- Shattered clock of memoir flashes. Thinking Abigail Thomas, John Edgar Wideman (in Harper’s or some mag like Harper’s a while back), Baudelaire, Between Parentheses, fuck I don’t know. Calling for flash nonfiction collection authors.

- The cover has a guy holding tiny baby chicks, as you can surmise. The chicks look like clay or bewildered paper balls.

- The real angling or net fishing is memory.

- Can you recall 5 stories from when you were age 10, maybe 5 interactions with dogs? Neither can I. Where did they collapse?

- Every flash, all 100, is 100 words. That’s called a drabble in fiction. Not exactly Oulipo but it has an effect, like a painting of a vulture in a mirror. Aesthetic restraints lead to increased creativity (and technique), not decreased. Perec taught us the wanderer can own the wall.

- Language leads on like a forehead, and seems to fulfill at time, the writer.

- I sense a cobweb fatigue with pretentiousness. You can feel a jacket being shucked and thrown crumpled to the floor.

- Writer asks, wonders, “Who was this Jack?”

- Shame, for example. A drowsing duck inside the chest cavity.

- My favorite line: I was wooing a Kansas City woman. Very Chinquee, in its direct way.

- I also enjoyed, “She died from alcohol, but nobody ever saw her take a drink.” READ MORE >

Sportin’ Jack by Paul Strohm 28.5 Points

January 28th, 2014 / 3:46 pm

25 Points: Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg

by John Gosslee

Rain Mountain Press, 2013

60 pages / $15.00 buy from Rain Mountain Press

1. Split-screen madness

2. Piano-playing, the keys turned to pills

3. A kiss on a grimy elevator floor

4. The interior of the exterior of a shut door

5. An angel with her arms torn off

6. Rejection, acceptance, rejection

7. Illustrations by Yumi Sakugawa, trees in a forest, pachyderms inside the breadth of a bird’s chest

8. Flashmobs, tornados, claws and urninals

9. An all-out assault on the status quo

10. A baker’s dozen of streets and silence mingled with the rattle of dead claws on stony ground READ MORE >

January 28th, 2014 / 3:12 pm

***

are you a “boy writer” ??

one of those who “remind us of how great it is to be alive…”

click here

BREAKUP TIME

10 Reasons Why The Knicks J.R. Smith Is Like The Novelist Norman Mailer

My favorite NBA player, Larry Johnson, had a gold front tooth, yelled at the ball during free throws, once told an interviewer that his diet consisted of soda and candy (imagine reading this as a teenager) and had a series of TV commercials where he transformed into his alter-ego: a gray-wig wearing, puffy flower dress clad, narrow vintage glasses wearing, “Grandmama.” I fondly remember wearing his replica jersey (the very first of these ever for sale) several sizes too large, more dress than jersey.

Boys Who Kill: Kevin Khatchadourian

The final Boys Who Kill for the time being brings the spotlight to Kevin Khatchadourian. On 10 April 1999, ten days prior to Dylan and Eric’s premiere of NBK, Kevin killed his daddy and his sister before going to school and murdering seven students, one English teacher, and one janitor in the gym.

Growing up, Kevin’s two favorite words, according to his mommy, were “Idonlikedat” and “dumb.” Whether it was his mommy’s milk, his mommy’s cooking, his mommy in general, music, or cartoons, Kevin’s would probably be displeased by it. Although, there are some things that Kevin does like, like computer viruses and Robin Hood. Both Robin Hood and computer viruses attack targets that possess plenty of materials. Robin Hood deprives rich people of their things and computer viruses deprive computers of their ability to preserve their multitude of files and functions.

Kevin’s granddaddy and grandmommy maintain a motto: “Materials are everything.” The granddaddy and grandmommy fill their lives by doing things. They install water softeners and purchase first-rate 1000-dollar speakers, even though they don’t really like music all that much. As for Kevin, his mommy says that he “was never one to deceive himself that, by merely filling it, he was putting his time to productive use.” While 99 percent of people spend their Saturday afternoons doing something, like speculating on what they intend to do that night or checking their social media feeds, Kevin is “doing nothing but reviling every second of every minute of his.” With a tough tummy, Kevin can do what the phony baloneys can’t: “face the void.”

