Craft Notes

I am drinking gin & wrote about 18 long titles i randomly chose using wikipedia

If the New Sincerity is anything real or coherent (and I wrote that post last Monday because I, like others, am trying to figure out whether that’s so, or will be so), then we should be able to identify the devices or moves that define it—that arguably make a piece read as being “New Sincere.” The “New” implies they produce that sincere effect right now, in the current literary landscape; whether the techniques or devices are entirely new doesn’t matter (they could be older techniques, fallen out of prominence, now returned). Similarly, it’s irrelevant whether the author using them is “really” being sincere. What matters instead is that

If the New Sincerity is anything real or coherent (and I wrote that post last Monday because I, like others, am trying to figure out whether that’s so, or will be so), then we should be able to identify the devices or moves that define it—that arguably make a piece read as being “New Sincere.” The “New” implies they produce that sincere effect right now, in the current literary landscape; whether the techniques or devices are entirely new doesn’t matter (they could be older techniques, fallen out of prominence, now returned). Similarly, it’s irrelevant whether the author using them is “really” being sincere. What matters instead is that

- Those devices exist;

- People think they “feel sincere” (as opposed to other devices, which don’t);

- “Being sincere” has some value at the present moment.

Why sincerity? What is its present value? My broad and still developing belief is that “sincere” writing is one means of breaking with the aesthetics of postmodernism and self-referentiality: invocation of Continental Theory, metatextuality, excessive cleverness, hyper-allusion, &c. What makes writing “sincerely” even more delicious when perceived against postmodernism 1960–2000 is that it proposes to offer precisely what pomo said didn’t matter or couldn’t exist: direct communion with another coherent, expressive self, even truth by means of language. (Don’t tell Chris Higgs!)

One of my first impressions of the NS came when I started noticing artists and authors using longer titles—in particular, long rambly ones with strong emotional resonances. My thought then and I think now was that both the length and the ramble, as well as the emotive quality, signaled non-mediation: a desire to appear uncensored, unrevised. Those titles stood out (defamiliarized the title) because they failed to comply with what a “proper,” “edited,” “thoughtful” title should be.

Is this a sensible thing to argue? Have I had too many G&Ts? Let’s pursue …

So I’ve gathered a bunch of long titles (in reverse chronological order) but this isn’t any definitive list. And I’m not drinking gin (I love lying) but I am writing fairly extemporaneously, recording my thoughts in a semi-casual manner. Like I said, I’m still trying to figure all this out, and will appreciate hearing your thoughts (and other long titles!) by way of Facebook / Twitter / in the comments section.

I also wish to make crystal clear that

- I don’t think that all long rambly titles are New Sincerist, or are affixed to NS works;

- I don’t think that New Sincerist works have to have long rambly titles;

- Rather, I think that a certain kind of long rambly title is one thing a New Sincerist work can do—it is one current strategy among many for communicating “sincerity.”

In fact, as we’ll see, the titles that I think are New Sincere are accomplishing that in diverse ways—projecting sincerity from different angles. (And we’re talking only titles here, not the books themselves.)

selected unpublished blog posts of a mexican panda express employee (2011, Megan Boyle, Muumuu House)

This is very specific, but there’s also a certain preciousness at work—a naivety that “unpublished blog posts” (selected ones, even) of someone working in the service industry is worthy of said specificity. Is it therefore ironic? I wouldn’t call that ironic myself; I think naive or precious is better. (Other than the “Mexican” part, the book appears to be what its title claims—leaving us to wonder how to read that word—literally? metaphorically?—and even whether it modifies “employee” or “panda express.”) Is it “sincere”? … Perhaps? There’s a confessional quality to it that matches the book’s contents—pieces like “everyone i’ve had sex with,” “i am kind of a disgusting person,” and “i want to fall in love or something” (those titles strike me as very NS). Note also the use of all lowercase.

