nearly bisecting the interim of his conviction and execution. Emerson called him a saint, “whose martyrdom, if it shall be perfected, will make the gallows as glorious as the cross.” Thoreau said, “When a man stands up serenely against the condemnation and vengeance of mankind, rising above them by a whole body . . . the spectacle is a sublime one.” Both had attended his speeches and probably knew about the raid before it happened. Years later, Melville wrote, “the streaming beard is shown / (Weird John Brown), / The meteor of the war.” Whitman, who was there, put him in Leaves of Grass: “YEAR of meteors! brooding year! / I would sing how an old man, tall, with white hair, mounted the scaffold in Virginia; / (I was at hand—silent I stood, with teeth shut close—I watch’d; / I stood very near you, old man, when cool and indifferent, but trembling with age and your unheal’d wounds, you mounted the scaffold;)” The actor John Wilkes Booth was there, too. He wrote his piece in Lincoln’s blood.

Even Victor Hugo, in exile, called for Brown’s pardon. “There is something more frightening than Cain killing Abel,” he said, “and that is Washington killing Spartacus.”

While planning the raid, Brown asked Frederick Douglass to join him. But Douglass thought America needed a nonviolent revolution, and he tried to convince Brown to stay in the pulpit. He thought slaveholders could be “converted.” But Brown refused to believe that people of such moral debasement could be saved. According to Douglass, Brown said, “they would never be induced to give up their slaves, until they felt a big stick about their heads.” Douglass later wrote that Brown’s cause was “the burning sun to my taper light – mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity.” The raid, and Brown’s execution, arguably sparked the Civil War.

At the end of the war, a black college was founded a few miles from the armory at Harpers Ferry. Douglass was asked to speak at its fourteenth anniversary. Sharing the platform with Brown’s prosecutor, he answered a question that had been asked of the raid many times before:

… the question is, Did John Brown fail? He certainly did fail to get out of Harpers Ferry before being beaten down by United States soldiers; he did fail to save his own life, and to lead a liberating army into the mountains of Virginia. But he did not go to Harpers Ferry to save his life.

The true question is, Did John Brown draw his sword against slavery and thereby lose his life in vain? And to this I answer ten thousand times, No! No man fails, or can fail, who so grandly gives himself and all he has to a righteous cause. No man, who in his hour of extremest need, when on his way to meet an ignominious death, could so forget himself as to stop and kiss a little child, one of the hated race for whom he was about to die, could by any possibility fail.

On August 9, 2014, as the Missouri sun crept past its zenith, a white police officer named Darren Wilson pulled up behind two black men, Mike Brown and Dorian Johnson, who were walking on the street. The officer ordered them to get on the sidewalk. After a confrontation, Wilson shot Brown six times. Five of the shots were fired after Brown ran away. According to Johnson, Brown had his hands up and stated that he was unarmed. One of the bullets entered the top of Brown’s head. He was 6’4″.

The next day, protests began, as did civil unrest. The situation intensified when Ferguson Police refused to identify the homicidal officer for six long days, during which time a meteor shower danced softly in the night. Three days later, Venus and Jupiter formed a conjunction. They appeared, like very bright stars, side by side. But of course, they are not stars — they are planets. Their light shines not from within, but without, reflecting the ancient light of our own bleeding sun, about which we relentlessly sway.

A day later, two St. Louis police officers shot and killed Kajieme Powell a few miles from the site of Brown’s shooting. He stole two sodas and a honey bun, presumably ate the honey bun, put the sodas on the ground, then waited for the police. In a cellphone video, he paces back and forth, saying, “I’m on Facebook. I’m on Instagram. You know who I am? I’m tired of this shit.” Someone yells, “Yo this is not how you do it, bruh.” When the police show up, they immediately draw their guns. No attempt is made to talk him down. They just yell orders at someone who is clearly tired of being told what to do. He approaches them, shouting “Shoot me, shoot me.” And they do. Then they roll his dead body over and handcuff his lifeless wrists. They willfully ignore the potential witnesses, including the man with the cellphone. “Someone should call the police,” he says, as they pull yellow tape across the screen.

It’s one of the most harrowing videos I’ve ever seen. It’s also a postmodern moment that should not be missed. It deserves to be remembered as its own distinct injustice. But it’s been overshadowed by the events that surround it.

