Craft Notes

Grammar Challenge: Answers and Explanations

The answers to the other night’s grammar challenge appear haphazardly throughout that post’s comments section, but it seems like people are still taking it, so I thought I’d hide the answers here under the fold for ease of checking.

Here is the essay “Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars over Usage” that Wallace published in Harper’s in 2001. Those of you who give knowing the rules a bad name by correcting other people’s spoken and casual English really need to read this. So do those of you who think fiction writers and poets don’t need to know the rules. Both groups are lazy. It’s lazy to learn some rule in elementary school and continue to lord it over people while failing to pay attention to shifts in usage. And it’s lazy to distract readers unnecessarily because you don’t realize that your misplaced adverb causes ambiguity. Every writer would do well to invest in a copy of Garner’s Modern American Usage. I took quite the browbeating from Wallace before I bought mine for putting “over all” (should be one word) in a story. And yes, the shakedown took place in Footnote 7 in his letter of critique.

But Wallace would recommend another, older essay–the one that inspired his own subtitle, George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language.” Read that here.

Answers to worksheet, once you’re ready, are below.

1. He and I hardly see one each another.

“One another” is used for a noun that is three or more in number; “each other” is used for two. Many commenters took umbrage with the use of “hardly,” arguing that “hardly see” means some kind of visual impairment, but I don’t find any support for this idea. This is also why I emphasized that each sentence has one main error–all of them could surely be edited in other ways, too, but the real–to use Wallace’s word–boner here is “one another.”

2. I’d cringe at the naked vulnerability of his sentences left wandering around without periods and at the ambiguity of his uncrossed “t”s.

This is a parallelism problem. The subject cringed at two things; the intervening prepositions “of” and “without” cloud the meaning without the repeated “at.” Lots of people put a comma before and, but that is a nonstandard way to improve clarity.

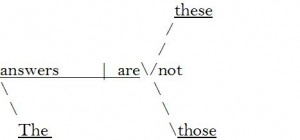

3. My brother called to find out if whether I was over the flu yet.

If you can use whether, always do so. If implies conditionality. Whether or not is redundant.

4. I only spent only six weeks in Napa.

The adverb only modifies six, not spent. If it modified spent, the sentence would be implying that the subject didn’t, say, work or weep or dance six weeks in Napa–merely spent six weeks there. Clearly, not the author’s intention. Wallace had a funny way of teaching this:

You have been entrusted to feed for your neighbor’s dog for a week while he (the neighbor) is out of town. The neighbor returns home; something has gone awry; you are questioned.

“I fed the dog.”

“Did you feed the parakeet?”

“I fed only the dog.”

“Did anyone else feed the dog?”

“Only I fed the dog.”

“Did you fondle/molest the dog?”

“I only fed the dog!” [Here Wallace’s voice cracked funnily.]

5. In my own mind, I can understand why its implications may be somewhat threatening.

You can understand something only in your own mind.

6. From wWhence had his new faith come?

Grossly redundant. Whence means from where.

7. Please spare me your arguments of as to why all religions are unfounded and contrived.

Idiom error.

8. She didn’t seem ever to ever stop talking.

Don’t split infinitives if you can easily avoid it. Here you can easily avoid it without sacrificing meaning or elegance of expression.

9. As the relationship progressed, I found her facial tic more and more aggravating irritating.

As I explained in the comments section: Aggravating was a special peeve of Wallace’s, since you could just as easily use irritating and thereby not, ahem, irritate readers who believe that aggravate should only mean to make worse. Again, his thing was that if you can use a synonym that doesn’t come with a fraught usage history, you should, because you never want readers to be distracted in that particular way. This distracting-the-reader caution is in the essay linked above.

10. The Book of Mormon gives an account of Christ’s ministry to the Nephites, which allegedly took place soon after Christ’s his (or His) resurrection.

Simple rule, avoid needless repetition.

In a kind of fit I revealed answers sooner than I intended, which makes judging difficult for those who apparently didn’t see those answers and still tried on their own. So, thanks to everyone who tried, but I think the winners are two early commenters, our own Ryan Call and the anonymous “Michael,” who I called David a few times. They each got 2 before anyone else and they kind of collaborated on a 3rd. I don’t know what they win yet. Ryan and “Michael,” what would you like to win?

Tags: david foster wallace, grammar, usage

#8 sounds horribly antiquated and awkward with the grammar fix.

#8 sounds horribly antiquated and awkward with the grammar fix.

I agree with this.

I loved this feature though Amy!

I agree with this.

I loved this feature though Amy!

yes. more please.

yes. more please.

wait, who fed the fucking dog again?

wait, who fed the fucking dog again?

well the instructions do say you should be able to AVOID or repair the clauses; avoiding that construction altogether would be probably be ideal, but the split infinitive was the reason for its inclusion on the WS

well the instructions do say you should be able to AVOID or repair the clauses; avoiding that construction altogether would be probably be ideal, but the split infinitive was the reason for its inclusion on the WS

Orwell’s essay on language is one of my all-time absolute favorite things.

Orwell’s essay on language is one of my all-time absolute favorite things.

just read the wallace essay in harper’s. it’s pretty damn clever. worth a look.

just read the wallace essay in harper’s. it’s pretty damn clever. worth a look.

also:

what about ‘i fed the dog only’ ? i’ve heard/used it that way in the past. is it unclear what only modifies and is therefore incorrect?

also:

what about ‘i fed the dog only’ ? i’ve heard/used it that way in the past. is it unclear what only modifies and is therefore incorrect?

Just looked it up in Garner…he says the best place to put only is right before what it modifies. He doesn’t get into its possible placement at the end of a sentence, thus modifying whatever word is before it, but there is an interesting anecdote about how certain uses of “only” after what it modifies can be a form of doublespeak: An American Airlines sign c. mid-1990s read “Beverages only in main cabin.”–which gives the sense that the coach passengers are getting something nobody else gets, whereas what it’s really saying is that no meal is served in coach (just first class).

