“Musil and Broch saddled the novel with enormous responsibilities. They saw it as the supreme intellectual synthesis, the last place where man could still question the world as a whole. They were convinced that the novel had tremendous synthetic power, that it could be poetry, fantasy, philosophy, aphorism, and essay all rolled into one. In his letters, Broch makes some profound observations on this issue. However, it seems to me that he obscures his own intentions by using the ill-chosen term “polyhistorical novel.” It was in fact Broch’s compatriot, Adalbert Stifter, a classic of Austrian prose, who created a truly polyhistorical novel in his Der Nachsommer [Indian Summer], published in 1857. The novel is famous: Nietzsche considered it to be one of the four greatest works of German literature. Today, it is unreadable. It’s packed with information about geology, botany, zoology, the crafts, painting, and architecture; but this gigantic, uplifting encyclopedia virtually leaves out man himself, and his situation. Precisely because it is polyhistorical, Der Nachsommer totally lacks what makes the novel special. This is not the case with Broch. On the contrary! He strove to discover “that which the novel alone can discover.” The specific object of what Broch liked to call “novelistic knowledge” is existence. In my view, the word “polyhistorical” must be defined as “that which brings together every device and every form of knowledge in order to shed light on existence.” Yes, I do feel close to such an approach.” – Milan Kundera in the Paris Review

“Musil and Broch saddled the novel with enormous responsibilities. They saw it as the supreme intellectual synthesis, the last place where man could still question the world as a whole. They were convinced that the novel had tremendous synthetic power, that it could be poetry, fantasy, philosophy, aphorism, and essay all rolled into one. In his letters, Broch makes some profound observations on this issue. However, it seems to me that he obscures his own intentions by using the ill-chosen term “polyhistorical novel.” It was in fact Broch’s compatriot, Adalbert Stifter, a classic of Austrian prose, who created a truly polyhistorical novel in his Der Nachsommer [Indian Summer], published in 1857. The novel is famous: Nietzsche considered it to be one of the four greatest works of German literature. Today, it is unreadable. It’s packed with information about geology, botany, zoology, the crafts, painting, and architecture; but this gigantic, uplifting encyclopedia virtually leaves out man himself, and his situation. Precisely because it is polyhistorical, Der Nachsommer totally lacks what makes the novel special. This is not the case with Broch. On the contrary! He strove to discover “that which the novel alone can discover.” The specific object of what Broch liked to call “novelistic knowledge” is existence. In my view, the word “polyhistorical” must be defined as “that which brings together every device and every form of knowledge in order to shed light on existence.” Yes, I do feel close to such an approach.” – Milan Kundera in the Paris Review

“On the other hand, I think Great Books should be taught and read—but there are certain subjects that are difficult to embrace at a young age, and certainly the impact of time is going to fall pretty flat. So this book,Goon Squad, is very much a response to the rereading of Proust, honestly. I thought, “How would you write about time now?” And technology plays a big part in In Search of Lost Time, which is really not much talked about. There is one part: He [Proust] looks up in the air and an airplane goes by and it is so shocking because it feels like such a 19th-century novel. It’s really not.” – Jennifer Egan, in the Morning News

“On the other hand, I think Great Books should be taught and read—but there are certain subjects that are difficult to embrace at a young age, and certainly the impact of time is going to fall pretty flat. So this book,Goon Squad, is very much a response to the rereading of Proust, honestly. I thought, “How would you write about time now?” And technology plays a big part in In Search of Lost Time, which is really not much talked about. There is one part: He [Proust] looks up in the air and an airplane goes by and it is so shocking because it feels like such a 19th-century novel. It’s really not.” – Jennifer Egan, in the Morning News

“I had that same relationship with Plath, actually. I think I was too caught up in her biography to give her poetry the attention and work it deserves. Also, my biggest love right now, the British Renaissance, was not a love of mine in undergrad. Not at all. It came later in graduate school. But now I can’t get enough of “Paradise Lost,” for example. No lie. It’s amazing. Frightening, really sexy, and incredibly dense yet completely readable like a novel.” – Erica Dawson, in The Black Telephone