When All Our Days Are Numbered Marching Bands Will Fill the Streets & We Will Not Hear Them Because We Will Be Upstairs in the Clouds (2010, Sasha Fletcher, Mudluscious Press)

This title is more exuberant, carrying a triumphant, emotional tone. It also has a certain preciousness, too. It’s most definitely not ironic. Is it sincere? Yeah, I think so—emotional exuberance (getting carried away) is one way of being genuine (you lose yourself in your unmediated emotions). This title also reminds me of Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, certainly a nakedly emotional / sincere-sounding album.

during my nervous breakdown i want to have a biographer present (2009, Brandon Scott Gorrell, Muumuu House)

This title is a good example of how the ironic/sincere angle is a dead end. Is this a sincere statement, or an ironic one? I can’t tell from just the title alone (I haven’t read the book). It does seem clever in a way none of the other titles have been so far. But note how it is saying that it is during the author’s nervous breakdown that the biographer should be present—i.e., an uncontrollably emotive period of the author’s life is what should be recorded (documented, even) in/as literature. + the lowercases

sometimes my heart pushes my ribs (2009, Ellen Kennedy, Muumuu House)

This is, I’d argue, classic New Sincerity. There’s the qualifier “sometimes,” and the whole tone of the title is unguarded, emotive, sincere. I don’t get the sense that the title is being used in any ironic or kitsch way; there’s a genuine embrace of this way of being. For the heart to push the rubs, the heart must be beating very hard, or be very swollen—extreme emotion. + more the lowercases (a definite muumuu h thing)

This Is It and I Am It and You Are It and So Is That and He Is It and She Is It and It Is It and That Is That (2008, Marnie Stern)

Now we’re at an album title. There’s a mania we haven’t yet seen, but also an overt rhythmic pattern. (The title matches well the way that Marnie Stern plays.) So the mania is harnessed by—overridden and controlled by, even—a metrical form. Is it ironic? No. Is it “sincere”? No, I don’t think so. It’s abstract, geometrical.

Brief Weather & I Guess a Sort of Vision (2007, Anthony Robinson, Pilot Books)

Robinson’s an actual New Sincerist! So his title has to qualify, right? Two things that leap right out are the ampersand and the “I Guess a Sort of,” which conveys a very casual, confessional, unrevised tone—an uncertainty that Robinson is willing to confess to. It’s hubris—an unwillingness to call his vision a Vision.

No One Belongs Here More Than You (2007, Miranda July, Scribner)

Miranda July is New Sincere, I’d argue, because her work continuously promises direct communication with an extremely emotive person—a little girl playing dress up make believe. July is also precious and Twee and many other things as well, yes, but I’d argue that a large part of her appeal is the promise of direct, raw emotion, which is often presented through the promise that July is speaking directly to you and no one else (which this title of course does). This emotional force was a large part of what attracted me to her work when I first encountered it in the late 1990s: she was emotionally intense in a way I saw few other literary artists being. She gave the impression of being completely out of control—and of course she must have worked very hard indeed to craft precisely that impression.

you are a little bit happier than i am (2006, Tao Lin, Action Books)

Like in the July title, there’s the sense Lin is speaking directly to you, no one else. The sole topic of conversation of course is our relative emotional states. Note the imprecision of the “little bit.”

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006, Sacha Baron Cohen & Larry Charles)

The effect here is one of mistranslation—the wacky way non-native speakers speak! Both the the title and the film are satirical, put-ons. I’m going to call ironic. This is one of the kinds of things that the New Sincerity is not, and is defining itself against.

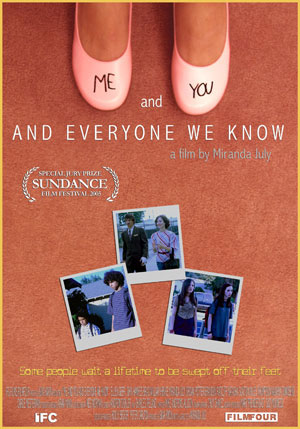

Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005, Miranda July)

Again, there’s that direct address, that promise of special inclusion. A shared personal space you can enter into. The conjunctions also create a breathless effect; July’s work is often breathless (literally!).

Looking Is Better Than Feeling You (2002, Astria Suparak)

Astria’s a friend of mine and a friend of July’s and it was in her festival programs that I first encountered this kind of title. At the time I thought it sounded “very art school” and “very hip” (Astria was then attending the Pratt Institute). It’s precious and Twee, perhaps, but that also doesn’t rule out it possibly being New Sincerist. (I think of Twee/preciousness and the New Childishness and the New Sincerity as being fellow travelers, aesthetic strategies very capable of enabling one another even while they have their own salient qualities.) (If I get any drunker, I might even try to argue/suggest that they collectively form a kind of neo-romanticism.) This title seems confessional and even addressed to a lover; it’s also kind of diminutive / shy. I’d lump it in with a broad New Sincere aesthetic, leaning toward the precious art school side. (Jimmy Chen, I need you to make a matrix.)

Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas to Heaven (2000, Godspeed You! Black Emperor)

This is not unlike Fletcher’s title, above; the effect is exuberant, triumphant. (Lifting your fists is anthemic.) We have direct address again, and of a very specific kind—the speaker somehow knows that I am a weakling. Perhaps I’m young? That kind of exuberance would fit with my being prepubescent and constantly at risk of being blown away by the world. The suggestion here (phrased as a command or challenge—an invocation) is that performing this anthemic gesture will enable me to receive a divine transmission. So while it’s certainly precious, I’m not registering any irony whatsoever. GY!BE means to deliver on their promise.

A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again (1997, David Foster Wallace, Little, Brown and Co.)

Note the emphasis on I, not you. There’s a confessional quality, but it’s a very guarded vulnerability: fool me once, shame on me, but also note how cleverly I can recover. That cleverness defines all or most of Wallace’s writing, which always feels hyper-articulate and thought out, as opposed to, say, Lin’s quieter, less guarded title above.

This Is a Long Drive for Someone with Nothing to Think About (1996, Modest Mouse)

This title is for someone, but not necessarily for you. So its intimacy is blunted. There’s a diminutive and confessional quality, and I don’t think Isaac Brock is being ironic. But what’s lacking, perhaps, is some of the more emotionally intense/exuberant/intimate/confessional qualities the New Sincerists would pick up on and amplify…? Styles come from places, after all—techniques develop when people refine what others have done, bringing out sharper/other qualities.

The Incredibly True Adventure of Two Girls in Love (1995, Maria Maggenti)

This is a calculatedly ironic title. The point is that lesbianism in 1995 had to be presented as something extraordinary or spectacular (because it was shocking!) when it was “truly” an ordinary thing. The everyday second half of the title (“Two Girls in Love”) completely undercuts the spectacular nature of the first half.

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984, W. D. Richter)

This title works differently than the one immediately above. It’s similarly spectacular, but it’s spectacular all the way through. It’s genuine about what it’s selling, and has a silly/childish/comic quality to it. It’s not ironic (nor is the film). But, despite the fact that it inspired Wes Anderson, it lacks the preciousness we’d associate with Twee / the New Childishness / the New Sincerity—and it’s not at all intimate, or revealing/confessing anything.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981, Raymond Carver, Knopf)

The we promises intimacy and there’s a focus on emotion. There’s also a sense that we’re going to really get at something we usually avoid even when talking about something as intimate as love. It’s not New Sincerist, but I think we can see one possible origin for the aesthetic. (Dirty realism seems a definite influence on Lin if no one else.)

Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? (1976, Raymond Carver, McGraw-Hill)

The effect of repeating the please is to imply that the speaker is speaking purely emotionally—unguardedly. It’s also addressed to a you that the speaker is having an argument with. Notice though that Carver always feels very grown up in comparison to NS stuff; it’s always adults who are doing the speaking (and not young adults). There are appreciable differences between the New Childishness and the New Sincerity (Dorothea Lasky, for instance, is NS bbut not I think NC), but they hold hands in many places (hold many hands?).

The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum at Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (1963, Peter Weiss)

This is hyper-specificity, hyper-precision. It’s not ironic and it’s not sincere; it’s purely literal, to the point of anal retention / obsessiveness. Almost bureaucratic—which makes sense, given the work’s interest in juxtaposing control with the controlled, and madness with reason.

…

now you & i and our cat will grow older and die, but come dawn we will float through boulevards made kaleidoscopic with our blood to reunite as ghosts in the comments, i sometimes allow myself to think.

Tags: Astria Suparak, blake butler, Buckaroo Bonzai, david foster wallace, elisa gabbert, Ellen Kennedy, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Larry Charles, Maria Maggenti, Marnie Stern, megan boyle, Miranda July, Modest Mouse, Mudluscious Press, muumuu house, New Sincerity, Peter Weiss, raymond carver, Sacha Baron Cohen, Sasha Fletcher, Tao Lin, Twee

I think you’re going to have to better articulate what you mean by “sincere,” because the way you’re using the word doesn’t jibe with the dictionary:

1. Free from pretense or deceit; proceeding from genuine feelings.

2. (of a person) Saying what they genuinely feel or believe; not dishonest or hypocritical.