Just looked it up in Garner…he says the best place to put only is right before what it modifies. He doesn’t get into its possible placement at the end of a sentence, thus modifying whatever word is before it, but there is an interesting anecdote about how certain uses of “only” after what it modifies can be a form of doublespeak: An American Airlines sign c. mid-1990s read “Beverages only in main cabin.”–which gives the sense that the coach passengers are getting something nobody else gets, whereas what it’s really saying is that no meal is served in coach (just first class).

makes sense, thank you.

really good feature. now i’m second-guessing everything i type, which is both good and bad.

makes sense, thank you.

really good feature. now i’m second-guessing everything i type, which is both good and bad.

Hey since when am I anonymous?

I’d like to win a signed copy of “Scorch Atlas,” by one B. Butler.

Hey since when am I anonymous?

I’d like to win a signed copy of “Scorch Atlas,” by one B. Butler.

“Clearly, not the author’s intention.”

So there is no ambiguity in this case, right?

“Clearly, not the author’s intention.”

So there is no ambiguity in this case, right?

but again, the error is distracting even if the meaning eventually becomes perfectly clear.

but again, the error is distracting even if the meaning eventually becomes perfectly clear.

“Eventually”?? How is it possible to misread that sentence?

Do you really mean to argue that saying one spent a certain amount of time somewhere implies one didn’t do anything during that time? Didn’t “work or weep or dance” but “merely spent” the time? What does it mean to merely spend time?

Sorry to be argumentative, but since you’re setting yourself up as a champion of rigor here it doesn’t seem unreasonable to ask you to come up with a coherent way to defend your position.

“Eventually”?? How is it possible to misread that sentence?

Do you really mean to argue that saying one spent a certain amount of time somewhere implies one didn’t do anything during that time? Didn’t “work or weep or dance” but “merely spent” the time? What does it mean to merely spend time?

Sorry to be argumentative, but since you’re setting yourself up as a champion of rigor here it doesn’t seem unreasonable to ask you to come up with a coherent way to defend your position.

the adverb should modify the part of the sentence it is trying to modify. The fact that this normally wont’ be misread doesn’t make it not an error. Cna yuo raed this setnence?

Or should immediately precede the part of the sentence it is trying to modify.

the adverb should modify the part of the sentence it is trying to modify. The fact that this normally wont’ be misread doesn’t make it not an error. Cna yuo raed this setnence?

Or should immediately precede the part of the sentence it is trying to modify.

dude, i’m merely telling you the answers that David Foster Wallace gave in class and explaining them a bit. his essay, which i linked to above, gives an explanation of the reader-distraction position.

thanks, lincoln, very nice examples.

dude, i’m merely telling you the answers that David Foster Wallace gave in class and explaining them a bit. his essay, which i linked to above, gives an explanation of the reader-distraction position.

thanks, lincoln, very nice examples.

Lincoln,

First of all, it’s not true that adverbs have to be placed in front of the word or phrase they’re meant to modify. Trust me.

In the second place, I wasn’t the one who put forward the standard of avoiding possible misreading. It was offered above as a rationale for the rule that I am disputing. But since there is no possible misreading of the sentence cited as an example, the rationale offered wouldn’t apply to the case at hand. Can you propose another one that would?

In fact it is perfectly idiomatic in many (though of course not all) cases not to put only right in front of what it’s modifying.

Lincoln,

First of all, it’s not true that adverbs have to be placed in front of the word or phrase they’re meant to modify. Trust me.

In the second place, I wasn’t the one who put forward the standard of avoiding possible misreading. It was offered above as a rationale for the rule that I am disputing. But since there is no possible misreading of the sentence cited as an example, the rationale offered wouldn’t apply to the case at hand. Can you propose another one that would?

In fact it is perfectly idiomatic in many (though of course not all) cases not to put only right in front of what it’s modifying.

Amy McDaniel,

If there are readers who let themselves get distracted by idiomatic English usage, I would say that’s on them. But that’s a matter of taste. So is choosing to admit when you can’t defend a line of argument.

If you’re citing DFW as an authority on this question, let me point out that I’m not the only one who disagrees with him. Fowler’s article on this point is sensible, and for an empirically minded contemporary analysis of the controversy you can consult Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage.

Amy McDaniel,

If there are readers who let themselves get distracted by idiomatic English usage, I would say that’s on them. But that’s a matter of taste. So is choosing to admit when you can’t defend a line of argument.

If you’re citing DFW as an authority on this question, let me point out that I’m not the only one who disagrees with him. Fowler’s article on this point is sensible, and for an empirically minded contemporary analysis of the controversy you can consult Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage.

Alan,

Well, I would hate to think that I’m “botanizing upon [my] mother’s grave” or “clapping a strait waistcoat upon [my] mother tongue.” Thanks for the Fowler referral; I’m always happy for an opportunity to consult my MEU. But Wallace is not the only empirically minded expert who detracts from Fowler; so does Garner, who notes that Fowler was “surprisingly permissive.” I agree that it is a matter of taste, but I personally prefer to avoid offending my reader’s taste where possible, and since “only six weeks” will offend exactly nobody, that’s the one I would choose. After two workshops with Wallace I’m quite won over to the Respect the Reader school of thinking on these matters.

But again, the point here is to be in control–to know the conventions, which clearly you do–and apply them, or not, purposefully and consistently. That way, if you do have a character that is hyper-correct in matters like these, you can put the right words in that character’s mouth. Wallace’s great example of this was the expletive “that.” Most people don’t use it in dialogue–but an Oxford don-like speaker does, and even Oxford dons may appear in fiction.