“I had that same relationship with Plath, actually. I think I was too caught up in her biography to give her poetry the attention and work it deserves. Also, my biggest love right now, the British Renaissance, was not a love of mine in undergrad. Not at all. It came later in graduate school. But now I can’t get enough of “Paradise Lost,” for example. No lie. It’s amazing. Frightening, really sexy, and incredibly dense yet completely readable like a novel.” – Erica Dawson, in The Black Telephone

“Dialogue is a process and we are at the beginning. Looking back in history we now see that Christianity has been in dialogue since its inception. Jesus was a Jew. He spoke like a Jew, thought like a Jew and acted like a Jew. Christianity was at first seen as a Jewish sect. The person who brought it into the Greek world and initiated the first great dialogue was St. Paul. Then in the 13th century, when Aristotle was introduced into Europe, Aquinas initiated a dialogue that resulted in a Thomism that dominated Catholic theology until the Second Vatican Council. Now, even as we speak, Christianity is in the process of extracting itself from one culture and becoming incarnate in another. The new culture is deeply influenced by Asian religions and the work of dialogue is only the beginning. ” – Shusaku Endo in America

“Dialogue is a process and we are at the beginning. Looking back in history we now see that Christianity has been in dialogue since its inception. Jesus was a Jew. He spoke like a Jew, thought like a Jew and acted like a Jew. Christianity was at first seen as a Jewish sect. The person who brought it into the Greek world and initiated the first great dialogue was St. Paul. Then in the 13th century, when Aristotle was introduced into Europe, Aquinas initiated a dialogue that resulted in a Thomism that dominated Catholic theology until the Second Vatican Council. Now, even as we speak, Christianity is in the process of extracting itself from one culture and becoming incarnate in another. The new culture is deeply influenced by Asian religions and the work of dialogue is only the beginning. ” – Shusaku Endo in America

“When I write a story, I type a sentence and read it out loud. And then I change it, and read it out loud again. And then I write the next sentence, and I read it out loud, and I read the previous sentence out loud, and I change that. And this goes on for a while. The repetitions tend to come out of a desire for a musicality to the writing, which follows from the fact that I am reading it out loud as I am writing it.” – Matthew Simmons, in Dark Sky

“When I write a story, I type a sentence and read it out loud. And then I change it, and read it out loud again. And then I write the next sentence, and I read it out loud, and I read the previous sentence out loud, and I change that. And this goes on for a while. The repetitions tend to come out of a desire for a musicality to the writing, which follows from the fact that I am reading it out loud as I am writing it.” – Matthew Simmons, in Dark Sky

Erica Albright may be Erika Albright, depending on your Roman or Germanic tendencies, and these two people may or may not be one person, an actual living person who actually does normal warm blooded things like have a facebook account, or she is merely the invention of a screen writer whose agency is to represent the “common” folk, the morally clear dissenters of a would-be contemporary hero. “And I want you to know, from the bottom of my heart, that that won’t be true. It’ll be because you’re an asshole,” Erica says before leaving the supposed asshole. This took place over a beer, the best time to call someone an asshole. But all this is fiction, of course, a fiction that doesn’t seem to end when the film does; you see, the warm blood folk like you and me but maybe with more time created facebook accounts for Erica, so so many, that it ceases to be possible or important to know who the real one is. We live in a time where “real” is a disclaimer, almost a kind of warning. This isn’t anything new. Jesus has the most facebook, twitter, and myspace accounts, and let us not explode our heads pondering the ironic to earnest ratio. Hitler and Christopher Walken probably come in a close second and third. Erica’s dignified and morally minded dissent from our hero has propelled her into a modern Joan of Arc, each “like” the blue flame of a smart phone under the sheets checking for that final text. Zuckerberg’s “real” girlfriend, whom he was dating during the time implicated in the movie, is a Chinese-American med student, whose race was smartly passed over because nobody wants to see Joy Luck Club II: The Bitch is Back or something. Erica is much more suited to fill the role of the strong liberated American college girl. A quick image search for “Erica Albright” yields many pictures of similar looking girls, some of whom are the actress Rooney Mara, all of them fairly attractive, all supposedly, according to the proclamations on their linked blogs, the real Erica Albright. My favorite scene of hers (Mara’s) is her