Simone Weil has a similar perspective on life. For the French ascetic, nothingness is truthfulness since it has to do with God. “We can only know one thing about God: that he is what we are not,” says Simone in her notebooks. God isn’t composed of matter nor is he quantifiable. Unlike humans, there is no corporeal limit to God. He is infinite. Humans are a sham. They use their days trying to satiate various desires (hunger, thirst, xxx, and so on) even though these hankerings can never be permanently filled because human beings are really just one giant hole. As Simone declares, “Human life is impossible.” Simone and Kevin each confront the hopelessness of fulfillment in a material and fleshy existence. They each effect divinity through destruction — Simone destroys herself and Kevin destroy the things and people around him. READ MORE >

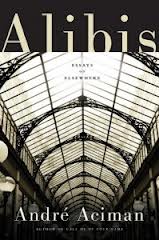

Yearning For Elsewhere: André Aciman’s Alibis

Alibis: Essays on Elsewhere

Alibis: Essays on Elsewhere

by André Aciman

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011

208 pages / Buy from Amazon

In his 2012 collection Alibis: Essays on Elsewhere, André Aciman explores the elsewheres of his life. He contemplates the places he’s lived and traveled to—Cambridge, Rome, Alexandria, Venice, and New York—and ruminates about what his life was like there. Except Aciman isn’t interested in actuality. Throughout this collection, he pursues an imagined past. It’s a touching, at times, fusty perspective where the “what was perhaps and might have been has more meaning than what just is.” It’s the perspective of a man who’s read too many books.

Aciman is reflective in an exquisitely literary way. He calls upon his beloved books and authors to define his experiences. Venice is understood by way of Thomas Mann. Tuscany is seen through the lens of Machiavelli’s letters. There’s “De Quincey’s London, Browning’s Florence, [and] Camus’s Oran,” not to mention Monet’s Bordighera, Virgil’s Rome, and Lawrence Durrell’s vanished Alexandria. This mix of high culture and Old World geography makes Aciman’s writing quite pleasurable. It’s hard not to be charmed by descriptions of Italian farmhouses and unsalted Tuscan bread interwoven with references to Dante. Simultaneously, the constant invocation of canonical literature grows moldy and, over time, seems like an extremely fancy crutch, as though Aciman is unable to experience the world without first quoting Proust and La Fayette.

It’s a delicate snare, one most readers can relate to. As we learn about the world through books and movies, we want to visit that world. Who wouldn’t, after reading Benjamin, Balzac, and Baudelaire, want that Paris over the drab Paris of today—a Paris we know nothing about? The elsewheres Aciman longs for are mirages, and he admits it. But they’re such beautiful mirages it’s easy to believe they’re realer than what goes on outside his hotel room window.

Aciman’s elsewheres are geographically and temporally distant from his present writerly position in “a cork-lined room.” Yet it is only here, sealed away in this room, removed from the hubbub and uproar of regular life, that Aciman’s elsewheres can exist. In “Intimacy,” one of the longer and strongest essays in the collection, he recalls his teenage days living with his mother on Via Clelia, a working-class street in Rome. Aciman and his family are exiles. They escaped Egypt in 1965. And after three years in Italy, they’ll move to America, a country that even decades later Aciman does not consider home. “Home,” he writes in a later essay, “is all together elsewhere.”

When Aciman revisits Via Clelia many years later, he’s tense with anticipation. He wishes for something thrilling to happen, for something to pop out and scream, Remember me? “But nothing happened. I was, as I always am during such moments, numb to the experience.” As it turns out, the old street where he used to live is just that, an old street. The barbershop and plumber’s storefront are gone but the printer’s shop remains. Via Clelia means nothing more or less than it always has. And that’s no good. During the present moments of his revisiting, Aciman’s anticipation and memories are squandered by the “numbness” he inevitably feels, a numbness frequently encountered whenever he’s confronted by the present. Fortunately, what we botch in life, we fix with art.

“It is the craft that makes life meaningful,” Aciman claims, “not the life itself.” This claim is repeated throughout Alibis and in his earlier books as well. Aciman finds meaning not in the moment, but in his memory of the moment, a memory that’s envisioned only long afterward, in that cork-lined room. It’s a claim that sets art up against life, a false dichotomy to be sure, but one that over the course of Aciman’s writing career has calcified into truth.

While analyzing Proust, Aciman describes a “literary time filter” that coats the world. In other essays, this “filter” is called an “illusory film”, “happy film”, or just plain “film.” It’s the façade of art, of artifice, of craft, which makes our past experiences more pleasing, sparkling, and grand, because it allows us to grasp the scintillating details and crystalline moments that are apparent only when we look back, details and moments that, quite naturally, are created by the intensity of our looking back. Aciman writes, “it is not the things we long for that we love; it is longing itself—just as it is not what we remember but remembrance itself that we love.” In eulogizing his past lives, Aciman cherishes not what has vanished or died, but the eulogy itself.