So when you say, “it’s irrelevant whether the author using them is ‘really’ being sincere,” your argument is already starting to break down. What does it mean for a piece of writing to be sincere but not “really” be sincere? I honestly just don’t know what you mean by that. (I want to understand! Tell me what you mean!)

The thing is, if we’re going to throw the words “sincere” and “ironic” around we have to agree on some basic definitions. You describe some of these titles as emotive or emotional. That description, I think, applies — but we have to keep in mind that “emotional” and “sincere” are not synonyms. I could say “I’m feeling nothing right now” and be totally sincere about it.

As always, xoxoxo and then some.

“What makes writing ‘sincerely’ even more delicious when perceived against postmodernism 1960–2000 is that it proposes to offer precisely what pomo said didn’t matter or couldn’t exist: direct communion with another coherent, expressive self, even truth by means of language.”

— Well, as long as your truth remains “little ‘t’ truth” and not “big ‘T’ truth” then I’m not sure there’s a problem for the “pomos.” And as long as your working with a more, say, communitarian understanding of “the self” as opposed to an atomistic one, then, again, I don’t think there’s much room for disagreement.

Anyway: Homogenizing postmodernists and lumping them together as you do, suggesting there is a coherent narrative and teleological account of their actions, is, in itself, a gesture “they” might perceive as a very violent, totalizing, and monologically reductionistic maneuver. All I’m saying is: It’s really hard to talk about postmodernists. Especially from what seems to be your metaphysical vantage point. Be careful.

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759 – 1767)

The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha (1605 – 1615)

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749)

By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept (1945)

Lolita, or the Confession of a White Widowed Male (1955)

(i’m taking liberties, i know)

i just ate leftover pizza for breakfast and i didn’t give any to my dogs although they desperately wanted some sitting by me looking so pathetic and now i am going to be late and slightly under-prepared for work

Thanks for the comment, Elisa! And, yes, I agree, definitions are needed. Although I think I have already been offering a definition of sincerity and its appearance in writing: that the text appear unmediated, or uncensored, or transparent, or unedited, etc.

I think the two dictionary definitions you offer might also work. Let’s try it out.

Tao Lin: you are a little bit happier than i am

Does that appear to be something Tao Lin genuinely believes? Does it proceed from genuine feelings? I think so, yes.

Now, when I say it doesn’t matter if Tao Lin really feels this way, I just mean literally that. We can write things that appear one way but that are not the way we genuinely feel. So maybe Tao Lin genuinely feels quite happy, even happier than me? But I don’t think that matters because poetry and fiction need not be true; it’s the projected appearance that matters.

So I think the New Sincerity is writing that prizes the appearance of genuineness that proceeds from genuine feelings, and it does so through particular literary devices.I agree that “emotional” and “sincere” are synonyms. That said, I think one reason why the NS focuses on emotions is because they are usually a sign of genuineness: “He couldn’t hide his feelings.” Dorothea Lasky, for instance, regularly creates in her work the effect that she has become emotionally overwhelmed, and is “directly” recording that emotional upswell in language. That she’s emoting directly onto the page. Of course that is entirely a rhetorical/formal effect, but it feels spontaneous, genuine, sincere.

Also, feeling nothing is a feeling. But what matters is the tone of that expression. Do I believe you when you say that? Again, I think this has become an issue in recent literature because it follows hard upon legions of writers, critics, and theorists who extolled the line that the self was fragmented and that language couldn’t communicate, etc. As well as legions of writers who prized irony—who used language to say the opposite of what they were literally saying.

I really do appreciate this conversation because I want to refine what I sense/mean. Indeed, my exchanges with you have been some of the most helpful in this regard.

xoxoxo back! Adam

I definitely agree that it’s a bad idea to homogenize, especially something as vast as pomo. (I’ve written before on why I even have my doubts as to whether pomo really is anything coherent.) But I also think one can generalize at times, and I think it’s safe to say that the general concept of pomo included the notion that language could not be used sincerely: that we were always saying other than what we meant, that the self was incoherent and fragmented, that language was always getting away from us in an endless play of signifiers, etc. Obviously any paper or book on this topic would have to do a much better job of nailing that down, but for now perhaps we can work with something like this? Though I appreciate nuance and clarification.