Alan,

Well, I would hate to think that I’m “botanizing upon [my] mother’s grave” or “clapping a strait waistcoat upon [my] mother tongue.” Thanks for the Fowler referral; I’m always happy for an opportunity to consult my MEU. But Wallace is not the only empirically minded expert who detracts from Fowler; so does Garner, who notes that Fowler was “surprisingly permissive.” I agree that it is a matter of taste, but I personally prefer to avoid offending my reader’s taste where possible, and since “only six weeks” will offend exactly nobody, that’s the one I would choose. After two workshops with Wallace I’m quite won over to the Respect the Reader school of thinking on these matters.

But again, the point here is to be in control–to know the conventions, which clearly you do–and apply them, or not, purposefully and consistently. That way, if you do have a character that is hyper-correct in matters like these, you can put the right words in that character’s mouth. Wallace’s great example of this was the expletive “that.” Most people don’t use it in dialogue–but an Oxford don-like speaker does, and even Oxford dons may appear in fiction.

OK, I do see and can respect that point of view.

I should mention that these posts were a total treat for me, both for their inherent interest and for the insights they offer into DFW’s mind and teaching style. How lucky you are to have had that experience, and I’m glad you chose to share a little bit of it here.

OK, I do see and can respect that point of view.

I should mention that these posts were a total treat for me, both for their inherent interest and for the insights they offer into DFW’s mind and teaching style. How lucky you are to have had that experience, and I’m glad you chose to share a little bit of it here.

Alan, I’m very glad to hear that you enjoyed the posts. I had fun discussing this most fine of fine points with you, Ryan, and Lincoln. Let’s play again sometime.

Alan, I’m very glad to hear that you enjoyed the posts. I had fun discussing this most fine of fine points with you, Ryan, and Lincoln. Let’s play again sometime.

Agree with all except the split infinitive. It’s a matter of pure preference. “Boldly to go where no man has gone before.”

Agree with all except the split infinitive. It’s a matter of pure preference. “Boldly to go where no man has gone before.”

I got Whence came his new faith.

that example seems different to me since it’s a mission statement, where you’d want to start every part of it with “to”–like a kind of understood sense of “(we endeavor) to _____, to ______, and to _____”, so for the pleasant repetitive sound you’d want to put the “to” first everytime. wallace preached looking at split infinitives on a case-by-case basis, as do all reasonable usage experts. i don’t have any problem with split infinitives, but readers might, and since he was teaching a writing class, he taught us to offend as few readers as possible

I got Whence came his new faith.

that example seems different to me since it’s a mission statement, where you’d want to start every part of it with “to”–like a kind of understood sense of “(we endeavor) to _____, to ______, and to _____”, so for the pleasant repetitive sound you’d want to put the “to” first everytime. wallace preached looking at split infinitives on a case-by-case basis, as do all reasonable usage experts. i don’t have any problem with split infinitives, but readers might, and since he was teaching a writing class, he taught us to offend as few readers as possible

The first “error” is, more precisely, a stylistic quibble. Consult an excellent article by the late Safire:

http://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/04/magazine/the-way-we-live-now-4-4-99-on-language-each-other.html . It presents a refreshing look at the tendency for be overly prescriptive in using the English language.

The first “error” is, more precisely, a stylistic quibble. Consult an excellent article by the late Safire:

http://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/04/magazine/the-way-we-live-now-4-4-99-on-language-each-other.html . It presents a refreshing look at the tendency for be overly prescriptive in using the English language.

Item three is also an unnecessary over-correction. As presented, the statement contains a properly formulated “interrogative subordinate clause.”

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=1912

Item three is also an unnecessary over-correction. As presented, the statement contains a properly formulated “interrogative subordinate clause.”

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=1912

take a closer look at that safire article. specifically, “Breaking a rule of style or even of civility gains force and meaning only when you know what code you are violating and why.” this is exactly what wallace was trying to teach us, as I’ve explained ad nauseum in the comments section. he was asking us to follow the code until we learned it. and, like it or not, both 1 and 3 represent errors in the code, if not in common usage.

take a closer look at that safire article. specifically, “Breaking a rule of style or even of civility gains force and meaning only when you know what code you are violating and why.” this is exactly what wallace was trying to teach us, as I’ve explained ad nauseum in the comments section. he was asking us to follow the code until we learned it. and, like it or not, both 1 and 3 represent errors in the code, if not in common usage.

I recognize both the right to this line of thinking and the dangers of arguing against it (so many writers are just bad!), but I prefer Russell Edson, who said:

“We are not interested in the usual literary definitions, for we have neither the scholarship nor the ear. We want to write free of debt or obligation to literary form or idea . . . there is more truth in the act of writing than in what is written.”

Perhaps I should put this comment underneath your comment about when people are authorized to claim poetic license. It doesn’t matter, I just wanted to put it somewhere to rebuff you confounding, arrogant scholars.

I recognize both the right to this line of thinking and the dangers of arguing against it (so many writers are just bad!), but I prefer Russell Edson, who said:

“We are not interested in the usual literary definitions, for we have neither the scholarship nor the ear. We want to write free of debt or obligation to literary form or idea . . . there is more truth in the act of writing than in what is written.”

Perhaps I should put this comment underneath your comment about when people are authorized to claim poetic license. It doesn’t matter, I just wanted to put it somewhere to rebuff you confounding, arrogant scholars.

[…] LINK […]

Thanks, that was fun. So:

1. So you say. Maybe this is a US/UK thing but I’ve never heard of that distinction in the UK. I’m prepared to be proved wrong (you’ll need numbers to do that) but this sounds like the artificial invention of a grammar-peeve, just like the oft-claimed distinction between refuting and rebutting.

2. The meaning was perfectly clear to me without cluttering the prose with a redundant preposition. The form you give is, to my ear, far worse writing than the original. Omit needless words, I suppose.

4. Your revised version is fine, but as a correction it’s a hypercorrection. The form you originally gave is in common usage and would almost certainly be unambiguous in context; although there are cases where placement matters (as the comments above suggest), in the majority it doesn’t. Your justification for the change suggests a bizarre sense that language is a sort of logical calculus. It ain’t.