On two separate occasions when I asked someone if they had seen the video of the police killing a man in St. Louis, they said they had heard of it, but couldn’t watch. However, as I described the video, they soon realized I wasn’t talking about Mike Brown — I was talking about a conjunction, Kajieme Powell, someone else in almost the same space and time. The proximity is so close it obscures the difference.

Events like these rupture the social fabric, that illusory web that “holds us together,” revealing what psychologists call empathy gaps. Touré wrote about this in an op-ed for the Washington Post. We search for connections between events that may have no connections. We search for meaning where there may be none. People are asked to be victims or perpetrators, innocent or guilty, brown or white. But the truth is a mess.

Kajieme Powell has been characterized by neighbors and journalists as “mentally ill.” Personally, I don’t see that. What I do see is rage. Powell’s mental state will no doubt be established by a court of law, as will the “rightness” or “wrongness” of actions by the police. The St. Louis Police Department claim the officers acted according to protocol, and that Powell’s death was “suicide by cop,” a crude phrase that has no place in a just world.

It’s been reported that CNN has a clearer video of the event, but they stop seconds short of Powell’s slaughter, before he allegedly pulls a kitchen knife from his waist and lunges at the police in what would have been a futile attempt to take their lives. This in fact makes it less clear. But both versions make it impossible to see Powell’s actions a few seconds before he is shot. We don’t see the knife, nor the lunge. His hands appear to remain at his sides. This lack of clarity creates a gap, a sort of Doppler affect. As we approach resolution, we fall short, and so there is nowhere for our anger to go. It evaporates into a question: “What the …?” Apparently this question floats away, unanswered.

In the case of Michael Brown, there was no video. We were instead presented a void. For a long time, we didn’t even know who did it — long enough for Darren Wilson to scrub the internet of his existence. We were left to invent our own images, our own narrative. Subsequent images and lack of images only served to further this invention. Depending on one’s race, class, experience, and politics, the narrative manifested in myriad ways while appearing not to move, like a swamp.

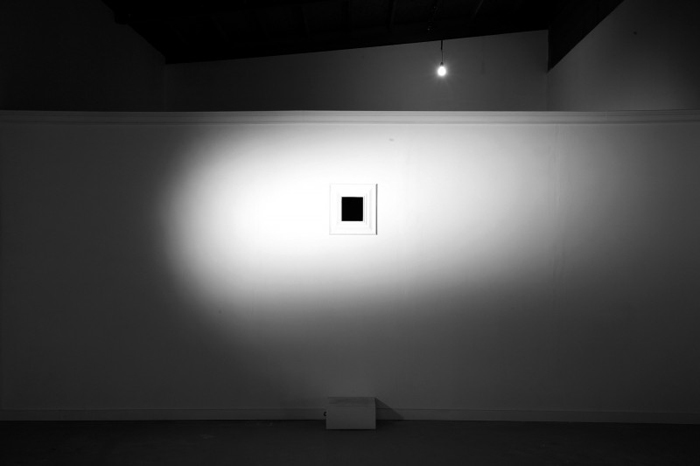

White Malaise, or Jupiter Rebuked by Venus, Abraham Janssens

William Pope.L, who calls himself “the friendliest black artist in America,” wrote, “Holes are not the point. / Holes are empty theory. // When I say– / Hole theory explains nothing / This is only in order to create / A platform from which to engage everything.” This explanation colors Andrew Beradini’s description of Pope.L’s Void Piece in the arts quarterly X-Tra:

A stage light points at the framed hole, but one lone incandescent light bulb hangs over The Void Piece, shedding light on the subject that can’t be seen. The prankster in me immediately wants to believe there might be something fantastical back there: buckets of chocolate, or an apartment for Anthony Burdin, or a hundred thousand rubber ducks, fifty mannequins in Superman costumes, Pope.L’s collection of potted cacti… (Actually, Pope.L did joke that he had finally found a way to imprison God and he’s farting on our faces from within.) All this play, though seemingly invited, seems ultimately to infer that behind the illuminated frame of the void, there is just more void: a space defined by absence.

People around the world were shocked by the militarized police response in Ferguson, but they shouldn’t be. This is far from the first time we’ve seen assault rifles and riot gear patrolling American streets.