Thanks for your comment! Adam

Also, Elisa, I’ve been thinking more about the New Sincerity and the New Childishness, and I think they’re two separate things, although they strongly overlap at times. Acting childishly can be a good way to “appear sincere.” But one need not follow that strategy to get at sincerity. But one can also use childishness ironically—Ulrich Haarburste’s Novel of Roy Orbison in Clingfilm is a good example.

One can be childish and sincere, childish and ironic, sincere without being childish or ironic, and childish without being sincere or ironic. (“Without” there means without privileging it in the work.)

No doubt I’ll try writing more about this…

A

Thanks, that does help clarify! I still think *you are a little bit happier than i am* is largely an exercise in irony — in other words, my answer to the questions, “Does that appear to be something Tao Lin genuinely believes? Does it proceed from genuine feelings?” would be no (and I don’t care if he says yes!). I’ll try to blog about this soon so I can go into my reasons in a little more depth.

Excellent! I’ll look forward to that post. Perhaps I’ll respond by doing some readings of Lin that maybe demonstrate sincerity? Although I don’t want to make the issue of the NS’s existence depend entirely on Lin :)

Also, if someone else has a better account of all of this (all

of this!) then please chime in, because I would love to hear

it! (“2012: The year HTMLGIANT figured out contemporary lit.”)

I have to go to Michigan tomorrow but will try to follow the conversation here / in the Monday post. And I will put up Part 2 of WWTAWWTATNS this coming Monday morning.

Till then much love & thanks for reading & considering /discussing all of this,

Adam

enjoying these a lot

Maybe we should do it Lincoln-Douglas debate style…

Another way to put it is that what an artist intends to communicate in a work of art need not be what they are actually feeling/thinking. I can write a poem about the death of my dog, and make it appear genuine:

And I can write this despite the fact that my dog’s not dead. Because I have never owned one.

When my dog died, I could have instead written the following:

I plagiarized that poem (and retitled it). And it seems to me a “sincere expression” of grief over the loss of a pet.

Which of the two poems feels more sincere?

Which feels more hackneyed?

Which feels more New Sincere?

Thanks!

Thanks!

My friend Justin had a great idea: try to find titles that “seem New Sincere” and that are (much) older than 2005.

The Carver ones are the closest I’ve been able to find so far. (I am not suggesting Carver was NS!)

But when you say you can “make it appear genuine,” I’m not convinced — knowing that you are the “author” of that poem, it reads to me as ironic, not sincere or genuine. And that’s because I know you are educated and well-read and capable of speaking in higher, more complex registers. So when an A D Jameson or a Tao Lin writes a poem with very simple sentence structures and no capitalization and a childlike vocabulary, and publishes it in a title on Action Books or Fence, as opposed to on their Live Journal, the overall effect is ironic. The context matters. It’s like Jeff Koons selling Michael Jackson memorabilia as high art — there’s a difference between the way we read the Jeff Koons piece and the way we read a Hummel figurine at a garage sale. And it feels like maybe you’re not acknowledging that difference when you say that such and such Tao Lin poem is sincere. It’s more complicated than that, and you have to invoke irony to explain the full effect.

I still like the example from my blog: “A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People From Being a Burden on Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick” ;)

With respect to the question of defining “sincere” – ‘congruity between statements or displays and underlying motivations and, especially, self-understanding’ – , I think the blogicle clearly puts the calling of something sincere or insincere in a post-modern, ‘suspicious’ framework:

The question of ‘really being sincere’ is, from the get-go, irrelevant or, at least, circumvented, because the real interior of the communicating person — let’s say, poet or storyteller — is neither evident nor, perhaps, perfectly knowable from the outside.

I think that Adam means that what one has is the poem or story, not the naked, uncontroversial motivation and self-understanding of the writer – not the writer herself, as it were – , and (perhaps) others themselves are never perfectly accessible, anyway.

–or rather, one does ‘have’ the motivation of a writer, but seen darkly, through the glass of the world that is the condition for the possibility–the necessity–of multiple perspectives.

