“DEAD DEAD,” Quraysh Ali Lansana

DEAD DEAD

heat on the southside

I.

last night, police cordoned the four square

blocks surrounding my house in pursuit of a thug

who unloaded on the shell of a gangsta

in the funeral parlor filled with formaldehyde

and lead. black folks scattered, staining

complicated streets. i settle in for summer:

the maze to the front door, running teens

smelling of weed and tragedy from my stoop

reminding my sons they are not sources

of admiration, praying that might change. not yet

june heat rises like the murder rate, gleam

and pop already midnight’s bitter tune

II.

fifteen years ago, tyehimba jess

told me about a funeral home

with a drive through window.

you pull up, push a call button

through bulletproof glass a friendly

somber attendant takes your request.

First Sentences or Paragraphs #5: Best European Fiction 2010 Edition

[series note: This post is the fifth of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

“Albania is a country where no one ever dies.”

– from The Country Where No One Ever Dies, Ornela Vorpsi

“If I had urinated immediately after breakfast, the mob would never have burnt down the orphanage.”

– “The Orphan and the Mob,” Julian Gough

“A cousin of mine had an aquarium built on her terrace, a rather imposing tank where strange, exotic sea creatures amused themselves in the company of all sorts of local specimen, destined to be eaten.”

– from While Sleeping, Antonio Fian READ MORE >

The xerox machine: printing press of the people

Karen Lillis is currently serializing a memoir about working at St. Mark’s Bookshop called Bagging The Beats At Midnight: Confessions of an Indie Bookstore Clerk over at Undie Press. Her recent installment, titled “People Who Led Me to Self-Publishing,” discusses the inspiring and energetic figures she encountered, people who took artistic matters into their own hands by making sloppy, lo-fi xeroxed booklets that were sold on a special consignment rack at St. Mark’s. Karen reminds us that writers such as Anais Nin, William Blake, Walt Whitman, Kathy Acker, Gertrude Stein, and others all self-published at one point. There’s a certain magic about it—the immediacy of it, the openness, the way any wing nut or fanatic or obsessive outsider can be given an equal hearing on the consignment rack. No filtration or editorial process—just print, copy, distribute.

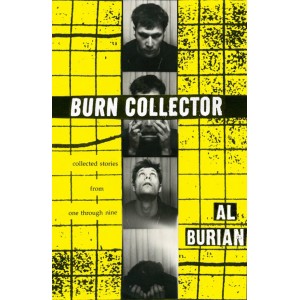

In a recent email I sent to Al Burian, I wrote that I was interested in bridging the gap between the small press/indie publishing world and the self-publishing/zine world. Al is kind of a cult figure in the self-publishing world, but is probably virtually unknown to small press and indie lit readers (although he did get some kind of honorable mention in The Best American Nonrequired Reading series one year). I’ve been reading his zines since I was 13 and I’m still totally obsessed with them. Since Al Burian was my favorite zine writer, over the years I let everyone I knew borrow his writings—teachers, friends, family. Some instantly became obsessive fans of his work as well. Since last month Al’s out-of-print collection of early zines, titled Burn Collector, is finally back in print after being republished by PM Press. (You should check it out—I’ve probably read it more times than any other book in my life.) Al’s zine Burn Collector and others like his inspired me to start self-publishing when I was 15.

In a recent email I sent to Al Burian, I wrote that I was interested in bridging the gap between the small press/indie publishing world and the self-publishing/zine world. Al is kind of a cult figure in the self-publishing world, but is probably virtually unknown to small press and indie lit readers (although he did get some kind of honorable mention in The Best American Nonrequired Reading series one year). I’ve been reading his zines since I was 13 and I’m still totally obsessed with them. Since Al Burian was my favorite zine writer, over the years I let everyone I knew borrow his writings—teachers, friends, family. Some instantly became obsessive fans of his work as well. Since last month Al’s out-of-print collection of early zines, titled Burn Collector, is finally back in print after being republished by PM Press. (You should check it out—I’ve probably read it more times than any other book in my life.) Al’s zine Burn Collector and others like his inspired me to start self-publishing when I was 15.

What is Experimental Literature? {pt. 2}

Settle thy studies, Faustus, and begin

To sound the depth of that thou wilt profess:

Having commenc’d, be a divine in shew,

Yet level at the end of every art,

And live and die in Aristotle’s works.— Christopher Marlowe, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (1604)

One way to think about experimental literature would be to consider it in relation to conventional literature. Which begs the question: what is conventional literature? The answer to that question is much easier than the answer to the titular question of this post. The answer is this: conventional literature is that which follows Aristotelian prescription. Plain and simple. So if you want to know what experimental literature is, you might begin by considering it to be that which deviates from Aristotelian prescription.