This is an incredibly literary take on life. At times it feels like too much. Aciman values the inventions of memory, where everything glows with the amber light of nostalgia and the spellbound evenings are seeped in melancholy blue, rather than what he quotes Proust as calling the “tyrannie du particulier, the tyranny of [the] day-to-day.” Aciman is entirely unable to enjoy the present moment, the day-to-day-ness of life, with its ephemeral joys and nonstop micro-disasters. The numbness he feels when faced with the immediacy of every passing moment can only be overcome through imaginative, highly referential reflection. “Even the experience of numbness,” he writes, “when traced on paper, acquires a resigned and disenchanted grace, a melancholy cadence that seems at once intimate and aroused compared with the original blah.” It’s this blah that Aciman believes the artist must do everything to defy.

January 27th, 2014 / 10:00 am

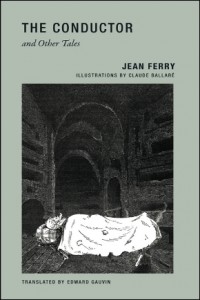

Review of The Conductor and Other Tales by Jean Ferry

The Conductor and Other Tales

The Conductor and Other Tales

by Jean Ferry

Wakefield Press, Nov 2013

176 pages / $13.95 Buy from Wakefield Press or Amazon

The biggest initial draw to this neglected collection of stories by avant-gardist Jean Ferry is his associations with other big names in French cinema and literature. Names like Buñuel, Carné, Malle, and Breton get dropped through the introductory materials to this edition, the first of his works to be fully published in English. Despite all these associations, the ultimate sensation one gets after reading this work, Ferry’s only collection of fiction, is that he’s not so easily lumped in with the surrealist or pataphysic movements that attempted to swallow him into their pigeonholes. Instead, as translator Edward Gauvin states in his introduction, “Ferry is the exception to every movement he’s been in,” a claim that ironically puts him further in line with the ideals of pataphysics .

The easiest way I can understand pataphysics is to say it’s the layer outside of metaphysics. Seeing as metaphysics is already shaky ground for thought systems, how does one breach the pataphysical level? Ferry’s method, in the handful of stories that best align themselves with this short-lived tradition, is to introduce a story very simply and unassumingly. The story then leads the reader subtly into abstract territory where one can infer a number of metaphors throughout the narration, ones that give the text its weight, just like any other well-executed traditional literary text. But what Ferry does is extends the metaphor further, going off into a tangent that speeds like a rocket, flying through incidents and ideologies it has no time to explain, but only enough to introduce in passing, making the end result of each of these bite sized stories, when looking back over them, akin to a godly perspective, where earlier particulars lose their distinctions.

The etymology of the term avant-garde derives from the group of soldiers sent into the battlefield earliest to scope out the situation. The job requires simultaneous sensitivities to caution, intuition, timeliness, and luck. Ferry’s take seems to be to speedily pull the avant-garde as far as he could take it, to sprint into the most vulnerable area of the form and celebrate it unabashedly. Instead of creeping around the bushes and trying to figure out the terrain, Ferry runs full speed through the deathly silent tension of a potential warzone, using luck as his only strategy. In this way Ferry doesn’t have time to go back and worry about if the path his narrative took may have been the wrong one; he doesn’t give himself that luxury. The intention is to go somewhere far beyond the point where normal beyond seekers are already going.

The first story, “Notice,” begins with a meta narrative of the collection, about the uncertainty of its publication, let alone shelf life. Instead of being stuck in worry and using that worry to craft embarrassing or tryhard lines wrought with uncertainty, Ferry storms through, forgetting the topic of his manuscript, and instead turns attention to the adventures of the desk drawer it’s housed in, following it all the way to its destruction only a couple of sentences later, where he returns to the manuscript papers as they are used to stuff a package on its way to Africa, making sure to note along the way that “none of this is implausible.” His manuscript is found, recorded into a Dictaphone, and translated into an esoteric African language. Red ants eat the manuscript, and the African tribe for which the manuscript was translated eventually goes extinct, aside from one member who finds the Dictaphone, and becomes the sole audience for this book. Ferry ends the tale, “I write for that black man.”