5. The sentential adjectival phrase is clearly there as a caveat. It’s an evidential qualifier for what follows — it suggests to me that the understanding in question is a kind of subjective grip on the topic as opposed to objective expertise. Deleting it changes the sense of the whole sentence.

8. Get out of town. The split infinitive rule has never been consistently observed by good writers. Many modern grammarians, in any case, consider the “to” to be a stand-alone preposition rather than a part of the infinitive form of the verb.

9. It seems to me that “aggravating” is going through a semantic shift and many people now use it to mean “irritating”. This is not an error, it’s langauge change and whether it’s appropriate depends, like everything else, on the context and the audience. Again, I speak from a UK perspective, perhaps in the US this isn’t a widespread usage.

That we need to know “the code” in order to meaningfully break it is wrong. Those of us who don’t care about “the code” don’t care about the code. If you care about “the code” and I break it and it annoys (or even aggravates) you then it’s meaningful for you. Whether it was meaningful for me or not really doesn’t matter, does it?

Respecting the reader is one thing, but what if the reader you’re respecting is an elitist striving to find reasons to keep newcomers out of the club? What if, in other words, the code needs breaking?

R

Thanks, that was fun. So:

1. So you say. Maybe this is a US/UK thing but I’ve never heard of that distinction in the UK. I’m prepared to be proved wrong (you’ll need numbers to do that) but this sounds like the artificial invention of a grammar-peeve, just like the oft-claimed distinction between refuting and rebutting.

2. The meaning was perfectly clear to me without cluttering the prose with a redundant preposition. The form you give is, to my ear, far worse writing than the original. Omit needless words, I suppose.

4. Your revised version is fine, but as a correction it’s a hypercorrection. The form you originally gave is in common usage and would almost certainly be unambiguous in context; although there are cases where placement matters (as the comments above suggest), in the majority it doesn’t. Your justification for the change suggests a bizarre sense that language is a sort of logical calculus. It ain’t.

5. The sentential adjectival phrase is clearly there as a caveat. It’s an evidential qualifier for what follows — it suggests to me that the understanding in question is a kind of subjective grip on the topic as opposed to objective expertise. Deleting it changes the sense of the whole sentence.

8. Get out of town. The split infinitive rule has never been consistently observed by good writers. Many modern grammarians, in any case, consider the “to” to be a stand-alone preposition rather than a part of the infinitive form of the verb.

9. It seems to me that “aggravating” is going through a semantic shift and many people now use it to mean “irritating”. This is not an error, it’s langauge change and whether it’s appropriate depends, like everything else, on the context and the audience. Again, I speak from a UK perspective, perhaps in the US this isn’t a widespread usage.

That we need to know “the code” in order to meaningfully break it is wrong. Those of us who don’t care about “the code” don’t care about the code. If you care about “the code” and I break it and it annoys (or even aggravates) you then it’s meaningful for you. Whether it was meaningful for me or not really doesn’t matter, does it?

Respecting the reader is one thing, but what if the reader you’re respecting is an elitist striving to find reasons to keep newcomers out of the club? What if, in other words, the code needs breaking?

R

“That we need to know “the code” in order to meaningfully break it is wrong. Those of us who don’t care about “the code” don’t care about the code. If you care about “the code” and I break it and it annoys (or even aggravates) you then it’s meaningful for you. Whether it was meaningful for me or not really doesn’t matter, does it?”

It matters because your work will be judged by others, whether in a piece of fiction or a letter of intent or a job application or anything else. Wallace is teaching composition here. In the context of this class, teachers absolutely should teach people to write in a way that won’t cost them down the line. To say, “Oh don’t bother, most people will understand” is only going to potentially hurt your students down the road.

“That we need to know “the code” in order to meaningfully break it is wrong. Those of us who don’t care about “the code” don’t care about the code. If you care about “the code” and I break it and it annoys (or even aggravates) you then it’s meaningful for you. Whether it was meaningful for me or not really doesn’t matter, does it?”

It matters because your work will be judged by others, whether in a piece of fiction or a letter of intent or a job application or anything else. Wallace is teaching composition here. In the context of this class, teachers absolutely should teach people to write in a way that won’t cost them down the line. To say, “Oh don’t bother, most people will understand” is only going to potentially hurt your students down the road.

The above is great for poetry, not necessarily for professional writing (ie job applications or something).

The above is great for poetry, not necessarily for professional writing (ie job applications or something).

Lincoln — all true, but we’re slightly at cross purposes. My point was political: professionalization creates elites that have an interest in excluding others by setting up bars to entry. If we’re educators then we should let our students know that there exists a group of powerful idiots who think this stuff is important. What we shoudn’t do is tolerate for a moment the claim that they’re right simply because they’re powerful.

Part of this is also the professionalization of writing pedagogy. Teachers of writing have, after all, to have a body of expertise that can be passed on to students and tested in standardised examinations. This is the only way they can create a niche in the education system. To be fair to Wallace, I think he gets this, but his response it to throw up his hands and perpetuate it anyway.

We don’t send children to elocution lessons any more. Perhaps we’ll grow out of this, too, but only if we resist it.

Lincoln — all true, but we’re slightly at cross purposes. My point was political: professionalization creates elites that have an interest in excluding others by setting up bars to entry. If we’re educators then we should let our students know that there exists a group of powerful idiots who think this stuff is important. What we shoudn’t do is tolerate for a moment the claim that they’re right simply because they’re powerful.

Part of this is also the professionalization of writing pedagogy. Teachers of writing have, after all, to have a body of expertise that can be passed on to students and tested in standardised examinations. This is the only way they can create a niche in the education system. To be fair to Wallace, I think he gets this, but his response it to throw up his hands and perpetuate it anyway.

We don’t send children to elocution lessons any more. Perhaps we’ll grow out of this, too, but only if we resist it.

You should read Wallace’s essay in Harper’s that is linked above, as he deals (in my mind quite effectively) with with most of your criticisms.