Brian Evenson illuminates the problem of Aristotle’s suffocating influence in this great essay called “Notes on Fiction and Philosophy” in this amazing collection of literary criticism called Fiction’s Present: Situating Contemporary Narrative Innovation (SUNY Press, 2008), at the beginning of which he suggests:

[T]o move to an understanding of late twentieth- early twenty-first-century fiction, the first step is to move out of the fourth century BC: to let go of the Aristotelian notions that still dominate most thinking about fiction in writing workshops today…Discussions of setting, plot, character, theme, and so on, their parameters derived from Aristotle, seem hardly to have advanced beyond New Criticism’s neo-Aristotelianism; and when a workshop student says “I didn’t find the character believable,” usually the model for believability is firmly entrenched in nineteenth-century notions of consistency that have probably less to do with how real twenty-first century people act (not to mention nineteenth-century people) than with specific, and often dated, literary conventions.

I’d like to use this quote from Evenson as my jumping off point.

“There Are Three Dead People In Me”

Emily Kendal Frey is a poet I like. She lives in Portland, Oregon and teaches at Portland Community College. She is the author three chapbooks: Airport (Blue Hour 2009), Frances (Poor Claudia 2010), and The New Planet (Mindmade Books 2010). A full-length collection, The Grief Performance, was selected by Rae Armantrout for the 2010 Cleveland State University First Book Prize, and is forthcoming in the spring of 2011. A new series, Sorrow Arrow, appears in regular installments at Ink Node.

Here is a new poem, [A HISTORY OF KNIVES]:

When I met you we were the shape of salt shakers. I married my dad and threw him in the ocean. I dragged him along the bottom as he filled with salt. I opened my legs and a grasshopper was there. Your first home was a house on stilts with butter dishes READ MORE >

RACCOONS

Tonight I was at the house of a friend whose house I’d never been to before and there was a noise in the back yard, and my friend said, “Want to meet the raccoons?” So we went to the back yard.

READ MORE >

First Sentences or Paragraphs #4: Norton Anthology of Short Fiction A-G Edition

[series note: This post is the fourth of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

“The slaughter hasn’t started yet.”

– Lee K. Abbott, “One of Star Wars, One of Doom”

“That was the year Hunca Bubba changed his name.”

– Toni Cade Bambara, “Gorilla, My Love”

“What he first noticed about Detroit and therefore America was the smell.”

– Charles Baxter, “The Disappeared”

“Alberto Perera, librarian, granted no credibility to police profiles of dangerous persons.”

– Gina Berriault, “Who Is It Can Tell Me Who I Am?”

“A man stood upon a railroad bridge in Northern Alabama, looking down into swift waters twenty feet below.”

– Ambrose Bierce, “An Occurence at Owl Creek Bridge”

“The visible work left by this novelist is easily and briefly enumerated.”

– Jorge Luis Borges, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” READ MORE >

2 things i’m wondering

1. I met with a student to give advice on his MFA sample writing portfolio. Since I read these portfolios for my university and wrote one for my MFA, I felt ‘qualified,’ but with Tao Lin quotation marks. Some of the student’s poems had images and word-play. Tropes. Alliteration, at least one spondee. The first page was strong. I told him, “Good. You showed on the first page that you have read poetry and care some about words. The first page is important. Thoughts are being made.” I said, “You have images immediately. A lot of people sending in won’t have any images. They won’t get in. A lot of people like to write poetry, not poems. I mean they write about pride or love…” (trailing off. not quite sure what I meant here)

Content: The poems were about hangovers, beer, marijuana. I said, “These are sort of derivative ‘beat’ poems. That’s OK, write what you want once you’re in graduate school, but I think you should play the game a little. Get in grad school first.” I told him many readers would groan when they read poems about hangovers, beer, marijuana. “People are going to think you read some Bukowski. They’ll think you’re a type.” The phone rang 4 times and I ignored it. I said, “Do you have poems about any others things?” He did. Put some of those poems in the sample, I advised. I said again, “This isn’t a criticism of your work. Any subject is fine. Write what you want. I’m just trying to help you get into grad school.”

First Sentences or Paragraphs #3: Philip Roth Edition

[series note: This post is the third of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

The first time I saw Brenda she asked me to hold her glasses.

– Goodbye, Columbus

Dear Gabe, The drugs help me bend my fingers around a pen. READ MORE >

Iambik Audiobooks: Lish, Tillman, Hunt, etc.

Iambik Audiobooks is a new publisher of audio editions of curated literary fiction. Their current roster includes Gordon Lish, Lynne Tillman, J. Robert Lennon, Laird Hunt, Lydia Millet, and several others, all priced at a very reasonable $4.99 for the majority of their titles.

I picked up the 18 hour compendium of Lish reading selections from his recent Collected Fictions. The recording is pristine, and includes often introductions or lead ins by Lish. It’s the first time he’s ever read his own work aloud for the public. Because the hefty length, this one is the most expensive at the site, but still only $9.99 for the whole set, and also available in smaller editions for a lower price. Hearing him read the work himself adds a whole other layer to the fold. You can preview it here [EDIT: the preview is not of Lish himself; some of the works are read by Gregg Margarite]. I feel like I’ll be listening to this again and again over the years. Maybe I’ll drive somewhere, and now I don’t have to buy like Clive Barker.

Really excited to see such an excellently executed version of a great idea. Check them out.