Put simply, one can’t know (in a strong sense of methodological distinction of ‘true’ from ‘false’ – a Euclidean or scientific sense) if someone is “sincere”, but one does know, as much (or little) as one knows oneself, whether one thinks another person – a writer, say – is “being sincere”. And there are ways – commonly known, part of the cultural toolkit of social competence – for communicators to signal — never completely unambiguously — that they’re really being sincere.

Adam’s systematic tentativity about someone else’s ‘sincerity’ isn’t a breaking-away from “sincerity” (to talk about something else, or, insincerely, only to pretend to talk about ‘sincerity’), as I understand him. It’s an explicit acknowledgement, an open intrication, of the epistemic opacity universal to perspective.

(Is there a post-modernist who doesn’t share – indeed, who doesn’t thematize – this tentativity?)

So, if someone tells you something, whether they’re confessing, or gossiping about other people, or making up a story, you don’t really know if they mean to cause the effects in you they do, but you do know if you think they meant to do that — you even know, if you care to guess, what you think their motivations were. From that, you ‘decide’, more or less tentatively, if you think they were being “sincere”.

–and if you know that you don’t know certainly the other person’s motivations for creating those effects, it doesn’t matter to your understanding, at some particular moment, whether they are ‘really being sincere’. Why would it?–if you understand that that’s not something you can know (in a strong sense of knowledge).

But if we can’t really know, inside this framework, aren’t all texts equally “sincere”?

Let me also suggest that “irony” is not the opposite of “sincerity”.

Intentional, artfully conscious irony is always both ‘sincere’ and ‘insincere’, truthful (‘I want you to believe me’) and dishonest (‘I know I don’t think what I’m saying is true’); that duality is inherent in deception, ειρωνεια.

Situational irony, dramatic irony, the incongruity of plans and outcomes, and so on — all the many things and relations that are reasonably called ‘ironic’ — … “sincerity” isn’t a parameter of judgement there, is it?

I mean that when Oedipus seeks the murderer of the former king, and he already knows who did it – he knows that he did it, and he knows that he killed his father and made a family with his mother, he knew before he did these things that he would do them, he knew who he was because Apollo told him — but he didn’t know what he knew . . . Oedipus’s “sincerity” isn’t at all an issue, is it? Had he just been a liar – ‘Yes, I recognized my father then… and I killed the bastard!’ – , well, the story wouldn’t have the power it does: an intimation that your discovery of yourself will be a surprise.

Criticizing an ironist for being insincere – as Plato’s Socrates is criticized – … that would be – it was then! – poetically just αμαρτια, ‘missing the mark’.

that’s a great example!

and then there’s “People Like That Are the Only People Here: Canonical Babbling in Peed Onk” from Lorrie Moore, the master of dry/heart-stabbing ‘humor’

Adam might scruple to say they’re not.

–but I think the premise of the question contradicts its (rhetorical) self-answer: since we can’t really know, we can’t say uncontroversially whether texts are “sincere”. Since we do know whether we think some particular writer is being manipulative, even maliciously devious, or deliberately transparent, we call that writer ‘insincere’ or ‘sincere’, respectively.

There are post-modernists who reason that epistemic opacity indicates that things-in-themselves are a smear or blur of identical whatness — that if we can’t know them perfectly, that all texts are equally “sincere” (or equally “insincere”). I think their reasoning is mistaken; the opacity is of knowingness, and requires no complete or precise predication of the thing which is by its definition incompletely, but not completely un-, ‘known’.

Think of this discernment in mercifully everyday terms: a friend tells you how much they like you, how they share your best interests. Well, you know something to some degree! You have reasons – imperfect – for thinking what you do about your friend’s assertion: they’re drunk, they feel guilty, they feel sorry for you, they really do like you, you’ve always been generous and they want to thank you, etc. etc. You don’t know with divine certainty, but you can be pretty sure, you can be absolutely sure and yet be surprised, you can be somewhat sure and live a thousand years and nothing ever contradicts your sense, and so on. Whether that person is not perfectly plain to you – well, pragmatically, it might be 99.9+% clear – , but you work, at any point, with some more or less mutable, more ore less fixed perspective.

Is that not like how you decide — if it’s important to your relationship to some particular writer — whether you think they’re really being sincere?

(–and they’re many texts, discerning whose “sincerity” would be laughably beside the point of their effects. Is Shakespeare “sincere”? Uh, . . .)