You should read Wallace’s essay in Harper’s that is linked above, as he deals (in my mind quite effectively) with with most of your criticisms.

I also totally disagree that this stuff is merely random nonsense from the powerful elite. Some of these rules, like split infinitives, are fairly pointless and will soon be gone. But much of this stuff truly does affect meaning and/or risk confusing readers. Language only functions if we, whatever community of speakers, understands its rules and meanings. Encouraging some confused people to persist in, say, an incorrect definition of a word doesn’t seem to me like any useful political act.

This also may be a UK/US thing, but over here the prescriptivist like Wallace are in the minority in classrooms. Most teachers don’t teach grammar at all and throw up their hands saying “Oh, language can mean whatever I guess.”

I also totally disagree that this stuff is merely random nonsense from the powerful elite. Some of these rules, like split infinitives, are fairly pointless and will soon be gone. But much of this stuff truly does affect meaning and/or risk confusing readers. Language only functions if we, whatever community of speakers, understands its rules and meanings. Encouraging some confused people to persist in, say, an incorrect definition of a word doesn’t seem to me like any useful political act.

This also may be a UK/US thing, but over here the prescriptivist like Wallace are in the minority in classrooms. Most teachers don’t teach grammar at all and throw up their hands saying “Oh, language can mean whatever I guess.”

[…] Seemed like people enjoyed talking about the finer points of grammar and usage a month or so back, so I thought I’d provide a little morsel from a nonfiction workshop I took in college taught by someone who, among other accomplishments, was the most obsessively precise user of English I have ever and will ever encounter. I have, or, well, had, David Foster Wallace to thank for my own peevishness about mistakes in what he called S.W.E., or Standard Written English. So what follows is the complete text of a worksheet from his class. Whoever can come up with the most correct corrections will win something (currently taking prize suggestions/donations). I’ll post the answers once it seems as if nobody is trying anymore. Don’t worry if someone else posts their answers first; they may not be right! Not as easy as it may first look. All sentences have one crucial error in punctuation, usage, or grammar. Okay go! ANSWERS HERE when you’re ready […]

This is all nonsense. The key point of Orwell’s essay is that Effective Communication is all that ultimately matters. Old rules and antiquities to the wayside. Any postmodernist on the level of Wallace should know better.

This is all nonsense. The key point of Orwell’s essay is that Effective Communication is all that ultimately matters. Old rules and antiquities to the wayside. Any postmodernist on the level of Wallace should know better.

Lincoln — I agree that we have to teach the language, and in doing so we’re certainly teaching a normative system. I also agree that students — particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds — should have the opportunity to learn how to pass in higher-status society, linguistically and in other ways, if they wish to.

I do think, though, that there’s a big difference between mixing up “imply” and “infer” and insisting on “one another” for non-dual plural. It sounds like point-scoring: “Look at me! I know a rule you don’t!”. To score these points we have to keep inventing new rules, spurious as they may be. Huddleston & Pullum say flatly that empirical evidence “does not support this rule and there is not even any historical basis for it; most modern usage manuals recognise that the pronouns cannot be distinguished along these line” (p.1499, footnote).

I also agree to an extent that we should teach students to avoid misunderstandings. But it takes two to misunderstand, and I don’t think all the blame should in all cases be placed on the writer of non-standard English. yet this is exactly what happens when certain forms are presented as “correct” as opposed to merely “high status in certain contexts”.

My point isn’t as radical as I’ve led you to believe (sorry!) — it’s about how we frame what we teach, not that we teach it per se.

Lincoln — I agree that we have to teach the language, and in doing so we’re certainly teaching a normative system. I also agree that students — particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds — should have the opportunity to learn how to pass in higher-status society, linguistically and in other ways, if they wish to.

I do think, though, that there’s a big difference between mixing up “imply” and “infer” and insisting on “one another” for non-dual plural. It sounds like point-scoring: “Look at me! I know a rule you don’t!”. To score these points we have to keep inventing new rules, spurious as they may be. Huddleston & Pullum say flatly that empirical evidence “does not support this rule and there is not even any historical basis for it; most modern usage manuals recognise that the pronouns cannot be distinguished along these line” (p.1499, footnote).

I also agree to an extent that we should teach students to avoid misunderstandings. But it takes two to misunderstand, and I don’t think all the blame should in all cases be placed on the writer of non-standard English. yet this is exactly what happens when certain forms are presented as “correct” as opposed to merely “high status in certain contexts”.

My point isn’t as radical as I’ve led you to believe (sorry!) — it’s about how we frame what we teach, not that we teach it per se.

Amy —

Hey, I just realized that my comment signature on my work computer says ‘Muzzy,’ while my comment signature on my laptop says ‘Michael.’ I should fix that, hm? Same email address either way.

So anyway this is Michael (aka Muzzy) writing in to say thanks for the win. And I wouldn’t mind a copy of “Scorch Atlas” for my troubles, if it’s not too much to ask.

Amy —

Hey, I just realized that my comment signature on my work computer says ‘Muzzy,’ while my comment signature on my laptop says ‘Michael.’ I should fix that, hm? Same email address either way.

So anyway this is Michael (aka Muzzy) writing in to say thanks for the win. And I wouldn’t mind a copy of “Scorch Atlas” for my troubles, if it’s not too much to ask.

Grammar owned.

Grammar owned.

[…] See a strange post: HTMLGIANT / Abbreviation Challenge: Answers as well as Explanations […]

he certainly uses tired metaphors

i came into the room v. i came in the room

disagree.

disagree.

DFW was a wonderful writer, and one of the reasons why is that he broke every single one of these stupid, pigheaded “rules.”

Any linguist who has read Tense Present will tell you that Wallace was the worst kind of snoot, namely, the snoot-who-is-wrong, and this quiz is a perfect example of his pedantry.

DFW was a wonderful writer, and one of the reasons why is that he broke every single one of these stupid, pigheaded “rules.”