Although ‘Notice’ highlights Ferry’s methods, it neglects the themes that frequent this collection, the most prominent of which is fatigue. In what I think to be the best story in the collection, “Traveler with Luggage,” fatigue infects the mind that’s recovering from a mental breakdown to not only weigh it down like an anchor, but to set up sporadic snares for it to get trapped in. It seems that to Ferry, exhaustion and its resulting laziness is the greatest hurdle humanity has to overcome, and our light treatment of it results from our inability to understand its truly horrific nature. The veneer of comfort in leisure seamlessly morphs into insanity, and by the time it’s understood, one has “neither willpower, nor the will to have willpower.” For the creative narrator of this story, when stuck in such a predicament, one where laziness dismisses the need to be creative, only to replace it with nothingness, life itself takes on an unreal and unwelcoming tinge. “It was the most abominable dream I’d ever had, and it was no dream.”

“The Conductor” is the most polished piece of fiction in the entire collection, and best shows off Ferry’s skills in allegorical creation and pataphisical method. The person that the conductor addresses from the beginning, which could have been you, the reader, leaves at one point, but the conductor continues speaking, announcing, “believe me, we sure are making tracks.” What extending metaphors, storylines, and other forms beyond their limits like this does is allows us to illuminate the substance of the metaphor and everything around it, and get far enough away from it so that perhaps we can see the full picture of that substance, perhaps to check if we may have missed something inherent to it.

This small yet potent collection has too much to discuss in one brief review. Stories like “Kafka, or ‘The Secret Society,’” “My Aquarium,” “On the Frontiers of Plaster (A Few Notes on Sleep)”, and “Childhood Memories” all have a uniqueness that makes this book highly worthwhile. The illustrations by Claude Ballaré that appear before each story are a very welcome complement that add to the dark Romantic feel of the stories. For fans of quirky, bleak, and short French fiction from the post-surrealist era, this book is a new must have.

January 27th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Advice on How to Deliver a Kick Ass Poetry Reading

*****

[ …people keep coming up to me and saying things like “Rauan, I’m a brilliant writer but I don’t do well in front of an audience. Help me, Please…”

….and so, because, well, I just can’t not help people (it’s my calling, god damnit) I’ve spent weeks in my lab cooking up some wisdom for all you brilliant fucking writers… so, here, enjoy ]

*****

1) Less is more

2) Just be yourself. Especially if you’re an asshole, then totally be yourself because audiences love assholes. But if you’re boring then do not be yourself. Absolutely, do not be yourself. (remember, it’s a show, man. yeah, it’s a show). (sigh).

3) Be in love with the sound of your voice. Fuck #1 (“More is more.” … “and more…and more…and more…”).. Really, just read and read and just keep on reading. If you see people yawning, don’t worry, people are like dogs, they yawn when they’re learning something new and incredible. Just read. And read. And read.

4) Grab your dick or cunt a lot, point at it a lot, dance around the stage, hopping up and down, howling and moaning like a monkey– but remember, the whole time, to keep your dick or cunt dead center in the audience’s eye. This works great in Brooklyn. And by extension then (of course) everywhere else.

5) After every 3rd or 4th poem pause for a few moments (I mean drag it out…milk the moment) and then confide, to the dying audience, off-hand and smug as you can, that “yes, indeed, that was a nod to Charles Simic.” (Also, bring a bottle with you and in the middle of yr reading sit down and command the audience (yes, they love taking orders) to sit in a circle around you…

…And then everyone should just make out because, making out is the only reason anyone shows up at little shindig Poetry Readings anyways. Blah, blah…) …stare into poetry’s soul… blah, blah

6) Sail mumbling autistic through the reading portion of the evening (no biggie, really) and on, gloriously, into the Q & A where you can then triumphantly and whiningly bitch about any negative reviews you’ve received. Don’t answer their questions of course. Just bitch.

7) Drink lots of water beforehand and then sail out over the audience like a God and piss on them. (for added effect eat lots of asparagus). (…huh? … I used the word “sail” twice here?? Well, sue me god damn it).

***

and, as always, glad I could help

POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#12)

Russell Jaffe runs the Strange Cage reading series in Iowa City and his website is russelljaffeusa.com

untitled from STUMBLE X THE AIR STASIS BREATH

by

Russell Jaffe

I wrote the untitled poems in STUMBLE X THE AIR STASIS BREATH in winter. I tried hard to do a minimalist take on poetry as a lifelong proud maximalist. Now that chap-sized collection is a part of a bigger as-yet-unpublished manuscript called LOVER TO and is retitled INTROVERT TO. Everything you know is wrong.

STASIS BREATH in winter. I tried hard to do a minimalist take on poetry as a lifelong proud maximalist. Now that chap-sized collection is a part of a bigger as-yet-unpublished manuscript called LOVER TO and is retitled INTROVERT TO. Everything you know is wrong.

![]()

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!

January 25th, 2014 / 3:36 pm