[…] Johannes on Jun.08, 2012, under Uncategorized Over at HTML Giant, AD Jameson has been blogging about “Sincerity” and “New Sincer… Why sincerity? What is its present value? My broad and still developing belief is that […]

enjoyed this post

i like bukowski’s titles

It Catches My Heart in Its Hands (1963)

Poems Written Before Jumping Out of an 8 story Window (1968)

The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Over the Hills (1969)

Me and Your Sometimes Love Poems (1972)

Play the Piano Drunk Like a Percussion Instrument Until the Fingers Begin to Bleed a Bit (1979)

You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense (1986)

What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire. (1999)

Sifting Through the Madness for the Word, the Line, the Way (2003)

i have a question: what happened to the old sincerity?

You know me, and you know I don’t write like that, sure. But what if I started writing like that (the first poem), and then kept writing like that for the rest of my life? Or what if I signed it with a different name?

Again, though, Elisa, and I can’t stress this enough, regardless of whether you read it as being ironic or sincere, there is still a formal aesthetic present that we can describe, and that is what interests me, and that is what I want to isolate and describe. You and I may find the NS, ultimately, ironic, but that doesn’t change the fact that Tao Lin uses certain devices, as opposed to the devices that, say, Virgina Konchan uses.

It seems to me your interest, so far, has been in determining what is the effect of the work. That is not my interest. I am concerned here and now with isolating and identifying the formal devices that produce a particular style or body of styles, inasmuch as that can be done.

That’s a good example of a title whose argumentative effect does depend on “looking” as sincere as possible for as long as possible. If you know that Swift is putting you on right away, the piece loses a lot of its satirical effect. And who knows? Maybe some contemporary NS writers are using NS techniques to do precisely the same thing.

But I don’t think the Swift example contains any of the NS aesthetic devices. It’s not rambly or “emotional,” for one thing (two things). It seems calculated, precise, analytical. The only thing in it that might “appear” NS is the diminutive “modest.”

Elisa, of course once an aesthetic is established, writers will be able to use it in various ways. One can use the NS aesthetic satirically and ironically. As I mentioned above, you seem focused on discussing the effects of the style in general. I think that’s wrong, because you should focus more on individual works, and not the entire style. (Saying that all NS writing ultimately reads ironically is, I think, an indefensible claim—and not unlike saying that “all Impressionists paintings produce the same effect,” or something like that.) You have to go work by work. Different NS writers will use the strategies to do different things. For me, I’m interested in the devices, the strategies (for now).

So maybe a particular Tao Lin piece or book is satirizing other NS writers? That would be an interesting claim. Having read all of his work, I don’t see it as having any one single goal or effect. Rather, Lin strikes me as an utter formalist who has been rigorously exploring a certain aesthetic, or small set of aesthetics, in a variety of ways. And that to me is a large portion of his artistry.

What motivated me to get started on all of this, we should recall, is that I wanted to dismiss criticisms of Lin by Josh Cohen and others that Lin’s work is artless and lacks artifice. Here’s a perfect example of someone thinking the work is “just sincere”:

http://www.bookforum.com/inprint/1703/6361

On the opposite side of the spectrum, you have something like this:

http://wewhoareabouttodie.com/2010/09/07/unedited-feelings-on-tao-lin-and-tao-lins-richard-yates/

Obviously something is going on. People are reacting to this writing as though it’s sincerity made flesh. Me, that’s not the reaction I have; I never read it and think, “Oh, now I have a window into Tao Lin’s soul,” or a window onto his private life. All I see is the style, and the form. And that’s all I want to describe.

I am not interested in surveying people’s responses to the work, seeing who thought it sincere, who thought it ironic. Again, the “really sincere / really ironic” angle is, I think, a dead end! (It’s Wimsatt & Beardsley’s Affective Fallacy.)

And before anyone says it, affect and effect are totally different things. An artist can design an artwork to have an intended effect, and its success as an artwork doesn’t necessarily depend on whether people really respond that way. So, for instance, a joke is intended to be funny. And if I write a joke and tell it to you, and you don’t laugh, that doesn’t mean the joke isn’t successful or well constructed. It might just be that you never laugh at jokes.