Erica Albright may be Erika Albright, depending on your Roman or Germanic tendencies, and these two people may or may not be one person, an actual living person who actually does normal warm blooded things like have a facebook account, or she is merely the invention of a screen writer whose agency is to represent the “common” folk, the morally clear dissenters of a would-be contemporary hero. “And I want you to know, from the bottom of my heart, that that won’t be true. It’ll be because you’re an asshole,” Erica says before leaving the supposed asshole. This took place over a beer, the best time to call someone an asshole. But all this is fiction, of course, a fiction that doesn’t seem to end when the film does; you see, the warm blood folk like you and me but maybe with more time created facebook accounts for Erica, so so many, that it ceases to be possible or important to know who the real one is. We live in a time where “real” is a disclaimer, almost a kind of warning. This isn’t anything new. Jesus has the most facebook, twitter, and myspace accounts, and let us not explode our heads pondering the ironic to earnest ratio. Hitler and Christopher Walken probably come in a close second and third. Erica’s dignified and morally minded dissent from our hero has propelled her into a modern Joan of Arc, each “like” the blue flame of a smart phone under the sheets checking for that final text. Zuckerberg’s “real” girlfriend, whom he was dating during the time implicated in the movie, is a Chinese-American med student, whose race was smartly passed over because nobody wants to see Joy Luck Club II: The Bitch is Back or something. Erica is much more suited to fill the role of the strong liberated American college girl. A quick image search for “Erica Albright” yields many pictures of similar looking girls, some of whom are the actress Rooney Mara, all of them fairly attractive, all supposedly, according to the proclamations on their linked blogs, the real Erica Albright. My favorite scene of hers (Mara’s) is her

“I don’t believe I have a mission. Sometimes I really have a spiritual need to say something more general about the world, and sometimes something personal. I usually write for the individual reader–though I would like to have many such readers. There are some poets who write for people assembled in big rooms, so they can live through something collectively. I prefer my reader to take my poem and have a one-on-one relationship with it.” –

“I don’t believe I have a mission. Sometimes I really have a spiritual need to say something more general about the world, and sometimes something personal. I usually write for the individual reader–though I would like to have many such readers. There are some poets who write for people assembled in big rooms, so they can live through something collectively. I prefer my reader to take my poem and have a one-on-one relationship with it.” –  “Recently I was giving a talk, and someone asked if I would ever write a romance novel. It was a funny question. But then I thought, well, okay, maybe. I come from a different culture and it could work to my advantage or disadvantage. What I consider romantic may not necessarily be what other people consider romantic. I’ve lived in this culture long enough to test some of the hypotheses of what romance is to me on a few people, and it hasn’t worked out quite that well [laughs]. For example, in the context of Sierra Leone, romance could mean a woman cooking for a man and sending a dish to the man’s house as a sign of showing that she cares and that she loves the man. Whereas in the West if you ask some women to cook for you, they may think otherwise—they may think you see them as belonging to the kitchen and that sort of thing.” –