Any linguist who has read Tense Present will tell you that Wallace was the worst kind of snoot, namely, the snoot-who-is-wrong, and this quiz is a perfect example of his pedantry.

[…] You’d believe me if I said I scored five (1,4,5,6,9) correctly, wouldn’t you? Answers here. […]

“So, thanks to everyone who tried, but I think the winners are two early commenters, our own Ryan Call and the anonymous “Michael,” whoM I called David a few times.”

“So, thanks to everyone who tried, but I think the winners are two early commenters, our own Ryan Call and the anonymous “Michael,” whoM I called David a few times.”

Pss 121:1 KJV

I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.

Pss 121:1 KJV

I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.

DFW’s answer to number 6 is incorrect, and is in fact an example of the error claimed for number 7. Pleonastic ‘from’ (or ‘of’) has been used off and on for the past six hundred years. Or, to quote the OED:

c1430 Syr Tryam. 431 What do ye here, madam? Fro whens come ye?

1382 WYCLIF Matt. xxi. 25 Of whennes was the baptem of Joon; of heuene, or of men?

1590 SHAKES. Com. Err. III. i. 37 Let him walke from whence he came.

1731-8 SWIFT Pol. Conversat. Introd. 29 From whence I did then conclude..that Wine doth not inspire Politeness.

κτλ. Note that it shows up in prose, not just in verse for metrical reasons. Really, number 7 was a mistake. Once you admit arguing from idiom, you really can’t go around criticizing ancient phrases for being illogical.

DFW’s answer to number 6 is incorrect, and is in fact an example of the error claimed for number 7. Pleonastic ‘from’ (or ‘of’) has been used off and on for the past six hundred years. Or, to quote the OED:

c1430 Syr Tryam. 431 What do ye here, madam? Fro whens come ye?

1382 WYCLIF Matt. xxi. 25 Of whennes was the baptem of Joon; of heuene, or of men?

1590 SHAKES. Com. Err. III. i. 37 Let him walke from whence he came.

1731-8 SWIFT Pol. Conversat. Introd. 29 From whence I did then conclude..that Wine doth not inspire Politeness.

κτλ. Note that it shows up in prose, not just in verse for metrical reasons. Really, number 7 was a mistake. Once you admit arguing from idiom, you really can’t go around criticizing ancient phrases for being illogical.

[…] Take David Foster Wallace’s grammar challenge. Answers here. (via […]

I have to say, is it really needless repetition in #10? The sentence is conceivably clearer if “Christ” is repeated. What if “the Nephites” is a man? The Hebrides is a place, after all. For a reader who isn’t familiar with (a) the myth of Christ’s resurrection, or (b) the general guidelines for interpreting the gender/number of names like “the Nephites”, repeating “Christ” could be key in understanding the sentence.

I might suggest that there are millions of potential readers in this boat, e.g. Asians who speak good enough English to read that kind of sentence, but are not native speakers and are not familiar with Western mythology.

I have to say, is it really needless repetition in #10? The sentence is conceivably clearer if “Christ” is repeated. What if “the Nephites” is a man? The Hebrides is a place, after all. For a reader who isn’t familiar with (a) the myth of Christ’s resurrection, or (b) the general guidelines for interpreting the gender/number of names like “the Nephites”, repeating “Christ” could be key in understanding the sentence.

I might suggest that there are millions of potential readers in this boat, e.g. Asians who speak good enough English to read that kind of sentence, but are not native speakers and are not familiar with Western mythology.

Yeah, only #10 (avoid needless repetition) makes sense. In practice, sentences #2,3,4,8 and 9 are all correct English. In fact, the fixes for sentences #3,4 and 8 make the result worse. “Aggravating” comes from “aggraver” in French which does mean “make worse”, but so what? It is so commonly used to mean “irritating” that there’s no doubt about the meaning here. Plus, there’s nothing wrong with “whether or not”. Sure, it’s redundant, but that’s exactly why it’s used as an alternative to “if”: to make it long and hard to miss. The obvious agenda here is to sermonize against the way people usually speak to somehow feel superior over them, rather than to actually improve communication, using fake logics-inspired arguments taken from God knows where. The fix to “from whence” should be “from where”, not “whence”, since that eliminates a weird word nobody uses. Nobody cares about your bizarre sentence re-orderings to avoid split infinitives in “She didn’t seem ever to stop talking.”, put the adverb where it’s expected and easiest to understand.

Remember: if everybody says it, then it’s correct English, no matter what a grammar or a dictionary says.

Yeah, only #10 (avoid needless repetition) makes sense. In practice, sentences #2,3,4,8 and 9 are all correct English. In fact, the fixes for sentences #3,4 and 8 make the result worse. “Aggravating” comes from “aggraver” in French which does mean “make worse”, but so what? It is so commonly used to mean “irritating” that there’s no doubt about the meaning here. Plus, there’s nothing wrong with “whether or not”. Sure, it’s redundant, but that’s exactly why it’s used as an alternative to “if”: to make it long and hard to miss. The obvious agenda here is to sermonize against the way people usually speak to somehow feel superior over them, rather than to actually improve communication, using fake logics-inspired arguments taken from God knows where. The fix to “from whence” should be “from where”, not “whence”, since that eliminates a weird word nobody uses. Nobody cares about your bizarre sentence re-orderings to avoid split infinitives in “She didn’t seem ever to stop talking.”, put the adverb where it’s expected and easiest to understand.

Remember: if everybody says it, then it’s correct English, no matter what a grammar or a dictionary says.

Ah, now I checked the answers after my own attempts, and I think you and DFW are wrong about 10. First off, “His” could refer to Mormon’s resurrection just as easily as to Christ’s.