On April 29, 1992, four LAPD officers who beat Rodney King were acquitted of assault and use of deadly force, despite clear video evidence of the event. The video played widely on television, minus the few seconds in which King fought back. Those seconds were what got the acquittal, which sparked epic riots in Los Angeles. The gap in the video signified a lack of justice, and its lack was gaping. A large group of protesters gathered in front of the courthouse and chased away the police. People were pulled from trucks and beaten in the street. One man was spray painted black. The video played so many times, Ed Turner called it “wallpaper.”

On the second day of rioting, Bill Cosby appeared on a local TV station. He asked everyone to stay home and watch the last episode of The Cosby Show. The riots lasted six days and led to more than fifty deaths, two thousand injuries, eleven thousand arrests, and a billion dollars in damage. It was as if an earthquake had split the city along faults composed of race and class.

A Special Committee of the California Legislature issued a report called To Rebuild is Not Enough. They based their findings on those made by commissions formed after civil rights demonstrations in the 1960s. They said the riots were the result of “poverty, segregation, lack of educational and employment opportunities, widespread perceptions of police abuse, and unequal consumer services,” and that “the causes of the 1992 unrest were the same as the causes of the unrest of the 1960’s, aggravated by a highly visible increasing concentration of wealth at the top of the income scale and a decreasing Federal and State commitment to urban programs serving those at the bottom of the income scale.” If a commission said the same thing today, it would be called “progress.”

Unsurprisingly, those conclusions contradicted assertions by then President H.W. Bush, who said, “What we saw last night and the night before in Los Angeles is not about civil rights. It’s not about the great cause of equality that all Americans must uphold. It’s not a message of protest. It’s been the brutality of a mob, pure and simple.” But of course, nothing is pure and simple. Things are complex and jagged. And in times like these, they fall apart.

In Bomb, Martha Wilson asked Pope.L what he wanted to get out of a performance at Franklin Furnace, in which, standing in front of a window, his butt to the street, he covered his nearly naked body with mayonnaise:

Mayonnaise is a kind of make-up. It has an impressive coverage. But the longer it remains, the more transparent it becomes. Not to mention the smell. I was interested in doing something futile. For me, mayonnaise is a bogus whiteness. It reveals its lack in a very material way. And the more you apply, the more bogus the act becomes. The futility is the magic. I wanted to poetically reconfigure the mayo. Sometimes the things we take for granted are the things that are most dear to us. Like, for me, mayonnaise and peanut butter, those “cheap” foods we ate as kids . . . I like these materials. This brown goo, and its evil twin, this . . . white goo. Once used, they don’t stay in their original form: they change, they oxidize . . . Which leads to an interesting query: What is brownness as opposed to whiteness? Mayonnaise gave me a quirky material means to deal with issues black people claim they don’t value very much, e.g. whiteness. Black folks’ political and historical circumstances are at odds with whiteness, whether we want them to be or not. There are societal limitations to how much one can reconstruct one’s conditions. We are born into whiteness. On the surface, it seems wholly to construct us, and the degree to which we may counter-construct sometimes seems very limited. But, I believe we can be very imaginative with limitations. And I am lucky that today I can hold that point of view . . . Mayonnaise was a very useful and fresh way for me to get out of this dead end: whiteness constructs blackness. Mayo and peanut butter allow me to think about race in a more playful, strange, and open-ended way. For example, the idea that there’s a pure good blackness or a pure bad whiteness is untenable for me. I use contradiction to critique and simultaneously celebrate.

After writing this essay, I was driving home from a bar when I heard James McBride talk about his novel The Good Lord Bird, which won last year’s National Book Award for fiction. Somehow I missed it. It’s a satire about John Brown, who “saves” a black boy from a bar. The boy is dressed in a potato sack and John Brown thinks he’s a girl. The boy doesn’t correct him. He joins Brown on the raid at Harpers Ferry, and lives to narrate the novel after a lifetime has passed. Listening to the interview felt like dreaming.

In dreams, I often fall. When I’m awake, I think back on this falling, which seems to imply a certain doom. But the scary part, it seems to me, is the uncertainty: where or when will I land? And yet, in the moment, in the middle of these dreams, I don’t feel afraid. I just fall. I don’t look down, because it doesn’t matter. Maybe on some basic level I know that I’m not real. So there is no scary part. That’s just a memory. But the memory and its actuality are so close it obscures the difference.

We don’t know what we’re headed towards or why, and we don’t know what it will look like when we get there, or what it will mean. But there are things we can do on the way down, real things that will matter to other people. Like it or not, we have choices to make: who to vote for and why; what to read or watch, buy or not buy; whether or not to nod at someone on the street, in order to acknowledge their being there and then. And in those moments you are most definitely not dreaming. You’re not falling. You are there, and so are they. Everyone is people. Even you.