Cabin in the Woods is a horror film, and it is designed to scare some percentage of its audience. (It’s also intended to make viewers laugh.) And it remains a horror film even if you yourself weren’t scared be it. (Me, I found it terrifying, but I am easily scared by horror films.)

We know it’s a horror film not necessarily because of any particular effect it has on any particular viewer, but because it is constructed in a way that participates in a certain formal tradition—the horror film tradition. And then it goes about playing with those devices and forms and tradition in very particular ways.

So what interests me about Lin’s work, for example, and the NS in general, is how a body of shared aesthetic devices is growing that artists can then communally work with. What they do with it, and what any particular reader’s response to it is, is now what interests me.

Elisa, did you like Cabin in the Woods?

I was wondering if Bukowski might be some precedent here, in particular Play the Piano Drunk. Thanks, Tao!

Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say, 1992-3.

The best known work of visual art by Gillian Wearing, in the form of a cycle of photographs of people she approached at random on the street and gave a pen and blank sheet of paper and asked to write absolutely whatever they felt like writing. This is not just an appropriate title, but a good example of what NS stands for? I could be totally off.

Also,

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With: 1963-1995, by Tracey Emin,

although appropriate to a lesser extent, I think.

There are not a lot of examples of NS from visual art here, nor from Europe; just an observation.

‘Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say’, 1992-3 by Gillian Wearing.

This is Wearing’s best known work, which takes the form of a cycle of photographs. Each picture shows a different person who the artist approached at random on the street and gave a pen and blank sheet of paper and asked to write, and then hold up for display, absolutely whatever it was they felt like. If I am understanding NS somewhat correctly, this is a good example not only for it’s meandering title, but for its content, for the raw sincerity of strangers which it successfully unfettered.

Perhaps I might also suggest ‘Everyone I Have Ever Slept With: 1963-1995’ by Tracey Emin, although it’s considerably less apt than Wearing, methinks.

There aren’t very many examples of NS taken from visual art, nor from Europe; just an observation.

J.V. Foix, the Catalan poet (self-proclaimed “investigator of poetry”) 1893-1987, was known for his long titles which acted as surreal stories…although he was also know for an “ironic vision”

I ARRIVED IN THAT TOWN, EVERYONE GREETED ME AND I DIDN’T

KNOW A SOUL: WHEN I WAS ABOUT TO READ MY VERSES, THE

DEVIL, HIDING BEHIND A TREE, CALLED OUT TO ME

SARCASTICALLY AND FILLED MY HANDS WITH NEWSPAPER

CUTTINGS

AT THE ENTRANCE TO A SUBTERRANEAN STATION, TIED HAND AND

FOOT BY BEARDED CUSTOMS MEN, I SAW MARTA LEAVING IN A

FRONTIER TRAIN. I WANTED TO SMILE AT HER, BUT A MANY-HEADED

MILITIAMAN TOOK ME OFF WITH HIS MEN, AND SET FIRE TO THE

WOODS

A SICILIAN PILGRIM, THE VICTIM OF THREE BUDDHIST HEROIN

TRAFFICKERS, WATCHES NIGHT AND DAY OVER THE AQUARIA, AND

ASSAULTS THE WINGED INSECTS WITH AN ORCHID.

A ROSE WITH A DAGGER IN ITS BREAST

LEAPS, BLEEDING, OUT OF THE WINDOW.

Sincerity, to me, is synonymous with honesty. I just can’t separate

a deceitful artist with his/her work that is sincere exclusively by its own

devices. Artist intent matters to me and sometimes it hard to tell whether it’s sincere or not.

[…] Göransson penned a response (at Montevidayo) to my post “I am drinking gin & wrote about 18 long titles i randomly chose using wikipedia.” I read it right away and it seemed to me that Johannes wasn’t really replying to my […]

[…] Giant is wonderful, and AD Jameson writes about the New Sincerity which deserves a read, “I am drinking gin & wrote about 18 long titles i randomly chose using wikipedia.” Also see “What we talk about when we talk about the New […]

[…] 07 June: “I am drinking gin & wrote about 18 long titles i randomly chose using wikipedia” […]

[…] I’ve said repeatedly over at HG, sincerity and naivity in art are strategic effects. The Shaggs really couldn’t play their […]

[…] Over at HTML Giant, AD Jameson has been blogging about “Sincerity” and “New Sincer… […]