More important, while it’s true that the repetition of “Christ” is somewhat awkward, it has some rhetorical force here. “Christ’s resurrection” refers to a generally held belief among Christians. “Christ’s ministry” is peculiar to Mormonism. So “Christ’s resurrection” points to an already well defined public event. To turn that into “his resurrection” subordinates the more general Christian Christ to the Mormon Christ. Corrected that way, the sentence makes the Mormon Christ’s actions and experiences the subject of the inquiry, and those actions and experiences include the NT account of his resurrection. As originally couched, the Mormon Christ is said to do something after the events that the second part of the sentence reminds us of, which are part of the NT.

Ah, now I checked the answers after my own attempts, and I think you and DFW are wrong about 10. First off, “His” could refer to Mormon’s resurrection just as easily as to Christ’s.

More important, while it’s true that the repetition of “Christ” is somewhat awkward, it has some rhetorical force here. “Christ’s resurrection” refers to a generally held belief among Christians. “Christ’s ministry” is peculiar to Mormonism. So “Christ’s resurrection” points to an already well defined public event. To turn that into “his resurrection” subordinates the more general Christian Christ to the Mormon Christ. Corrected that way, the sentence makes the Mormon Christ’s actions and experiences the subject of the inquiry, and those actions and experiences include the NT account of his resurrection. As originally couched, the Mormon Christ is said to do something after the events that the second part of the sentence reminds us of, which are part of the NT.

She didn’t ever seem to stop talking.

She didn’t ever seem to stop talking.

That was the solution I came to as well.

That was the solution I came to as well.

And there are still errors in the ‘corrected’ sentences … medice, cura teipsum!

5) “In my own mind, I can understand why its implications may be somewhat threatening”

Granted, DFW fixed the above to eliminate “in my own mind”, but the real problem in the original sentence is that “its” only has one noun to refer back to – “mind” – meaning that this sentence really says “In my own mind, I can understand why my mind’s implications may be somewhat threatening”. The corrected sentence has an ambiguous pronoun (what is “it”?), so the grammar is still problematic.

7) “all religions are unfounded”

This isn’t the best adjective. Religions can’t be unfounded – somebody has to inaugurate them – though their creeds can be.

10) “Christ’s ministry to the Nephites, which allegedly took place”

‘Which’ here introduces a relative clause, which has to be next to the noun that it modifies, as in this sentence (the second ‘which’ describes ‘a relative clause’). So sentence 10 says that ‘the Nephites allegedly took place’. (This sort of error is frequently tested on the SAT and GMAT.) One correction might be “Christ’s ministry to the Nephites, a sermon which allegedly took place”.

And there are still errors in the ‘corrected’ sentences … medice, cura teipsum!

5) “In my own mind, I can understand why its implications may be somewhat threatening”

Granted, DFW fixed the above to eliminate “in my own mind”, but the real problem in the original sentence is that “its” only has one noun to refer back to – “mind” – meaning that this sentence really says “In my own mind, I can understand why my mind’s implications may be somewhat threatening”. The corrected sentence has an ambiguous pronoun (what is “it”?), so the grammar is still problematic.

7) “all religions are unfounded”

This isn’t the best adjective. Religions can’t be unfounded – somebody has to inaugurate them – though their creeds can be.

10) “Christ’s ministry to the Nephites, which allegedly took place”

‘Which’ here introduces a relative clause, which has to be next to the noun that it modifies, as in this sentence (the second ‘which’ describes ‘a relative clause’). So sentence 10 says that ‘the Nephites allegedly took place’. (This sort of error is frequently tested on the SAT and GMAT.) One correction might be “Christ’s ministry to the Nephites, a sermon which allegedly took place”.

I have great respect for David Foster Wallace. This quiz, however, is a perfect example of why so many people roll their eyes when the issue of “good grammar” comes up. Most of the supposed errors in the quiz have nothing to do with grammar and are not necessarily errors. They are, at best, usage hiccups or compositional missteps.

BTW — there really is a grammatical error in the OP — it should read (IIRC), “I have ever *encountered* and ever will encounter.”

OK, end of rant.

I have great respect for David Foster Wallace. This quiz, however, is a perfect example of why so many people roll their eyes when the issue of “good grammar” comes up. Most of the supposed errors in the quiz have nothing to do with grammar and are not necessarily errors. They are, at best, usage hiccups or compositional missteps.

BTW — there really is a grammatical error in the OP — it should read (IIRC), “I have ever *encountered* and ever will encounter.”

OK, end of rant.

I am skeptical of the correction of #10 because I recall that it is improper to use a possessive pronoun (“his”) when the antecedent does not appear in the sentence. “Christ’s” is not the antecedent because an antecedent must be a noun. The antecedent for “his” is “Christ,” which does not appear in the sentence as a noun.

Did anyone else learn that rule?

I am skeptical of the correction of #10 because I recall that it is improper to use a possessive pronoun (“his”) when the antecedent does not appear in the sentence. “Christ’s” is not the antecedent because an antecedent must be a noun. The antecedent for “his” is “Christ,” which does not appear in the sentence as a noun.

Did anyone else learn that rule?

I think you meant to say, “Orwell’s essay on language is one of my all-time favorite things.”

Saying “one of my” can’t also mean “absolute.” Ironically, Orwell’s essay argues that if you can cut a phrase or sentence shorter, you should.

I think you meant to say, “Orwell’s essay on language is one of my all-time favorite things.”

Saying “one of my” can’t also mean “absolute.” Ironically, Orwell’s essay argues that if you can cut a phrase or sentence shorter, you should.

couldn’t you have an absolute favorite essay, an absolute favorite poem, and an absolute favorite pair of earrings and refer to any one of them as one of your absolute favorite things?

couldn’t you have an absolute favorite essay, an absolute favorite poem, and an absolute favorite pair of earrings and refer to any one of them as one of your absolute favorite things?

In your explanation of item #9, you state:

“Aggravating was a special peeve of Wallace’s…”

This is incorrect usage of the apostrophe. It should read either “peeve of Wallace” or “Wallace’s peeve.”