Tags: a brief history of swamps, ambiguity, Conjunctions, john brown, kajieme powell, mayonnaise, michael brown, the problem with images, the void, william pope.l

really well done, Reynard. thank you.

I’m interested in doing something futile.

If you–anybody–saw video of Darrell Wilson – whom it would be foolish to scruple to call a murderer – pushing around another man and stealing shit from him, would you reason that any conflict he found himself in a few minutes later was entirely imposed on him?

Before Kajieme Powell was murdered – while he was trying to say his piece on the sidewalk before the police stormed up – , was paying for shit part of what he was tired of? part of being told what to do that he was tired of?

I didn’t call Wilson a murderer. I said he was homicidal. Brown’s death was ruled a homicide. I’m not going to answer your question though, because it’s stupid.

I didn’t say Powell was murdered either. I said he was slaughtered, as in manslaughter, which is what police have been charged and convicted of before, along with excessive use of force. I can’t speak to his thoughts, obviously, but I feel that his shoplifting was an act of civil disobedience.

I called Wilson a murderer and Powell, a murder victim; neither characterization was of your point of view.

In calling his theft from a shopkeeper “civil disobedience”, you imply that Powell was ‘stupid’. I think it much more likely that he was ‘crazy’ than stupid, but that’s parallax for you.

How seriously do you take this ‘perspective of perspective’?

I would never suggest that all shoplifting is civil disobedience. Acts of civil disobedience rely on their context. Powell didn’t just shoplift, he did so in a certain context and then he made a certain show of it. His actions place it in a political realm, rather than I guess an economic realm. It seems clear to me that, whether or not he was “emotionally disturbed” or “mentally ill,” he was protesting systems of repression and oppression.

I called your question stupid because I feel it lacked intelligence and common sense, not “logic.” I see your logic, but I think it’s mangled in its unfortunate attempt at clarity. And yes, I fully believe that things are complex and jagged.

You’re imagining insinuations; my comment wasn’t a sly–or any other kind of–attack against your point(s) of view, but rather, an attempt to complicate the general (“you–anybody–”) Left take on these events.

The point of the Brown/Wilson question was to ask after what I think Wilson’s (courtroom) defense will be: that Brown escalated a verbal interaction into a physical fight. (–which I think he probably did.) The Right point of view – that therefore Brown had execution coming – is to me as irrational as it is immoral. But nor is the wantonly-shot-an-unarmed-child narrative (general on the Left) complicated enough.

Why do you think Powell was (I’d call it) political-economically ‘protesting’? From this account, it seems he was punking a shopkeeper, not sticking it to the Man. And if this shoplifting was practical critique, I’d call it ‘stupid’. Rather, I suspect that Powell was spiraling out of control (though maybe using the language of political-economic protest), and not taking an actual, though stupid, political-economic stand. What evidence do you have that Powell was protesting oppression?

That account seems pretty bad to me. Bad in that they probably got all of their ‘evidence’ from police statements. I have no evidence to support my claim, except I guess my own interpretation of his actions as seen in the video, which only exists inside my head. I don’t really know why you want to split hairs on this, but I’m done.

As you know, I didn’t call Brown a child. I think that characterization is absurd.

Yes, the narrative that a ‘child’ was shot down in the street infantilizes Brown. Again, I was not characterizing your point(s) of view; I was repeating, in a well-signposted way, a bit of rhetoric widespread at least until that surveillance video was ‘leaked’, which wording and attitude are, in my view, a poor way to contest the malicious he-had-it-coming rhetoric that would pretend to defend Wilson.

It seems to me that that newspaper report might’ve been gotten partly from direct contact with the shopkeeper (?) and other witnesses (??). In my view, it comports well with the audio on the video you’ve linked to–until the police roll up.

I understand defensiveness, and I understand aversion to discomfort; I can see the point of them. It is not splitting hairs, and it is not crap, calmly and impersonally to question after somewhat obscure but emotionally explosive circumstances and clearer–simpler–reactions to them.

Assimilating emotions that the Brown and Powell murders seem to disclose (and churn up) to John Brown’s rage will invite conversation — and resistance to “debate”. The last, to the extent that I believe it, I don’t understand.