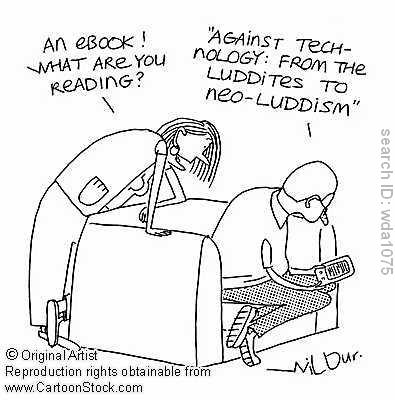

“Recently I was giving a talk, and someone asked if I would ever write a romance novel. It was a funny question. But then I thought, well, okay, maybe. I come from a different culture and it could work to my advantage or disadvantage. What I consider romantic may not necessarily be what other people consider romantic. I’ve lived in this culture long enough to test some of the hypotheses of what romance is to me on a few people, and it hasn’t worked out quite that well [laughs]. For example, in the context of Sierra Leone, romance could mean a woman cooking for a man and sending a dish to the man’s house as a sign of showing that she cares and that she loves the man. Whereas in the West if you ask some women to cook for you, they may think otherwise—they may think you see them as belonging to the kitchen and that sort of thing.” – “i don’t think that the internet has changed the way i write, necessarily, but it certainly has opened up a new set of possibilities for myself and other writers in terms of finding an audience, and i think that has had a pretty profound impact. when i started writing, there were very few feasible options in terms of publishing work, and even then, the feasibility was questionable. there was also a predictability – i wasn’t aware, then, of journals like conjunctions or grand street, and everything else was just too…agrarian. every lit journal i was exposed to was named after a tree, or an antique milliner’s tool, or something having to do with the ocean.” –

“i don’t think that the internet has changed the way i write, necessarily, but it certainly has opened up a new set of possibilities for myself and other writers in terms of finding an audience, and i think that has had a pretty profound impact. when i started writing, there were very few feasible options in terms of publishing work, and even then, the feasibility was questionable. there was also a predictability – i wasn’t aware, then, of journals like conjunctions or grand street, and everything else was just too…agrarian. every lit journal i was exposed to was named after a tree, or an antique milliner’s tool, or something having to do with the ocean.” –  “I found out it is hard to talk seriously about anything to the media. Recently they filmed The Human War to be made into a movie. The movie will be out next year sometime, I don’t know when or where it will appear. I had several interviews with major media outlets, like newspapers, college newspapers, and the local news. I got asked for simple, little questions that meant nothing. At one point during the filming, one of the directors asked me to talk to an actor about a character, I mentioned Plato and everyone got weirded out. It is strange, society wants authors, authors who know things, society might even want philosophers, not sure. But they don’t want us to know things in public in front of everyone. This is probably what many conservatives dislike, that there are people in society that know things. Most people are scared of people who know things and are also scared of those things they know. I probably wouldn’t mention Sartre or Nietzsche or Richard Wright, I wouldn’t mention anything. I would say, “ROAD TRIP NOVEL” “MICHAEL CERA” “CHINESE” “LOOKING FOR ONE SELF.” They would be attracted to those words. I would be saying those words and phrases, thinking in my head, “These words mean nothing.” But they wouldn’t, those words would mean a million wonderful money making things.” –

“I found out it is hard to talk seriously about anything to the media. Recently they filmed The Human War to be made into a movie. The movie will be out next year sometime, I don’t know when or where it will appear. I had several interviews with major media outlets, like newspapers, college newspapers, and the local news. I got asked for simple, little questions that meant nothing. At one point during the filming, one of the directors asked me to talk to an actor about a character, I mentioned Plato and everyone got weirded out. It is strange, society wants authors, authors who know things, society might even want philosophers, not sure. But they don’t want us to know things in public in front of everyone. This is probably what many conservatives dislike, that there are people in society that know things. Most people are scared of people who know things and are also scared of those things they know. I probably wouldn’t mention Sartre or Nietzsche or Richard Wright, I wouldn’t mention anything. I would say, “ROAD TRIP NOVEL” “MICHAEL CERA” “CHINESE” “LOOKING FOR ONE SELF.” They would be attracted to those words. I would be saying those words and phrases, thinking in my head, “These words mean nothing.” But they wouldn’t, those words would mean a million wonderful money making things.” –