In your explanation of item #9, you state:

“Aggravating was a special peeve of Wallace’s…”

This is incorrect usage of the apostrophe. It should read either “peeve of Wallace” or “Wallace’s peeve.”

DFW was simply a product of the Strunk & White generation. People do English much much better than they describe its workings and the S&W crowd are living testament to that fact.

He is yet another author that illustrates that people can write without knowing much of anything about how the English language works.

The problem with DFW was that he placed too much faith in his mother’s nonsense. Why he failed to use all the much vaunted “ab[ility] to ingest complex mathematics, logic and philosophy”, we’ll never know.

DFW was simply a product of the Strunk & White generation. People do English much much better than they describe its workings and the S&W crowd are living testament to that fact.

He is yet another author that illustrates that people can write without knowing much of anything about how the English language works.

The problem with DFW was that he placed too much faith in his mother’s nonsense. Why he failed to use all the much vaunted “ab[ility] to ingest complex mathematics, logic and philosophy”, we’ll never know.

I looked over the “answers” one more time. Good Lord!

How many of these phrenologists are still teaching English grammar courses in American colleges and universities?

I looked over the “answers” one more time. Good Lord!

How many of these phrenologists are still teaching English grammar courses in American colleges and universities?

are we making a ‘most ignorant comments of 2009’ list? cuz this just made mine.

are we making a ‘most ignorant comments of 2009’ list? cuz this just made mine.

She never seemed to stop talking?

She never seemed to stop talking?

concurred.

concurred.

#1

M-W

usage Some handbooks and textbooks recommend that each other be restricted to reference to two and one another to reference to three or more. The distinction, while neat, is not observed in actual usage. Each other and one another are used interchangeably by good writers and have been since at least the 16th century.

The real ‘boner’ was made by DFW.

It’d be interesting to hear the reasons behind this prescription.

#3

M-W

1 a : in the event that b : allowing that c : on the assumption that d : on condition that

2 : whether

The problem is that you as students sit doe-eyed sucking in all this nonsense when the proof refuting it is all around you. Before you try to make DFW out as some grammar guru, look carefully at how badly he has analysed language.

‘if’ has a number of meanings [see the M-W entry above]. ‘if’ has a direct entry, 2., showing us that sometimes the meaning of ‘if’ and ‘whether’ are synonymous.

Again, it has to be asked, why would someone with as good a head as DFW not look past the simplistic nonsense found in usage manuals?

#1

M-W

usage Some handbooks and textbooks recommend that each other be restricted to reference to two and one another to reference to three or more. The distinction, while neat, is not observed in actual usage. Each other and one another are used interchangeably by good writers and have been since at least the 16th century.

The real ‘boner’ was made by DFW.

It’d be interesting to hear the reasons behind this prescription.

#3

M-W

1 a : in the event that b : allowing that c : on the assumption that d : on condition that

2 : whether

The problem is that you as students sit doe-eyed sucking in all this nonsense when the proof refuting it is all around you. Before you try to make DFW out as some grammar guru, look carefully at how badly he has analysed language.

‘if’ has a number of meanings [see the M-W entry above]. ‘if’ has a direct entry, 2., showing us that sometimes the meaning of ‘if’ and ‘whether’ are synonymous.

Again, it has to be asked, why would someone with as good a head as DFW not look past the simplistic nonsense found in usage manuals?

Shouldn’t there be an apostrophe in ‘its’ in the 5th one?

Shouldn’t there be an apostrophe in ‘its’ in the 5th one?

[…] goodness, she also posted the answers. This inspired me to pick up a copy of Modern American Usage to keep under my pillow at […]

[…] 2) Amy McDaniel, a former student of Wallace’s, posted a grammar challenge at htmlgiant that Wallace had used in class. You can read the answers here. […]

[…] For example, what’s wrong with this sentence: “I only spent six weeks in Napa.” Can you spot it? It’s subtle, and I didn’t get it. But it sounds obvious to my ear once I read the answers, which you can find here, along with explanations. […]

[…] of “aggravating” when one means “irritating.” As McDaniel mentions in her followup on the quiz answers, and her second followup explanation, DFW was obsessively concerned over clarity in […]

[…] Amy McDaniel of HTMLGIANT posted a grammar challenge. A grammar challenge taken from a college course worksheet written and taught by the late David Foster Wallace. Test yourself without the answers or just read through the questions and answers here. […]

booyah

booyah

[…] (or, rather, 20,249 people in the world) decided they wanted in on the DFW Grammar Challenge (part 2, part 3). So what was it that brought the teeming hordes over our way? Was it Jeremy […]

I’ve enjoyed the ensuing banter much more than the grammar challenge. Thank you all!

I’ve enjoyed the ensuing banter much more than the grammar challenge. Thank you all!

Well, i wish they would have made languages a bit simpler, i struggle learning my 4th languages, the grammer is always the problem (:

Well, i wish they would have made languages a bit simpler, i struggle learning my 4th languages, the grammer is always the problem (:

Really interesting post! English is such a complex and, in reality, illogical language. It’s always a challenge for a non-native speak such as myself!

Great article, as a linguistics student I really enjoyed that! Thx!

Really interesting post! English is such a complex and, in reality, illogical language. It’s always a challenge for a non-native speak such as myself!

Great article, as a linguistics student I really enjoyed that! Thx!

I took a facebook quiz that said I wrote like David Foster Wallace. I was at the time unfamiliar with his work. Now the more I read about him the more I feel cheated at never having had a chance to hang with him … ;-) We sound like intellectual twins separated at birth!

I took a silly online quiz that said David Foster Wallace was the author whose writing mine most closely resembled. I was at the time unfamiliar with his work. Now the more I read his work and about him, the more I feel cheated at never having had a chance to loiter about Flora’s or Kaldi’s with him. We sound like intellectual twins separated at birth!

[…] I re-stumbled upon an old grammar worksheet from David Foster Wallace in which he had his students try to correct sentences that largely […]